CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 2, March 2013

18

AFRICA

Discussion

The prevalence of AAA in the general population aged 50 to

64 years seemed lower in Seychelles than in North America

or Europe. In North America, in participants aged 50–54/55–

59/60–64 years, the prevalence of AAA was 0.9/2.5/4.2% in

smokers and 0.2/0.5/0.9% in non-smokers, respectively.

4,7

In

Norway, the prevalence of AAA in men/women was 1.9/0% and

6.0/1.1% at ages 45–54 and 55–64 years, respectively.

13

In the

Netherlands the prevalence of AAA in men/women was 0.9/0.2%

and 3.1/0.4% at ages 55–59 and 60–64 years, respectively.

16

In contrast to what was recently described in a population of

mainly symptomatic aortic aneurysm patients in Kenya, we did

not find a female predominance for the diagnosis of AAA in

Seychelles. This was despite the predominant African descent of

the population and the prevalence of high blood pressure in the

50- to 64-year age category, which was the leading risk factor

associated with aortic aneurysms in this study.

17

This apparent

inconsistency might be due to methodological factors, such as

gender differences in health-related habits, since the Kenyan study

was based on hospital records and not on population-based data.

A low prevalence of AAA in Seychelles might be consistent

with a high prevalence of diabetes and the predominantly African

descent of the population, which are two factors reported to be

inversely associated with AAA.

6,7

It is however at odds with a

high prevalence of smoking (in men), high blood pressure and

hypercholesterolaemia in the Seychelles population.

Alternatively, we cannot exclude some imprecision in our

estimates in view of the relatively small size of our sample and

broad confidence intervals, although the population-based design

of the study as well as the high participation rate strengthens the

reliability of our epidemiological data. On the other hand, the

seemingly higher prevalence of aortic ectatic dilatation could

announce increasing rates of AAA in the next decades as the

population becomes exposed to high risk-factor levels over long

periods of time.

Furthermore, because of a high prevalence of AAA risk

factors, such as current smoking (28% in men and 4% in women

aged 40–49 years) or high blood pressure (35% in the 40–49-

year population) in younger age groups with a lower prevalence

of ‘protective factors’ such as diabetes mellitus (11.7% in

the 40–49-year population), ectatic lesions might appear at a

younger age in Seychelles than in North America or Europe.

However, given the small rate of expansion of small lesions over

time, the finding of true AAA in subjects aged less than 50 years

is unlikely.

18

Conclusion

Pending further data on the prevalence of AAA in older age

categories, our results do not support routine screening ofAAA in

the selected population. This is consistent with recommendations

for populations in Western countries.

5

References

1.

Ashton HA, Buxton MJ, Day NE, Kim LG, Marteau TM, Scott RA,

et al

. Multicenter Aneurysm Screening Study Group. The Multicenter

Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic

aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomized controlled trial.

Lancet

2002;

360

: 1531–1539.

2.

Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Lawrence-Brown MM, Le MTQ, Spencer

CA, Tuohy RJ,

et al

. Population based randomised controlled trial on

impact of screening on mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Br

Med J

2004;

329

: 1259–1264.

3.

Lindholt JS, Juul S, Fasting H, Henneberg EW. Screening for abdomi-

nal aortic aneurysms: single center randomised controlled trial.

Br Med

J

2005;

330

: 750–754.

4.

Fleming C, Witlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdomi-

nal aortic aneurysm: a best evidence systematic review for the U.S

Preventive services Task Force.

Ann Intern Med

2005;

142

: 203–211.

5.

Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Litooy FN, Bandyk

D,

et al

. Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm

detected through screening.

Ann Intern Med

1997;

126

(6): 441–449.

6.

Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Chute EP, Hye RJ, Makaroun MS,

et al.

and the Aneurysm Detection and Management Veterans Affairs

Cooperative Study Investigators. The aneurysm detection and manage-

ment study screening program. Validation cohort and final results.

Arch

Intern Med

2000;

160

: 1425–1430.

7.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic

aneurysm: recommendation statement.

Ann Intern Med

2005;

142

:

198–202.

8.

Puech-Leao P, Molnar LJ, de Oliveira IR, Cerri GG. Prevalence of

abdominal aortic aneurysms – a screening program in Sao Paulo,

Brazil.

Sao Paulo Med J

2004;

122

(4): 158–160.

9.

Yii MK. Epidemiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm in anAsian popu-

lation.

ANZ J Surg

2003;

73

(6): 393–395.

10. Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Kitua A, Riesen WF, Paccaud F, Darioli R. High

prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the Seychelles (Indian

Ocean).

Arterioscler Thromb

1991;

11

(6): 1730–1736.

11. Bovet P, Romain S, Shamlaye C, Mendis S, Darioli R, Riesen W,

et al

.

Divergent 15-year trends in traditional and metabolic risk factors of

cardiovascular diseases in the Seychelles.

Cardiovasc Diabetol

2009;

8

: 34.

12. Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Gabriel A, Riesen W, Paccaud F. Prevalence of

cardiovascular risk factors in a middle-income country and estimated

cost of a treatment strategy.

BMC Publ Hlth

2006;

6

(1): 9.

13. Singh K, Bonaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjork L, Solberg S. Prevalence of

and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based

study. The Tromso Study.

Am J Epidemiol

2001;

154

: 236–244.

14. Hirsch A, Haskal Z, Hertzer N, Bakal C, Creager M, Halperin J,

et al

.

ACC/AHA 2005 Practice guidelines for the management of patients

with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and

abdominal aortic).

Circulation

2006;

113

: e463–e654.

15. Basnyat PS, Aiono S, Warsi AA, Magee TR, Galland RB, Lewis MH.

Natural history of the ectatic aorta.

Cardiovasc Surg

2003;

11

(4):

273–276.

16. Pleumeekers HJCM, Hoes AW, van der Does E, van Urk H, Holman

H, de Jong PTVM, Grobbee DE. Aneurysm of the abdominal aorta

in older adults. The Rotterdam Study.

Am J Epidemiol

1995;

142

:

1291–1299.

17. Ogeng’o JA, Olabu BO, Kilonzi JP. Pattern of aortic aneurysms in an

african country.

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg

2010;

140

: 797–780.

18. Brady A, Thompson SG, Fowkes FG, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT for

the UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Abdominal aortic aneurysm

expansion: risk factors and time intervals for surveillance.

Circulation

2004;

110

: 16–21.

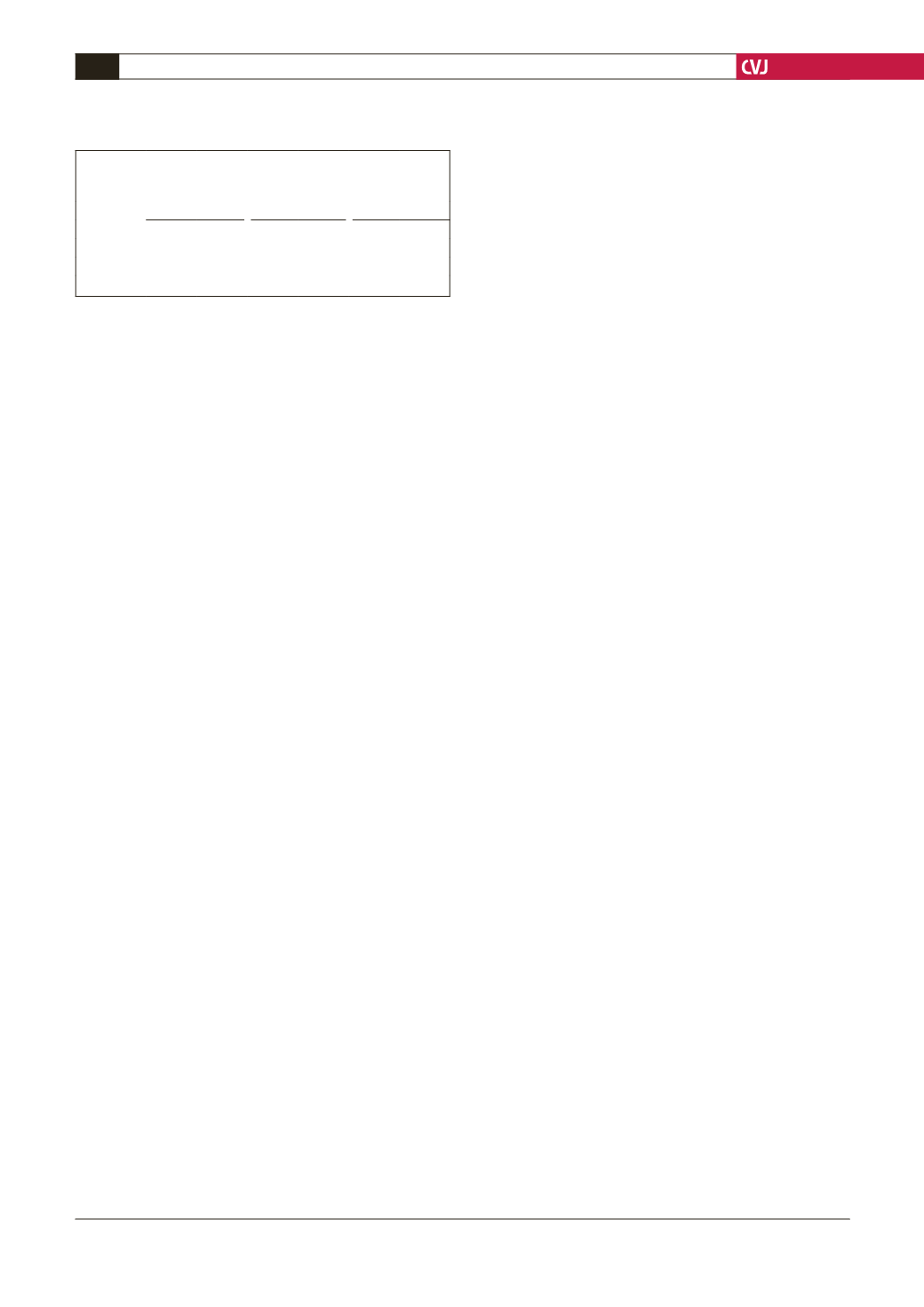

TABLE 1. PREVALENCE OFANEURYSM OR ECTASY

OF THEABDOMINALAORTA IN THE GENERAL

POPULATION OF SEYCHELLESAGED 50–64YEARS

Men (

n

= 151)

Women (

n

= 178)

Total (

n

= 329)

% 95% CI

% 95% CI

% 95% CI

Aneurysm 0.7 0–2.0 0

0.3 0–0.9

Ectasy

2.0 0–4.2 0.6 0–1.7 1.2 0–2.4

Either

2.7 0.1–5.2 0.6 0–1.7 1.5 0.2–2.8