CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 1, January/February 2018

28

AFRICA

Descriptive statistics in the form of means and standard

deviations in the case of continuous data, and frequencies and

percentages in the case of categorical data were calculated. A

p

-value of

<

0.05 was considered significant. Ethical approval

for the study was obtained from the University of Pretoria Ethics

Committee (No. 125/2013).

Results

There were 6 536 deliveries at our hospital during the recruitment

phase of the study (1 April 2013 – 30 March 2015). Four

hundred and sixty-three (7.1%) women presented with severe

pre-eclampsia and 106 women were recruited to the study. Ten

women were lost to follow up. Data were therefore recorded for

96 women with severe pre-eclampsia and 45 controls.

Seventy-four (77.1%) women in the study group for whom

data were available fulfilled the World Health Organisation

(WHO) criteria for the classification of a maternal near miss. Of

the 96 women with severe pre-eclampsia, 14 were diagnosed with

chronic hypertension and four with diabetes prior to pregnancy.

At one year, the mean diastolic blood pressure and mean body

mass index was significantly higher among the women who had

pre-sclampsia during pregnancy compared to the normotensive

control group. Table 2 describes the demographic data of the

study population.

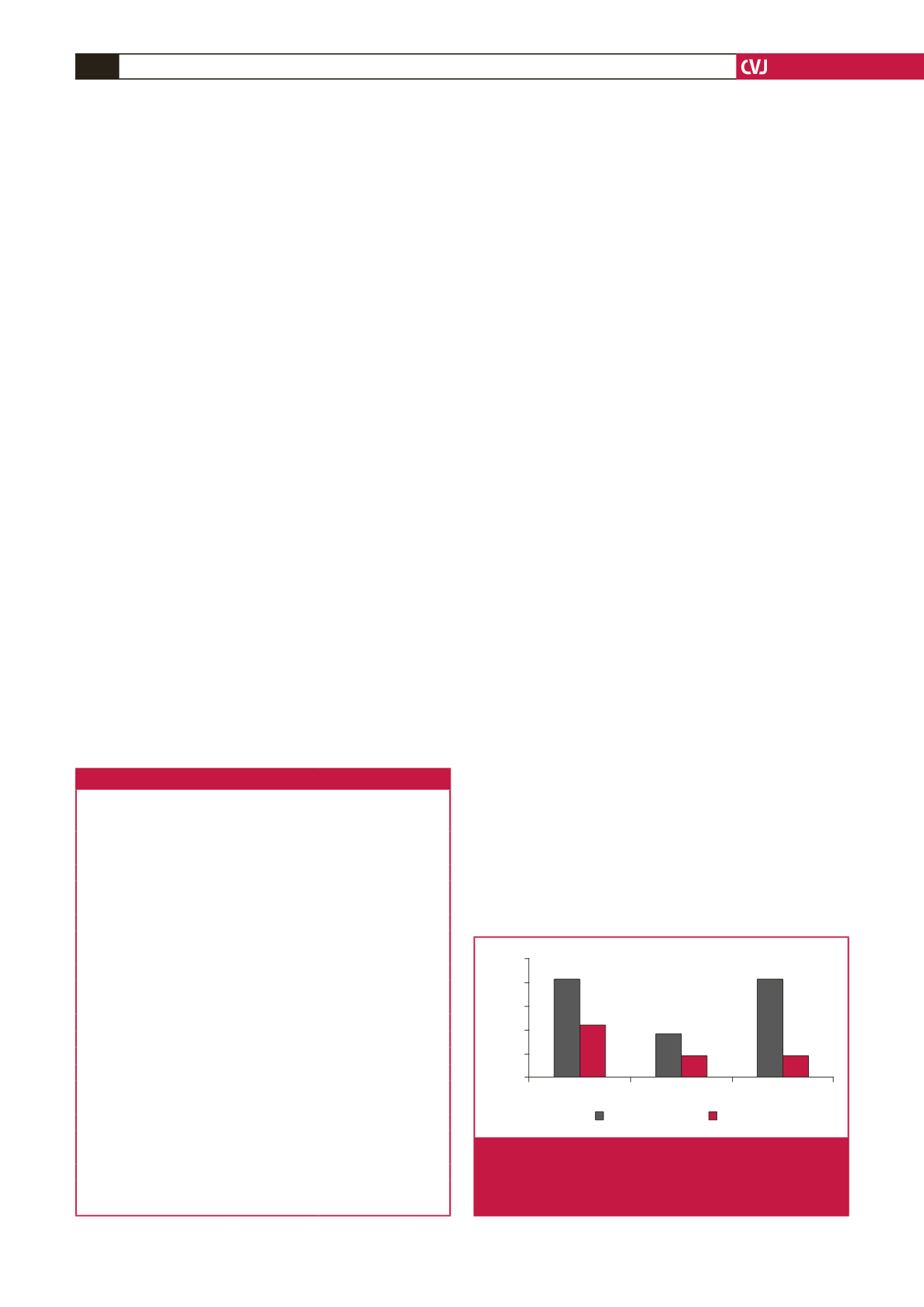

Twenty women (20.83%) with pre-eclampsia were diagnosed

with diastolic dysfunction at delivery compared with six (13.3%)

of the controls (

p

=

0.26). Of the 20 women who were diagnosed

with diastolic dysfunction at delivery, 13 (65%) had early-onset

pre-eclampsia, requiring delivery prior to 34 weeks. At one year,

11 (11.46%) women with pre-eclampsia were diagnosed with

diastolic dysfunction compared with three (6.67%) in the control

group (RR

=

1.67;

p

=

0.27).

Women with early-onset pre-eclampsia requiring delivery

prior to 34 weeks’ gestation had an increased risk of diastolic

dysfunction at one year post-partum (RR 3.41, 95% CI: 1.11–

10.5,

p

=

0.04) (Fig. 1). Delivery prior to 34 weeks was associated

with an increased risk of diastolic dysfunction even if patients

with chronic hypertension at one year were excluded from

the analysis (

p

=

0.02, 95% CI: 1.43–97.67) There was no

significant association between diastolic dysfunction and chronic

hypertension at one year (RR

=

2.02,

p

=

0.33, 95% CI: 0.57–

7.13). Echocardiographic measurements of diastolic function

after one year are shown in Table 3.

Left ventricular systolic function was normal and similar in

both groups, suggesting preservation of systolic function in both

pre-eclamptics and controls. There was a significant decrease

in lateral e

′

and a significant increase in A velocity between the

pre-eclamptic and control group at one year.

Discussion

Heart failure is a progressive condition, which begins with risk

factors for left ventricular dysfunction and progresses further to

asymptomatic changes in cardiac structure and function, finally

evolving into heart failure.

16

Myocardial remodelling starts

before the onset of symptoms. Diastolic dysfunction precedes

the onset of systolic dysfunction in 50% of cardiac diseases,

which further precedes the onset of heart failure.

5

The American College of Cardiology has highlighted the

importance of identifying asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction for

early intervention and improvement of outcome.

17

The risk for

left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is significantly associated

with higher age, body mass index (BMI), heart rate and systolic

blood pressure.

16

The prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in

a general population aged less than 49 years was found to be

6.8%, and 27.3% for the total population, which included study

subjects older than 70 years.

16

Zanstra

et al

. found that 24% of women with the metabolic

syndrome during pregnancy had diastolic dysfunction at six

months post-partum, compared to 6.3% of women with low-risk

pregnancies.

18

Obesity and diastolic hypertension were strong

correlates to diastolic dysfunction.

The rate of diastolic dysfunction at one year in the two

groups of women with early-onset pre-eclampsia (22.7%) and

low-risk pregnancies (6.7%) in our study were similar to rates

Delivery

1 year

Delivery <34 weeks

25

20

15

10

5

0

Control

Pre-eclamptic

p

=

0.04

p

=

0.27

p

=

0.26

Fig. 1.

Risk of diastolic dysfunction at delivery and at one

year, and at one year for sub-group of women with

early-onset pre-eclampsia requiring delivery prior to

34 weeks.

Table 2. Demographic data of the study population

Characteristics

Pre-eclamptic

group

(

n

=

96)

Control

group

(

n

=

45)

p

-value

Age, years

Mean (SD)

28.9 (6.83)

27.2 (7.14)

0.66

Range

18–46

20–42

Race

African,

n

(%)

86 (89.58)

38 (84.44)

Caucasian,

n

(%)

5 (5.20)

3 (6.67)

Coloured,

n

(%)

4 (4.17)

4 (8.89)

Indian,

n

(%)

1 (1.04)

0 (0)

Obstetric history

Parity mean (range)

1.3 (0–4)

1.6 (0–5)

Timing of delivery

<

34 weeks,

n

(%)

44 (45.83)

0 (0)

34–37 weeks,

n

(%)

25 (26.04)

5 (11.11)

>

37 weeks,

n

(%)

27 (28.13)

40 (88.89)

Medical conditions

Diabetic at 1 year,

n

(%)

6 (6.25)

0 (0)

Hypertensive at 1 year,

n

(%)

52 (54.17)

2 (4.44)

Haemoglobin at 1 year (g/dl)

Mean (SD)

12.02 (1.46)

12.42 (1.13)

0.15

Blood pressure at 1 year (mmHg)

Systolic, mean (SD)

128.01 (14.17)

115.08 (9.89)

0.08

Diastolic, mean (SD)

80.91 (14.47)

72.45 (9.16)

0.001

BMI at 1 year, mean (SD)

30.27 (7.55)

28.04 (3.64)

0.02