CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 1, January/February 2017

AFRICA

33

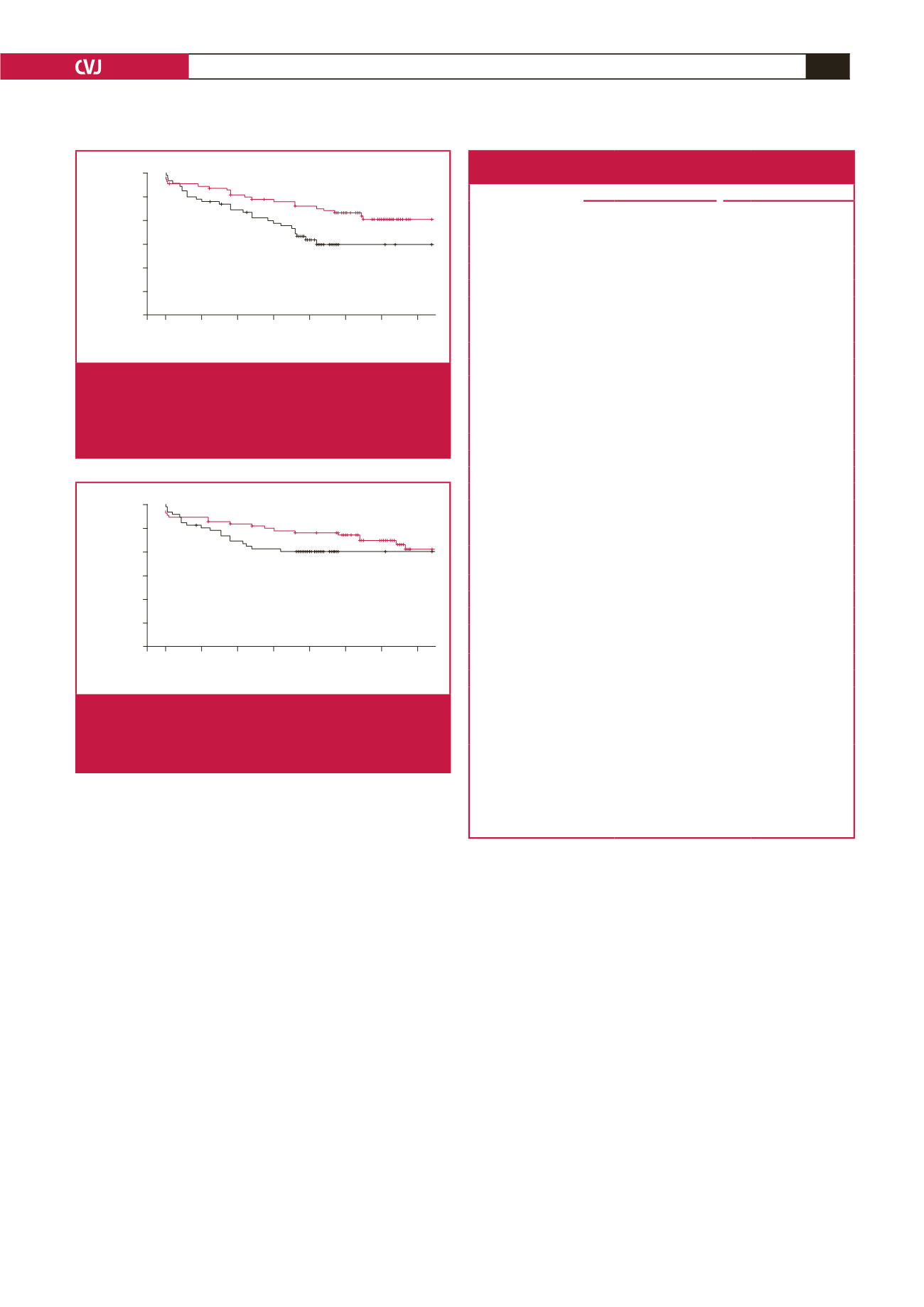

Kaplan–Meier analysis of freedom from MACE revealed

significantly lower event-free survival rates in the OPCAB group

(ONBHCAB, 84.9%; OPCAB, 90.3%;

p

=

0.029 by the log-rank

test) (Fig. 1). Kaplan–Meier analysis of freedom from mortality

revealed no significant difference between the two groups

(ONBHCAB, 90%; OPCAB, 90.5%;

p

=

0.16 by the log-rank

test) (Fig. 2). In the multivariable Cox proportional hazard

model, the mean number of transfused RBC units was the only

independent significant predictor of MACE (Table 3).

Discussion

OPCAB has the potential to reduce several of the adverse effects

of CCAB because of elimination of CPB, the harmful

effects of

cardioplegia, the cessation of coronary blood flow, and excessive

aortic manipulation. Its superiority compared with CCAB in

early or mid-term outcomes has therefore been reported by many

authors.

9-12

However, the risk of haemodynamic instability during

surgery, causing incomplete revascularisation, especially in the

hands of an inexperienced surgeon, remains the major limitation

of this method.

A third method, ONBHCAB, reduces myocardial ischaemia,

maintaining coronary blood flow, preserves haemodynamic

stability with the use of CPB, and permits cardiac manipulation.

Moreover, it also limits aortic manipulation and protects the

heart from post-cardioplegic intimal damage, as well as OPCAB

surgery. A recent meta-analysis showed that ONBHCAB was

associated with significantly fewer peri-operative MIs and less

IABP use, shorter CPB time, and lower total blood loss compared

with CCAB. However, it was similar in terms of cerebrovascular

events, renal dysfunction, pulmonary complications, re-operation

due to bleeding, inotropic agent use, intensive care unit stay,

hospital stay, ventilation time, number of anastomoses, early

mortality and mid-term survival rates after CABG.

7

Another recent meta-analysis revealed that OPCAB was

associated with significantly fewer incidents of peri-operative

low cardiac output (LCO) and renal dysfunction, less total

blood loss, fewer RBC transfusions, shorter ventilation times and

lengths of ICU or hospital stay, but similar rates of in-hospital

or long-term mortality, peri-operative MIs and cerebrovascular

accidents within the first 30 days compared with CCAB.

Moreover, OPCAB was also associated with an increased risk of

repeat revascularisation within the first month and significantly

lower numbers of performed grafts.

Follow up (months)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Freedom from MACE

1.00

0.95

0.90

0.85

0.80

0.75

0.70

ONBHCAB

OPCAB

p

=

0.029

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates in the propensity-matched

populations. Freedom from major adverse cardio-

vascular events (MACE). Red lines indicate OPCAB

group, black lines indicate ONBHCAB group (

p

=

0.029

by the log-rank test).

Table 3. Cox proportional hazard model for MACE at the long-term follow

up of propensity-matched patients

Univariate analysis

Multivariate analysis

Characteristics

HR

95% CI

p

-value HR 95% CI

p

-value

Pre-operative

characteristics

Age

1.026 0.992–1.061 0.14

Males

1.519 0.77–2.998 0.22

EuroSCORE

1.299 1.140–1.479

<

0.001* 1.051 0.873–1.265 0.59

Obesity

(BMI

≥

30 kg/m

2

)

1.891 1.006–3.557 0.048* 1.681 0.812–3.481 0.16

CrCl

0.999 0.991–1.007 0.75

COPD

2.534 0.999–6.425 0.05 1.102 0.317–3.826 0.87

Diabetes mellitus

1.297 0.705–2.389 0.4

Cerebrovascular

disease

1.439 0.446–4.641 0.54

Peripheral vascular

disease

2.335 1.183–4.609 0.01* 0.982 0.366–2.634 0.98

Previous MI

2.619 1.454–4.716 0.001* 1.764 0.808–3.851 0.15

Impaired LV function 1.951 1.074–3.542 0.02* 1.186 0.529–2.659 0.68

USAP

1.446 0.796–2.625 0.22

Previous PCI

0.727 0.176–3.000 0.65

Number of diseased

vessels

1.806 0.923–3.534 0.08 1.435 0.664–3.099 0.35

Operative factors

Number of distal

anastomoses

0.921 0.658–1.288 0.63

CPB time

1.005 0.991–1.019 0.51

Total blood loss (ml) 1.001 1.000–1.002 0.18

RBC (units)

1.328 1.141–1.545

<

0.001* 1.218 1.089–1.361 0.001*

Postoperative

inotropic support

1.847 0.913–3.733 0.08 1.047 0.584–7.825 0.25

Peri-operative MI

2.764 1.170–6.530 0.02* 1.642 0.474–5.695 0.43

Renal complications 2.131 0.951–4.778 0.06 0.836 0.269–2.597 0.75

Neurological

complications

2.554 0.914–7.135 0.07 2.137 0.584–7.825 0.25

Early rehospitalisa-

tion (

<

30 days)

2.852 1.273–6.387 0.011* 1.256 0.410–3.851 0.69

*Statistically significant difference.

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graftıng; CI, confidence

interval; CrCl, creatinine clearance; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease

;

DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; LV, left ventricle; MI, myocardi-

al infarction; ONBHCAB, on-pump beating heart coronary artery bypass surgery;

OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery; PCI, percutaneous coronary

intervention; RBC, red blood cell, USAP, unstable angina pectoris.

Follow up (months)

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Freedom from mortality

1.00

0.95

0.90

0.85

0.80

0.75

0.70

ONBHCAB

OPCAB

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates in the propensity-matched

populations. Freedom from mortality. Red lines indi-

cate OPCAB group, black lines indicate ONBHCAB

group (

p

=

0.16 by the log-rank test).