CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 10, November 2012

544

AFRICA

The association of LQT with an elevated LVEDP (at a normal

LVEF – frequently defined as

>

45% ,

and used for the purpose

of this study) is striking. Diastolic dysfunction is a relatively new

concept when compared with LVEF. The commonest cause of

diastolic dysfunction is hypertensive heart disease. Often these

patients have thicker, stiffened left ventricles with good systolic

function, but impaired relaxation and compliance. Again, exactly

how diastolic dysfunction in IHD patients is associated with

QT prolongation remains unknown, but recently an association

was found between down-regulation of the hERG gene and QT

prolongation in rats with cardiac hypertrophy.

34

Ion-channels are embedded in a phospholipid bi-layer

primarily composed of cholesterol esters. Both congenital

LQTS and familial hypercholesterolaemia are more common

in South Africans of European descent. Co-segregation of

ion-channel disease and hypercholesterolaemia has not yet

been described in humans, but in Langendorff-perfused rabbit

hearts, hyperlipidaemia led to significant QT prolongation

compared with normocholesterolaemia, which can be reversed

by administering simvastatin.

35

Study limitations

This single-centre study in a state hospital setting may be prone

to selection bias due to the fact that patients were enrolled only

during rotations of the authors collecting the data through the

coronary care unit. However, all eligible patients were enrolled

during these intervals, leading us to believe that the cohort was

truly representative.

More than 80% of the studied population were of mixed racial

ancestry. One should therefore be careful to draw conclusions

about race and QT prolongation.

Prescribed medications were not checked and these may well

have prolonged the QT interval after discharge. However, this

study addressed the relationship between QTc prior to coronary

angiography and mortality at six months.

The effects of coronary revascularisation on QTc were also not

investigated but it was assumed that significant coronary stenosis

would have been treated appropriately by the interventional

cardiologist. Mortality in the LQT cohort remained high

regardless of coronary revascularisation. Follow up was relatively

short owing to the vast extent of the geographical catchment area

of the hospital.

Genetic screening was also not performed on the study

patients. Diastolic pressure was used as an indicator of diastolic

function; however, echocardiographic parameters of diastolic

function were not assessed.

Conclusion

This is the first description of LQTc in a cohort of IHD patients

in a South African setting. The study confirms that QTc, which

can be determined by a simple, non-invasive, inexpensive

method, is an index of subsequent sudden death in patients who

undergo coronary angiography for suspected IHD.

QTc prolongation before coronary angiography is also a

reflection of systolic and diastolic dysfunction (in the context

of normal systolic function) of the left ventricle, both of which

are independent predictors of mortality rate. Furthermore, LQTc

correlates with hypercholesterolaemia and a negative family

history of IHD.

We are grateful to Khetha Majola and Innocentia Louw for helping with data

capturing, Prof Daan Nel of the Centre for Statistical Consultation (CSC),

Stellenbosch University, for the statistical analysis, and the Harry Crossley

Foundation for generous financial assistance. Elizabeth Schaafsma and Pearl

Fredericks were of assistance in data collection and establishment of an

electronic database.

References

1.

Reardon M, Malik M. QT interval change with age in an overtly healthy

older population.

Clin Cardiol

1996;

19

: 949–952.

2.

Beyerbach DM, Kovacs RJ, Dmitrienko AA. Heart rate-corrected QT

interval in men increases during winter months.

Heart Rhythm

2007;

4

: 277–281.

3.

Molnar J, Zhang F, Weiss J,

et al

.

Diurnal pattern of QTc interval: how

long is prolonged? Possible relation to circadian triggers of cardiovas-

cular events.

J Am Coll Cardiol

1996;

27

: 76–83.

4.

Kautzner J. QT interval measurements.

Cardiac Electrophysiol Rev

2002;

6

: 273–277.

5.

Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W. QT interval: how to measure it and

what is “normal”.

J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol

2006;

17

: 333–336.

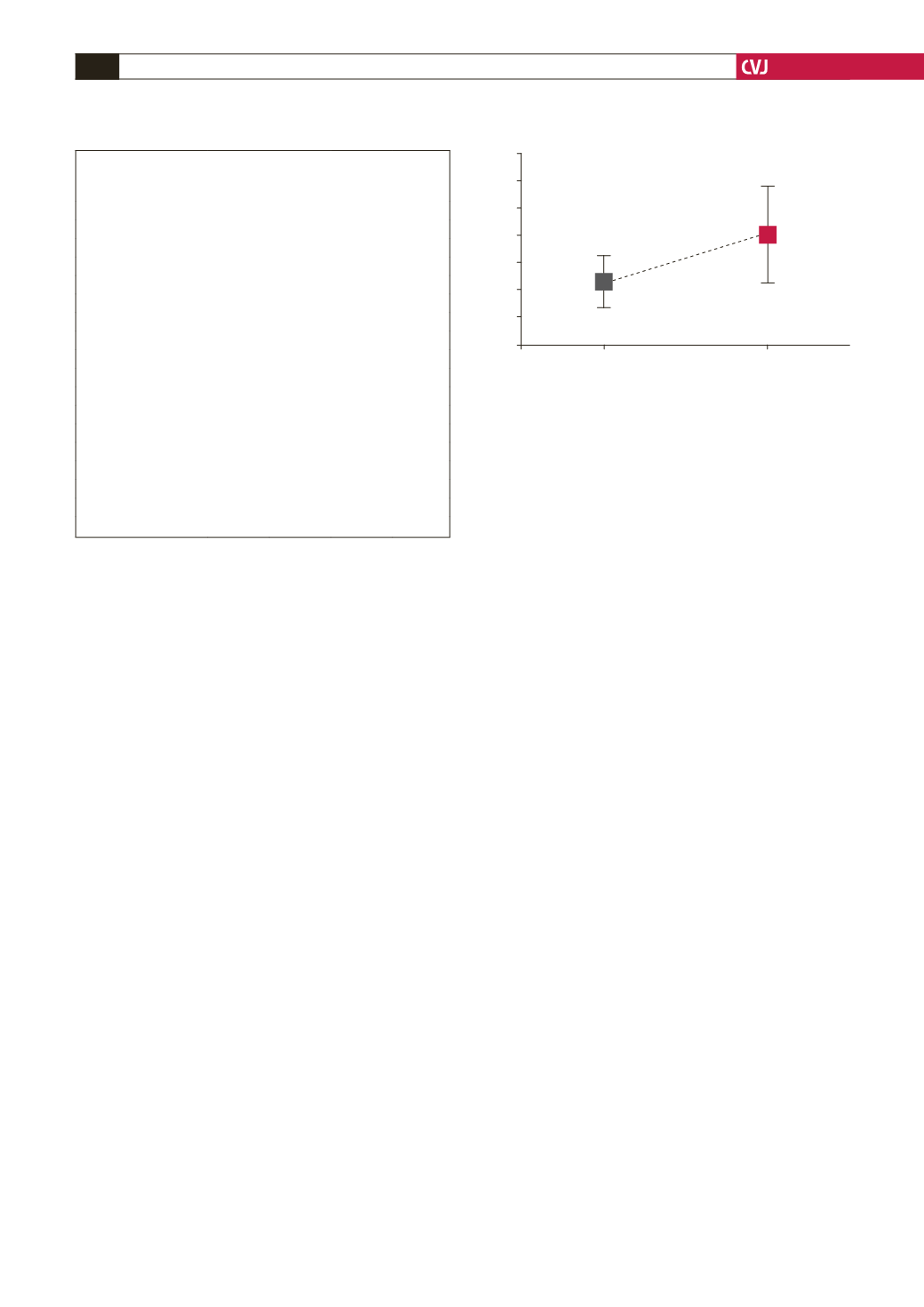

Fig. 5. Mean total serum cholesterol versus QTc interval

for NQTc and LQTc groups of patients.

6.0

5.8

5.6

5.4

5.2

5.0

4.8

4.6

NQTc

LQTc

QTc interval

Total serum cholesterol (mmol/l)

p

=

0.0355

Bar = 95% CI

TABLE 1. ASSOCIATION BETWEEN LQTc AND

NQTc GROUPS OF PATIENTSWITH REGARD

TO MAJOR RISK FACTORS FOR IHD

Risk factor present

Yes,

n

(%)

No,

n

(%)

Total,

n p

-

value

Diabetes mellitus

NQTc

62 (29)

149 (71)

211

0.54

LQTc

29 (33)

59 (67)

88

Total

n

91

208

299

Smoking

NQTc

116 (56)

92 (44)

208

0.19

LQTc

55 (64)

31 (36)

86

Total

n

171

123

294

Hypertension

NQTc

157 (74)

55 (26)

212

0.23

LQTc

70 (80)

17 (20)

87

Total

n

227

72

299

Family history

NQTc

74 (36)

134 (64)

208

0.045*

LQTc

21 (24)

67 (76)

88

Total

n

95

201

296

*

Statistically significant association.