CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

AFRICA

219

predictor of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients

with diabetes.

22

Hypertension is also a major risk factor for

myocardial infarction and stroke,

12,23,24

and indeed hypertension is

the leading risk factor for mortality worldwide.

5,25-28

Additionally,

hypertension is a major causal factor of end-stage kidney failure,

blindness and non-traumatic amputation in people with diabetes,

where attributable risks are 50, 35 and 35%, respectively.

16

Unfortunately the majority of people with hypertension in

sub-Saharan Africa do not know they have it, and most are not

on treatment. This reflects the low level of knowledge of the

dangers of untreated hypertension in this population.

10

In sub-Saharan Africa there is still a lack of awareness

about the growing problem of NCDs, which, unfortunately, is

often coupled with the absence of a clear policy framework for

prevention and management.

7

Given the long-term decreased

productivity associated with hypertension among diabetics,

identifying and treating a large proportion of patients has the

potential to generate tremendous social and economic benefits

in this region.

5,29-31

In this study we sought to determine the prevalence and

factors associated with hypertension among newly diagnosed

adult diabetic patients in a national referral hospital in Uganda.

These findings are not only necessary, but also contribute to

the diagnosis and management of DM and hypertension in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

This study was carried out in the diabetes out-patient clinic,

the medical endocrine ward and the medical emergency ward

of Mulago National Referral Hospital. It is the only national

referral hospital for Uganda and is the teaching hospital for

Makerere University, with a bed capacity of 1 500. Mulago

Hospital receives referrals from all parts of the country including

from neighbouring countries such as Southern Sudan, the

Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. The study

population is representative of the Ugandan diabetic population.

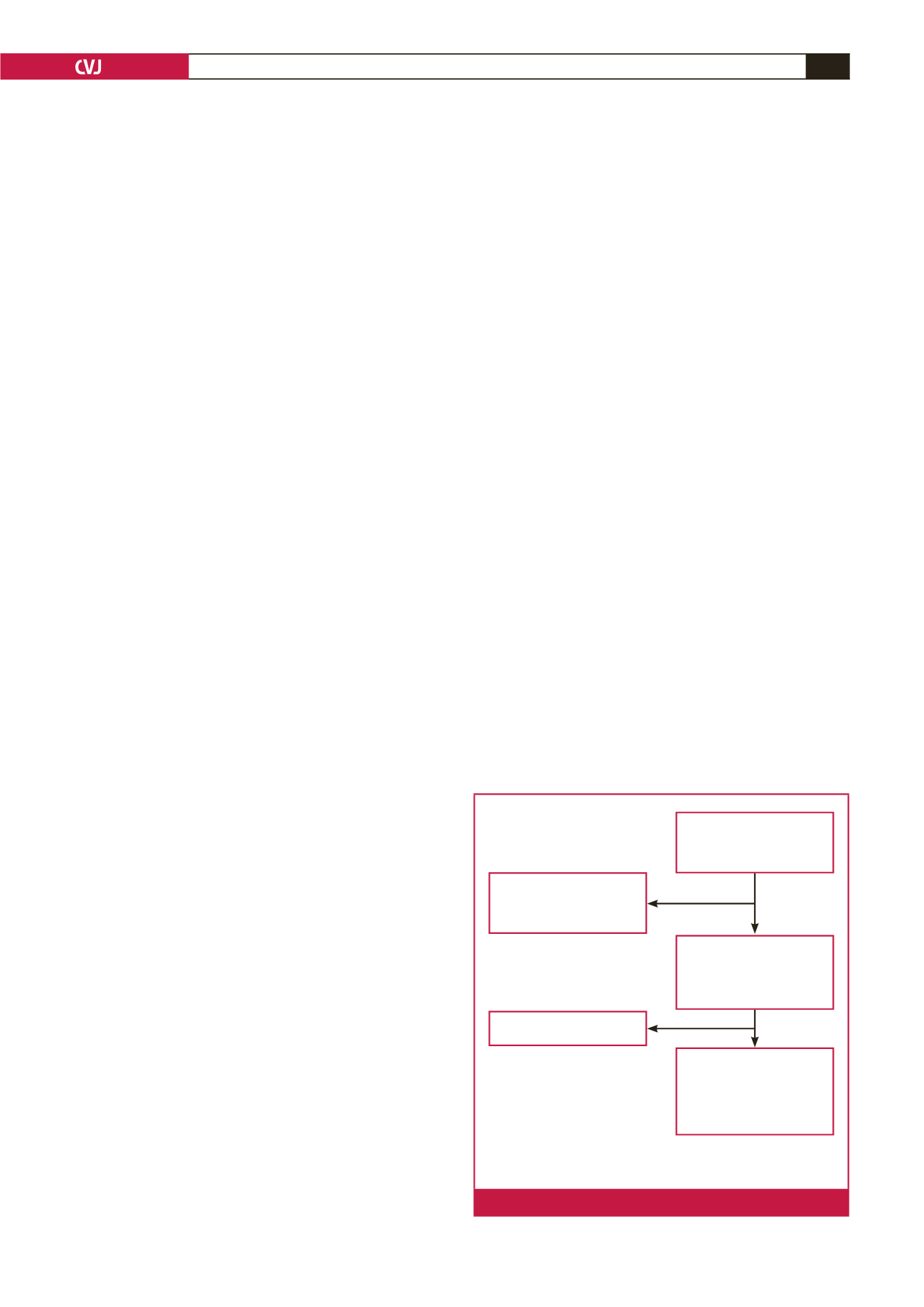

This was a cross-sectional study among 201 newly diagnosed

diabetic patients at Mulago Hospital in Uganda, conducted

between June 2014 and January 2015. All newly diagnosed

diabetic patients aged 18 years and above attending the diabetes

clinic or admitted to the medical wards of Mulago Hospital

during the study period, who met the inclusion criteria and

provided informed consent, were recruited consecutively. We

excluded patients with urinary tract infection in order to avoid

confounding in microalbuminuria, and those who were unable to

provide the necessary information. Fig. 1 illustrates the patient

recruitment flow.

Institutional consent was sought from the Department of

Medicine, Makerere University, Mulago National Referral

Hospital and the School of Medicine research and ethics

committee of Makerere University College of Health Sciences.

All study participants provided written informed consent for

involvement in the study. Enrolment was totally free and

voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw at any time

without any consequences. The patients’ records/information

was anonymised and de-identified prior to analysis.

We took a focused history and performed a specific physical

examination todeterminebiophysicalmeasurements. Information

gathered was entered into a pre-tested questionnaire. We assessed

the following factors: patients’ demographic data, history of

hypertension, age, physical exercise at work and leisure, marital

status, date of diagnosis of DM, drug history, occupation,

education level and last normal menstrual period.

Body mass was measured to the nearest kilogram using a

Secco weighing scale, height was measured in metres using a

non-stretchable tape, and these were used to compute body mass

index (BMI). Waist and hip circumferences were measured and

waist-to-hip ratios were determined for all patients.

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA

1c

) was measured by automated

high-performance liquid chromatography. Other investigations

included urinalysis and microalbuminuria using albumin-to-

creatinine ratio.

Echocardiography parameters were acquired using a

commercially available machine, Phillips HD11XE (Eindhoven,

the Netherlands), with two-dimensional, M-mode and Doppler

capabilities. It was used according to the American Society of

Echocardiography guidelines.

32

Blood pressure was measured using a mercury

sphygmomanometer, according to the American Heart

Association guidelines for the auscultatory method of blood

pressure assessment.

33

The degree of precision of blood pressure

measurement in this study was

±

2 mmHg.

33

Hypertension

was defined as present if subjects were on anti-hypertensive

medication, had a history of hypertension and/or evidence of

hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg).

Statistical analysis

Data were double entered in a database developed with Epidata

version 3.1, validated, and inconsistences were cleared. The

data were then exported to Stata 13 for analysis. Continuous

data were summarised using measures of central tendency while

categorical data were summarised as frequencies and percentages

and presented in tables. Prevalence was presented as percentages

Screened 263 newly

diagnosed diabetic patients in

MOPD, Ward 3B Emergency

and Ward 4B Endocrine

Excluded 46:

20: age below 18 years

5: declined to participate

21: too sick to give information

Completed history,

examination and questionnaire

for 218 patients. Performed

urinalysis for microscopy and

ACR. HbA

1c

was determined.

Excluded 16 with

urinary tract infection

Enrolled 201 patients. Cardiac

echo was done for LVH, wall

motion, diastolic and systolic

function by the principle inves-

tigator first and then reviewed

by a cardiologist

MOPD: Mulago out-patient department, ACR: albumin-to-creatinine

ratio, HbA

1c

: glycated haemoglobin, LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow chart.