CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 2, March 2013

20

AFRICA

warfarin.

22

In addition, drugs such as NSAIDs that possess

antiplatelet activity can produce additive anticoagulant effects on

concurrent administration with warfarin.

23

Broad-spectrum antibacterial agents, through their effects

on the vitamin K-producing gut flora, increase the effect

of warfarin.

24

Competitive substrates, inducers and inhibitors

of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 can alter warfarin plasma levels,

with consequent alterations in INR.

25

Therefore studies on

utilisation and responses of warfarin in different patient groups

are important to assess the causes of differences in its clinical

response in a specific environment.

In South Africa, primary healthcare anticoagulation clinics

play an essential role in warfarin therapy. These clinics are

responsible for the education, optimisation and maintenance

of anticoagulant therapy in referred patients. The initiation

of anticoagulation is usually performed by the referring

doctor following appropriate diagnosis and indications. The

anticoagulant clinics are responsible for ensuring there are no

contraindications to warfarin therapy (especially the presence of

severe bleeding, first and third trimester pregnancy, and severe

hepatic disorders) and ascertaining compliance to therapy.

The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate

warfarin utilisation in two primary-care anticoagulation clinics

in Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa. The study aimed at

retrospective assessment of INR monitoring with consideration

of possible influences of co-medication on therapy.

Methods

A retrospective study was undertaken of all warfarin-related

prescriptions in the warfarin clinics of Wesfleur and Gugulethu

hospitals, covering a 12-month period between June 2008 and

May 2009. Wesfleur Hospital is located in Atlantis, an area

under the West Coast district municipality with a population

of about 140 000 people, the majority being Coloured [the

race classification was based on the national census categories,

and described as black (Africans), Coloured, Indian and

white]. It is a level-two facility which sees an average of

13 000 patients monthly. It runs a warfarin clinic every Friday,

managed by a doctor and supported by specialist physicians at

New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town, for referrals.

Gugulethu Hospital is situated in the highly populated

Gugulethu Township in the City of Cape Town municipality, and

is inhabited primarily by blacks. The hospital takes care of about

6 800 patients per month. The warfarin clinic is mostly managed

by a nursing sister or staff nurse, who contacts a doctor if the

patient’s INR results are abnormal.

Data extracted from the patient folders included age,

gender, race, weight, address, concurrent chronic illnesses and

medication, INR history (monthly INR levels measured in

the 12-month period of the study) and indication for warfarin

therapy. For the purpose of this study, a cut-off INR level of 3.5

was chosen. Patients above this limit have an increased risk of

toxicity, as discussed above. Patients were assigned to the INR >

3.5 group if they had one or more INR levels above 3.5 during

the course of the study.

Medications taken concurrently were pre-classified as

potentially relevant or non-relevant for drug–drug interactions

with warfarin using the South African Medicines Formulary

(SAMF). A list of drugs taken concurrently that could result in

drug–drug interactions was compiled.

Ethics approval for the project was obtained from the Health

Research Ethics Committee of the University of Stellenbosch,

and Wesfleur and Gugulethu Hospital managements approved

this project.

MS Excel was used to capture the data and STATISTICA

version 8 (data analysis software system,

www.statsoft.com)(StatSoft Inc, 2008) was used for data analysis. Summary

statistics was used to describe the variables. The Chi-square test

was used for statistical comparison between groups. A

p

-value

<

0.05 represented statistical significance in hypothesis testing.

Results

A total of 111 patient folders were retrieved and qualified

for this study after the exclusion of eight (four from each

hospital) due to incomplete data. The demographic variables

are summarised in Table 1. The Wesfleur Hospital had more

patients (76) on anticoagulant therapy than Gugulethu (35). The

racial distribution of the patients reflected the demography of

the inhabitants in the hospital locations; 88.1% of the patients

in Wesfleur were Coloured while all patients from Gugulethu

were black.

There was a significant variation in INR records in both

hospitals. While none of the patient records showed an INR

less than 2, over a third of the patients (32.2%) had at least one

record of INR greater than 3.5 in Gugulethu Hospital, compared

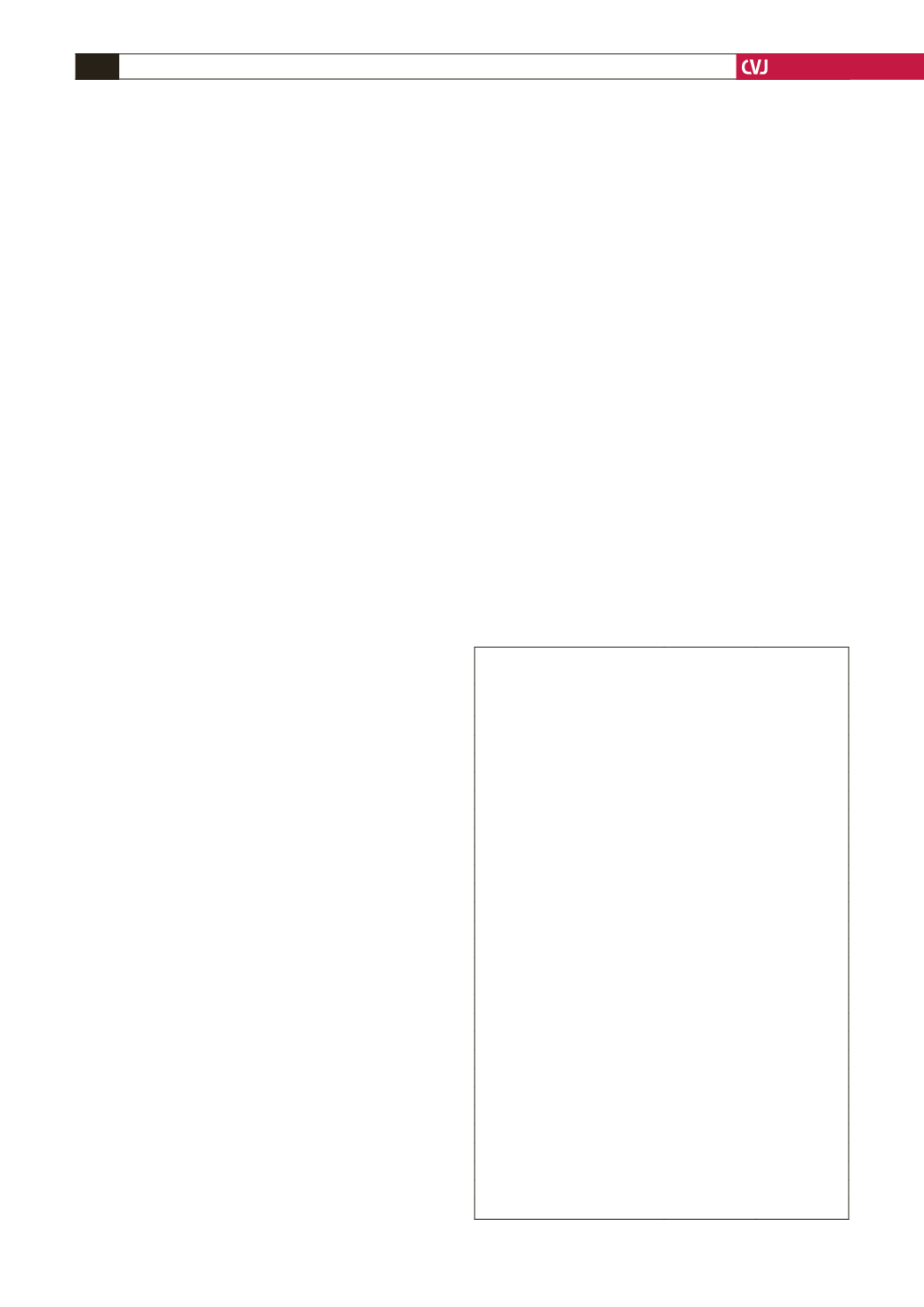

TABLE 1. DEMOGRAPHICAND INRVALUES FOR PATIENTS

FROMWESFLEURAND GUGULETHU HOSPITALS

Wesfleur

(

n

=

76)

Gugulethu

(

n

=

35)

Gender

Male

37.5

19.4

Female

62.5

80.6

Race

Black

5.3

100

White

5.3

0

Coloured

88.1

0

Unspecified race

1.3

0

Co-morbidities

Diabetes

13

23

Hypertension

61

58

Arthritis

16

14

Chronic obstructive airway disease

11

6

Peptic ulcers

8

3

INR values

INR

>

3.5

58.3

32.2

Gender vs INR

Male: INR

>

3.5

51.9 (

n

=

27)

50 (

n

=

6)

Female: INR

>

3.5

62.2 (

n

=

45)

28 (

n

=

25)

Age vs INR

Patients

>

40 years

86.1

58.1

Patients

>

40 years: INR

>

3.5

59.7 (

n

=

62)

33 (

n

=

18)

Patients

<

40 years: INR

>

3.5

40 (

n

=

10)

23 (

n

=

13)

Weight vs INR

Patients

>

70 kg

33.7

82.4

Patients

>

70 kg: INR

>

3.5

72 (

n

=

32)

35.7 (

n

=

14)

Patients

<

70 kg: INR

>

3.5

55 (

n

=

31)

33.3 (

n

=

3)