CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 25, No 5, September/October 2014

AFRICA

247

rate to be 13%, which was increased to 24% with combined

surgery.

13

In our study, in-hospital mortality was 8.7% in patients

with isolated AVR and 16.7% in patients with combined surgery.

In addition, early reports in the elderly have shown mortality

rates of 2–10% for isolated AVR.

14,15

Concomitant CABG was also identified as an independent

predictor in a clinical series.

16

However, in a study including 450

patients aged

≥

80 years, Unic

et al

.

17

showed that concomitant

CABG did not affect the late survival rate.

In our study, we did not find any correlation between

combined surgery and mortality rate. Even though LMCA

stenosis, NYHA

≥

III and EuroSCORE

≥

15 were associated

with early mortality in the univariate analysis, multivariate

logistic regression analysis revealed that the only risk factor

associated with surgical mortality was CBP time, as anticipated.

In other words, simple operations with shorter CPB times may

be more beneficial than better complex operations with longer

CPB times in high-risk patients.

In addition, our study findings confirmed that patients

undergoing combined surgery with concomitant CABG showed

lower long-term survival rates compared to surgical mortality

rates, from 16.7% post operatively to 13.3% long-term survival.

This is noticeably lower than the 24% early mortality that

was reported by Kolh

et al

.

18

Kurlansky

et al.

16

also identified

concomitant CABG as a predictor of mortality; however, they

showed the improvement in quality of life in the long term.

In our study, mitral valve surgery was associated with an

increased mortality rate (30.1%). This was consistent with a

number of previous studies.

15,19

It has been reported that AVR

can be performed in elderly patients with an acceptable mortality

rate, high long-term survival rate and functional improvement.

14,20

One-, three- and five-year survival rates were 76.2

±

4.12, 69.03

±

4.44 and 61.40

±

5.13%, respectively. However, these rates need

to be confirmed.

13,14

The low survival rates in our study can be attributed to

multiple factors, including that 87.7% of patients had extracardiac

co-morbidities; 10.5% had poor ejection fraction, and 86% were in

NYHA class

≥

III. Postoperative pacemaker, respiratory infection

and haemodialysis were predictors for late mortality, while aortic

cross-clamp time and CPB time were found with multivariate

analysis to be independent predictors of mortality. These results

suggest that combined surgery entails prolonged ischaemic time,

leading us to tailor an appropriate surgical strategy for each patient.

The use of bioprosthetic valves, which allow for implantation

of larger prostheses, was lower than in previous studies. The

early experiences of Peterseim

et al

.

21

reported that bioprostheses

should be considered in patients with a number of co-morbidities

or aged

≥

65 years. In a retrospective study, however, Silberman

et al

.

22

reported that the selection of valve replacement device

should be based on life expectancy, patient preference, lifestyle

and surgery-related complications.

The limitations of the present study include missing

information due to limited data collection, as it was a retrospective

study, and missed regular out-patient visits. Although 98.9% of

patients completed the follow-up period, less attention was paid

to the quality of life. Among long-term survivers, only two

patients had poor activity levels. However, the Short form 36

health survey should be completed for further investigation of

long-term quality of life.

Conclusion

It is obvious that we need more surgical experience on elderly

patients. Our study results demonstrate that an individually

tailored approach including scheduled surgery increased short-

and long-term outcomes of AVR in patients aged

≥

70 years.

In addition, shorter cardiopulmonary bypass time may be more

beneficial in this high-risk patient population.

Although several issues should be considered for elderly

patients undergoing cardiac surgery, including socio-economic

factors, the possible benefits of surgery should not be ignored

in patients with aortic valve disease who are eligible for surgery.

In addition, in the presence of combined cardiac procedures, a

hybrid approach or transcatheter aortic valve implantation with

isolated conventional AVR may be an alternative in high-risk

patients.

References

1.

HALE (healthy life expectancy 2000–2011) World Health Organization,

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/indhale/en.2.

Sedrakyan A, Vaccarino V, Paltiel AD, Elefteriades JA, Mattera JA,

Roumanis SA,

et al

. Age does not limit quality of life improvement in

cardiac valve surgery.

J Am Coll Cardiol

2003;

42

: 1208–1214.

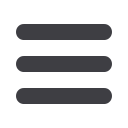

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

0

50 100 150 200 250

Follow up (month)

Probability of survival

Fig. 1.

Probability of survival.

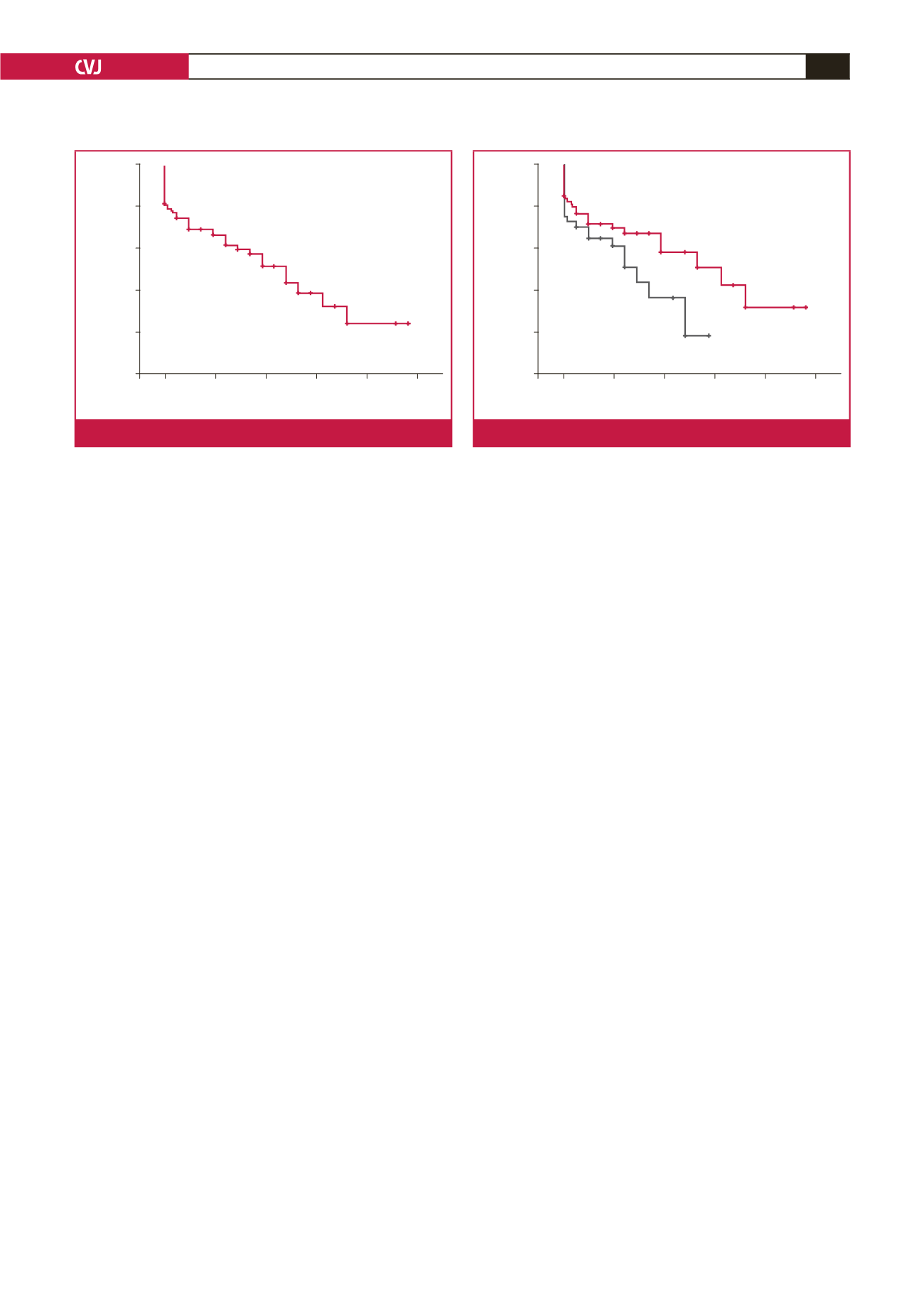

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

0

50 100 150 200 250

Follow up (month)

Probability of survival

Fig. 2.

Survival rates in the combined surgery group.