CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 23, No 7, August 2012

AFRICA

e3

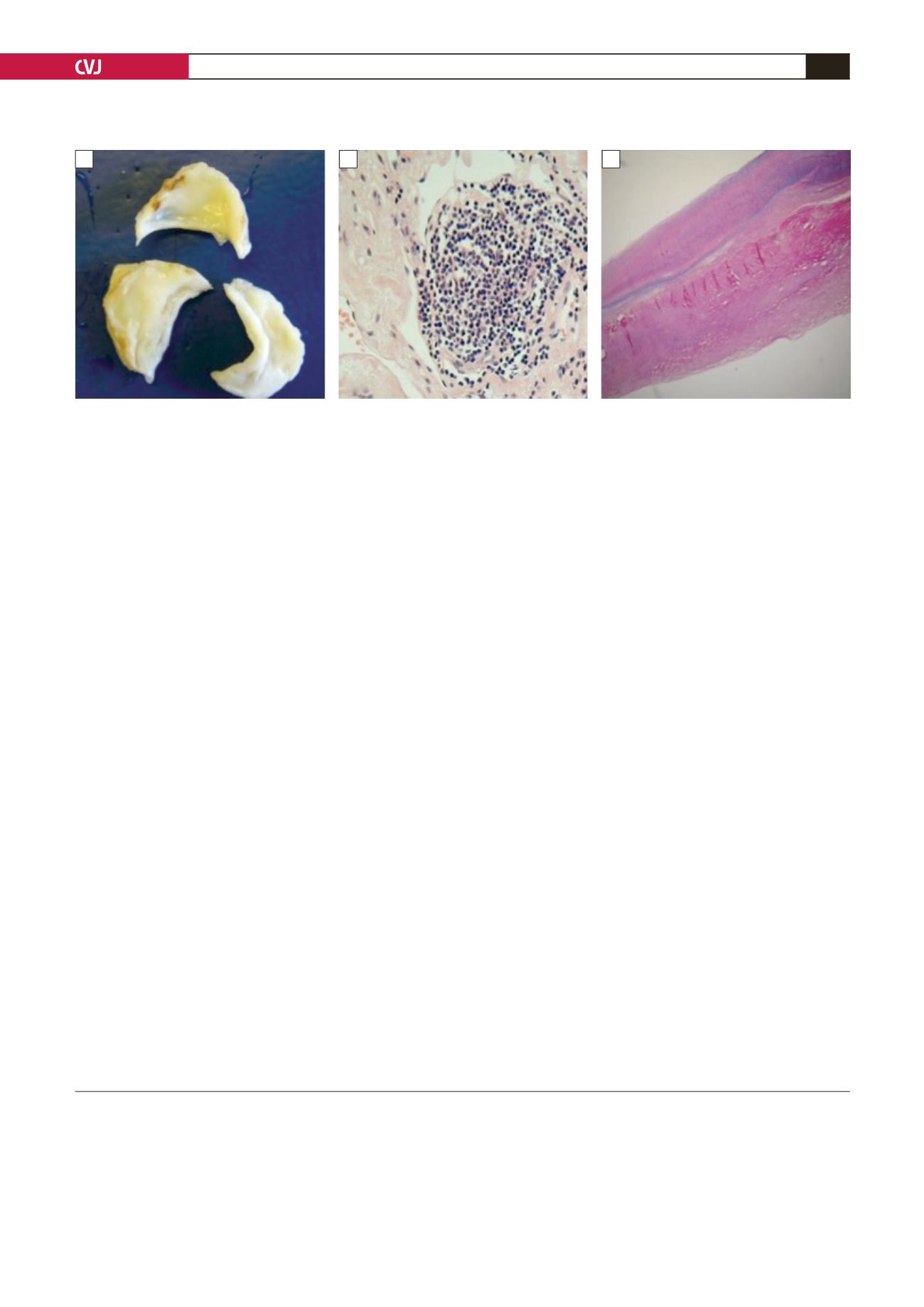

neovascularisation and focal lymphocyte infiltration (Fig. 3B,

C). There was no evidence of sarcoidosis in the valve or

surrounding lymph node. No rheumatoid nodules, granuloma or

calcification were seen. These findings supported the diagnosis

of valvular heart disease secondary to RA.

Post-operative echocardiography showed a well-seated

prosthetic aortic valve with no AR, mild MR, no TR, and no

pericardial collection. At one month, the LVEDD was improved

to 6.0 cm. Echocardiography 10 months post surgery showed

a well functioning aortic prosthetic valve with a significant

reduction in LVEDD from 6.5 cm to 4.6 cm. Mitral and tricuspid

valve function was improved, with no regurgitation seen 10

months post repair.

Discussion

Pre-operative non-invasive cardiac imaging supported a diagnosis

of severe valvular heart disease due to RA, and aggressive steps

were taken to treat his heart failure. Valve thickening was

seen on echocardiography, which is a distinctive feature that

provides evidence of valve involvement in RA.

5

Myocardial

fibrosis demonstrated on cardiac MRI gave further support to

this diagnosis. The pattern of delayed enhancement helped to

distinguish from other causes of myocardial fibrosis, including

sarcoidosis and ischaemic cardiomyopathy.

Most patients with RA-associated valvular heart disease

have mild valvular insufficiency due to a slowly progressive

granulomatous valvulitis.

2

Rapidly progressive, severe

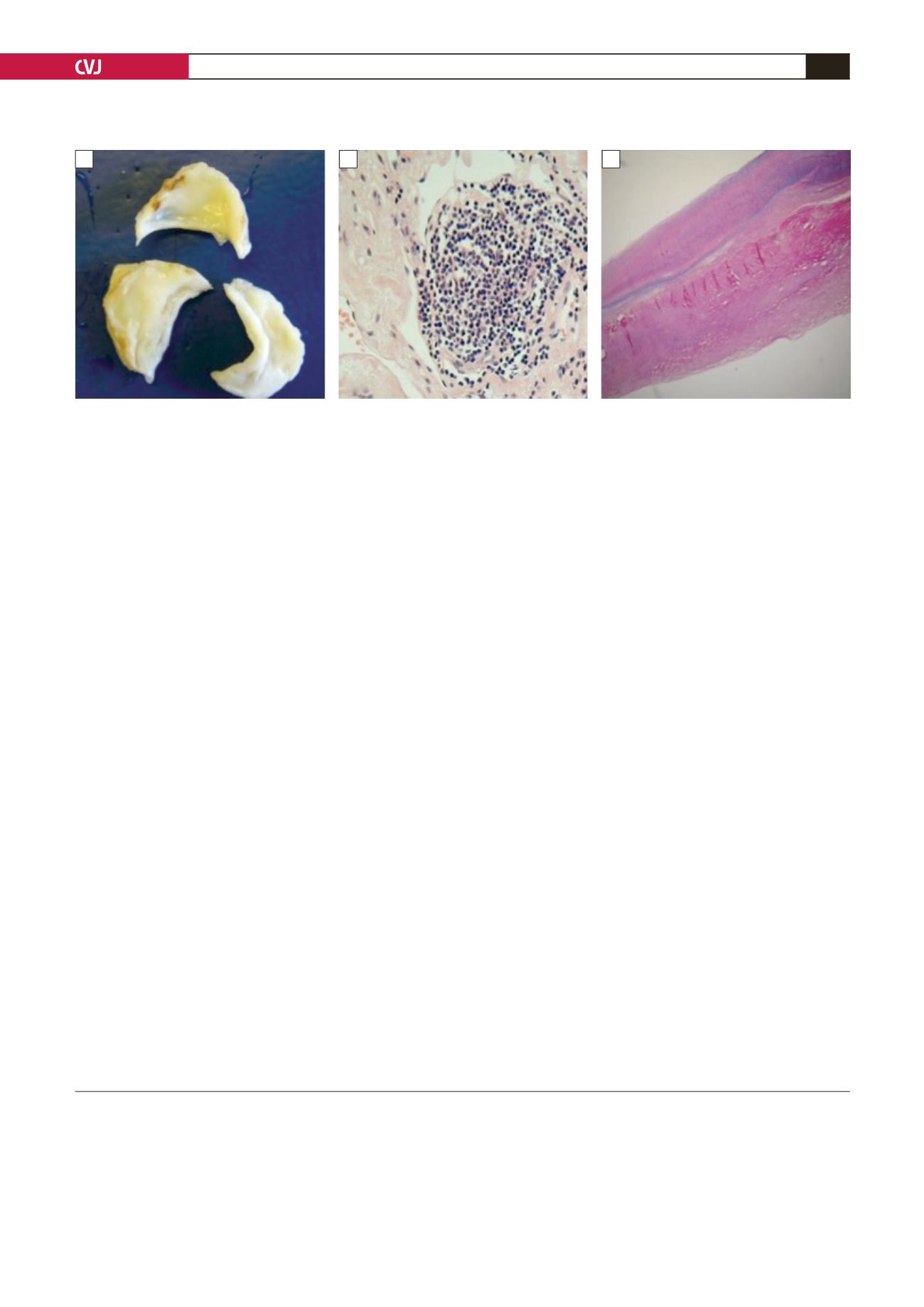

Fig. 3. Macroscopic view of the aortic valve showing thickened and retracted valve cusps (A). Histology slides showing

lymphocyte infiltration and new vessel formation (B), and fibroelastic tissue (C).

non-granulomatous valve disease has also been described in

RA.

2

This was the diagnosis in our patient.

Conclusion

This case report highlights potential difficulties in the

management of patients with severe heart failure due to

rheumatoid arthritis. Early surgical intervention is often the best

treatment option in this setting, as severe left ventricular failure

is unlikely to respond to medical treatment alone and valve

replacement surgery can improve left ventricular function and

prolong survival.

6

References

1.

Lebowitz W. The heart in rheumatoid arthritis.

Ann Intern Med

1063;

58

: 102–123.

2.

Libby P, Bonow RO, Zipes DP, Mann DL. Rheumatic diseases and

the cardiovascular system. In:

Braunwald’s Heart Disease

. 8th edn.

Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier 2007; 2094–2096.

3.

Voskuyl AE. The heart and cardiovascular manifestations in rheumatoid

arthritis.

Rheumatology

2006;

45

: iv4–iv7.

4.

Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular complications of rheumatoid arthritis –

assessment, prevention and treatment.

Rheum Dis Clin North Am

2010;

36

(2): 405–426.

5.

Roldan CA, DeLong C, Qualls CR, Crawford MH. Characterization of

valvular heart disease in rheumatoid arthritis by transoesophageal echo-

cardiography and clinical correlates.

Am J Cardiol

2007;

100

: 496–502.

6.

Levine AJ, Dimitri WR, Bonser RS. Aortic regurgitation in rheumatoid

arthritis necessitating aortic valve replacement.

Eur J Cardiothorac

Surg

1999; 213–214.

A

B

C