CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 6, November/December 2018

AFRICA

399

require laboratory evaluation and use of cardiovascular imaging

modalities that involve ionising radiation, which has been related

to teratogenesis, mutagenesis and childhood malignancy.

57

As

stated before, concerns related to safety of imaging tests must

always be balanced against the importance of accurate diagnosis

and thorough assessment of the pathological condition.

27

The indications for and limitations of the different diagnostic

procedures must be discussed, as well as their potentially harmful

effects during pregnancy, but if needed, chest radiography,

fluoroscopy, echocardiography and invasive angiography may

all be used. Echocardiography appears to be completely safe for

both the mother and foetus.

58

Counselling for pregnant women should be given according

to the CARPREG (CARdiac disease in PREGnancy) risk

score

47

or the modified World Health Organisation (WHO)

classification.

59

The fact that most women present to antenatal

clinics after 20 weeks of gestation has implications for their

functional assessment, and limits the option for termination

of pregnancy. In any case, care should be given to discussing

maternal and offspring risks, namely choices of anticoagulant

therapy, as well as risks of miscarriage, early delivery and small-

for-gestational-age babies. Complications such as heart failure

and valve thrombosis must also be discussed as they may occur

beyond the immediate delivery period. Finally, side effects of

common drugs need to be openly discussed.

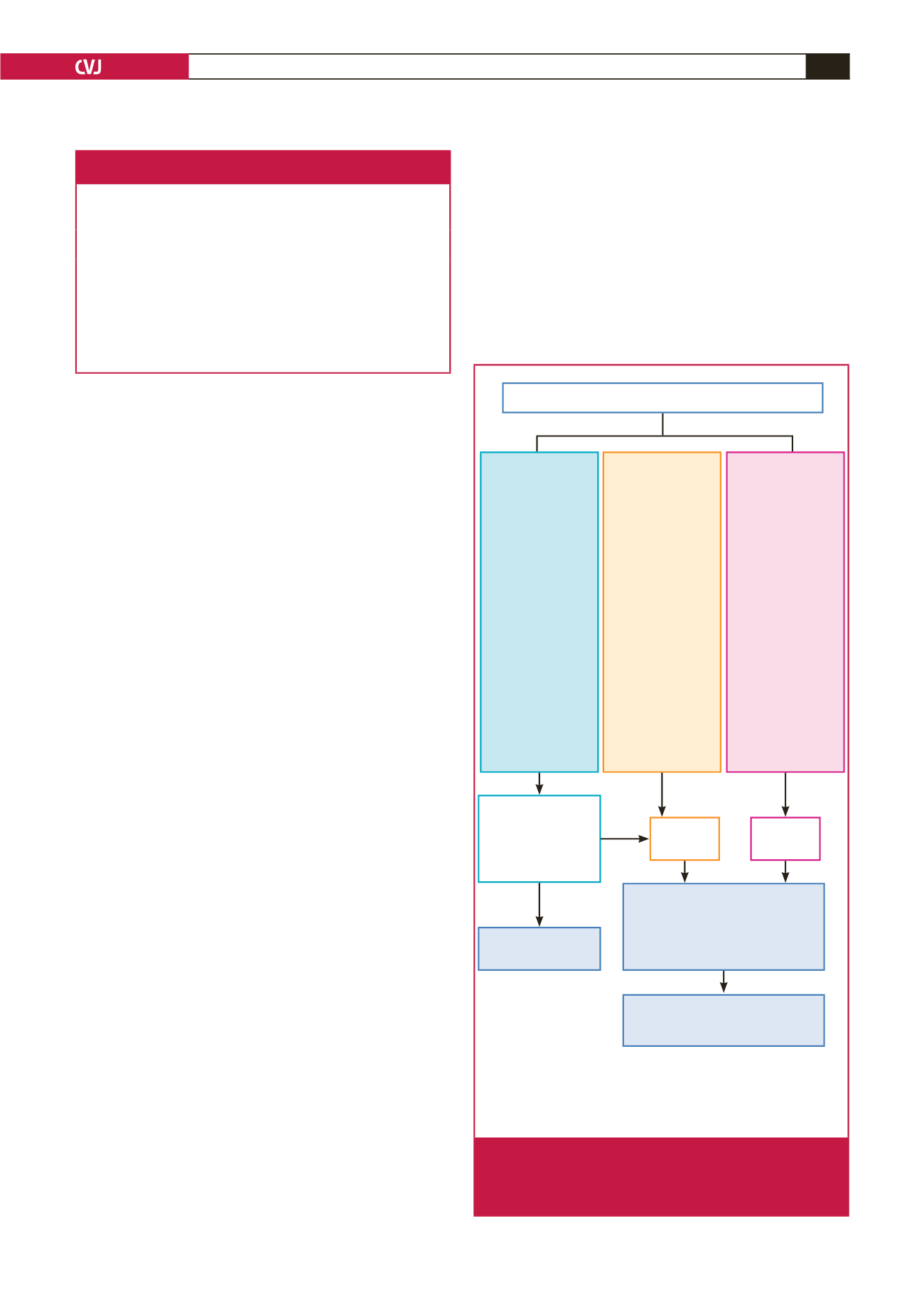

Algorithms for the identification and management of

pregnant patients with cardiovascular disease can help by

improving care, guiding screening of heart disease in all pregnant

women, and detecting those with RHD (Fig. 3). They should

distinguish between women with known or recently detected

cardiovascular disease who are controlled and should undergo

risk assessment, from those in heart failure needing immediate

ambulance transfer to a tertiary centre.

25

More importantly,

the algorithms must identify women at high risk who may need

careful monitoring beyond the usual peripartum period.

Labour and postpartum care

Induction, management of labour, delivery and postpartum

care require specific expertise and joint management by the

obstetrician, cardiologist and anesthaesiologist, preferably in

an experienced tertiary care centre. This is true for women with

native valve pathology but is more important in those with

prosthetic valves.

The treating specialist should prepare a detailed management

plan, considering access to care outside of normal working

hours. Management needs to be individualised due to the

complexity of cases but also due to lack of prospective data.

25

Based on consensus, the preferred mode of delivery is vaginal.

A delivery plan should be prepared until week 34, including

information on the timing of delivery (spontaneous/induced),

method of induction, use of general or regional anaesthesia, level

of monitoring, needs and details for post-partum monitoring,

and sub-acute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis. In addition,

specific instructions for anticoagulation should be documented.

As recently summarised by Sliwa

et al

.,

25

delivery in

anticoagulated women with prosthetic valves needs to follow

a certain algorithm of care. At 36 weeks, most patients are

Table 1. Pre-conception evaluation in women with rheumatic heart

valve disease planning a pregnancy or assessment in early pregnancy

• Careful history, family history, and physical examination (if feasible, include

screening for connective tissue disorders)

• 12-lead electrocardiogram

• Echocardiogram including assessment of left- and right-ventricular and valve

function

• Laboratory assessment for risk factors: antistreptolysin O, erythosedimenta-

tion rate, haemoglobin, human immunodeficinecy virus test

• Exercise test to be considered for objective assessment of functional clas-

sification

• Careful counselling: maternal risks for complications and mortality, risk

of miscarriage, early delivery and small-for-gestational-age information on

choices of therapy (heparin vs vitamin K), when applicable, risk of foetal

congenital defect – inheritance risk

Primary and secondary care maternal facility

Modified WHO

classification I

• Previously diag-

nosed hyperten-

sion, diabetes,

morbid obesity

(BMI > 35 kg/m

2

)

• Successfully

repaired simple

lesions

• Uncomplicated,

small or mild mitral

valve prolapse,

pulmonary stenosis

• Palpitations – no

dizziness

Modified WHO

classification

III–IV

• Mechanical valve

and symptoms

• Complex congenital

or cyanotic heart

disease

• Pulmonary hyper-

tension any cause

• Previously diag-

nosed peripartum

cardiomyopathy

• Severe ventricular

impairment (EF <

45%, NYHA FC > II)

• Severe mitral

stenosis and aortic

stenosis

• Aortic dilataion

> 45 mm (bicuspid

AV, Marfan)

Modified WHO

classification II

• Unoperated ASD

and VSD

• Repaired tetralogy

of Fallot and coarc-

tation

• Arrythmias and

dizziness

• Mild left ventricular

impairment (EF >

45%, NYHA FC II)

due to newly diag-

nosed PPCM or HT

heart failure

• Previously diag-

nosed RHD with

murmurs and/or

recently assessed

asymptomatic

mechanical valve

Tertiary care

maternal facility

Tests: BP, ECG,

echocardiogram and

assess for murmurs

Non-urgent

referral

Urgent

referral

Joint cardiac–obstetric–

anaesthetic CDM team

Consulting with paediatric cardiologist,

endocrinologist, radiologist, HIV

specialist and others

Follow up with

maternity service

Postpartum referral to main cardiac

clinic, if indicated, for management

and possible cardiothoracic surgery

Abnormal

Normal

BMI: body mass index; ECG: electrocardiogram; ASD: atrial septal defect;

VSD: ventricular septal defect; EF: ejection fraction; NYHA FC: New York

Heart Association functional class; PPCM: peripartum cardiomyopathy;

HT: hypertension; AV: aortic valve

Fig. 3.

Referral algorithm recommended for screening and

management of women with suspected or known

cardiovascular disease at primary and secondary

level of care.