CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 25, No 5, September/October 2014

AFRICA

201

injection of 130 mg/kg of ketamine (Ketalar, Pfizer) and 20

mg/kg of xylasine (Rompun, Bayer). Sedation was maintained

with 50 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride so that the animals

remained under anaesthesia during blood collection and superior

mesenteric artery clamping.

Blood samples were obtained from the control group to

determine basal CNP levels. A simple laparotomy was performed

on the rats in groups I, II and III in order to clamp the superior

mesenteric artery (SMA) and artificially create mesenteric

ischaemia. The SMA remained clamped for three hours in group

I, six hours in group II, and nine hours in group III. Blood

samples were collected from the animals after the designated

duration of induced mesenteric ischaemia without declamping,

and then they were sacrificed. Several animals died during the

procedure, including one in group II and three in group III, and

they were subsequently excluded from the study. Plasma CNP

levels were measured from the collected blood samples.

Biochemical analysis was as follows. Blood collection tubes

containing citrate were used, and after the samples were obtained

they were centrifuged at 4 000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes. The

centrifuged samples were then transferred into Eppendorf tubes

for storage at –80°C.

Commercially available radioimmunoassay kits (RIA) (C-type

natriuretic peptide-22, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmount, CA,

USA) were used to determine plasma CNP levels. One millilitre

of plasma was eluted with a 1-ml volume of 60% acetonitrile

mixed in a 1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) solution for the solid-

phase extraction step, as previously described by del Ray

et al.

7

After the remaining product was dissolved in 300–500

μ

l of

assay buffer, 100

μ

l of the resulting mixture was used to perform

the immunometric assay.

7

The average CNP recovery was

calculated to be 74.8%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed with the SPSS software

(SPSS version 15.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL USA).

Data were expressed as the mean

±

one standard deviation (SD).

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess whether the

data conformed to a normal distribution. A

p

-value

<

0.05

was considered statistically significant. Significant differences

between group means were assessed with one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD)

was used as a

post hoc

test.

Results

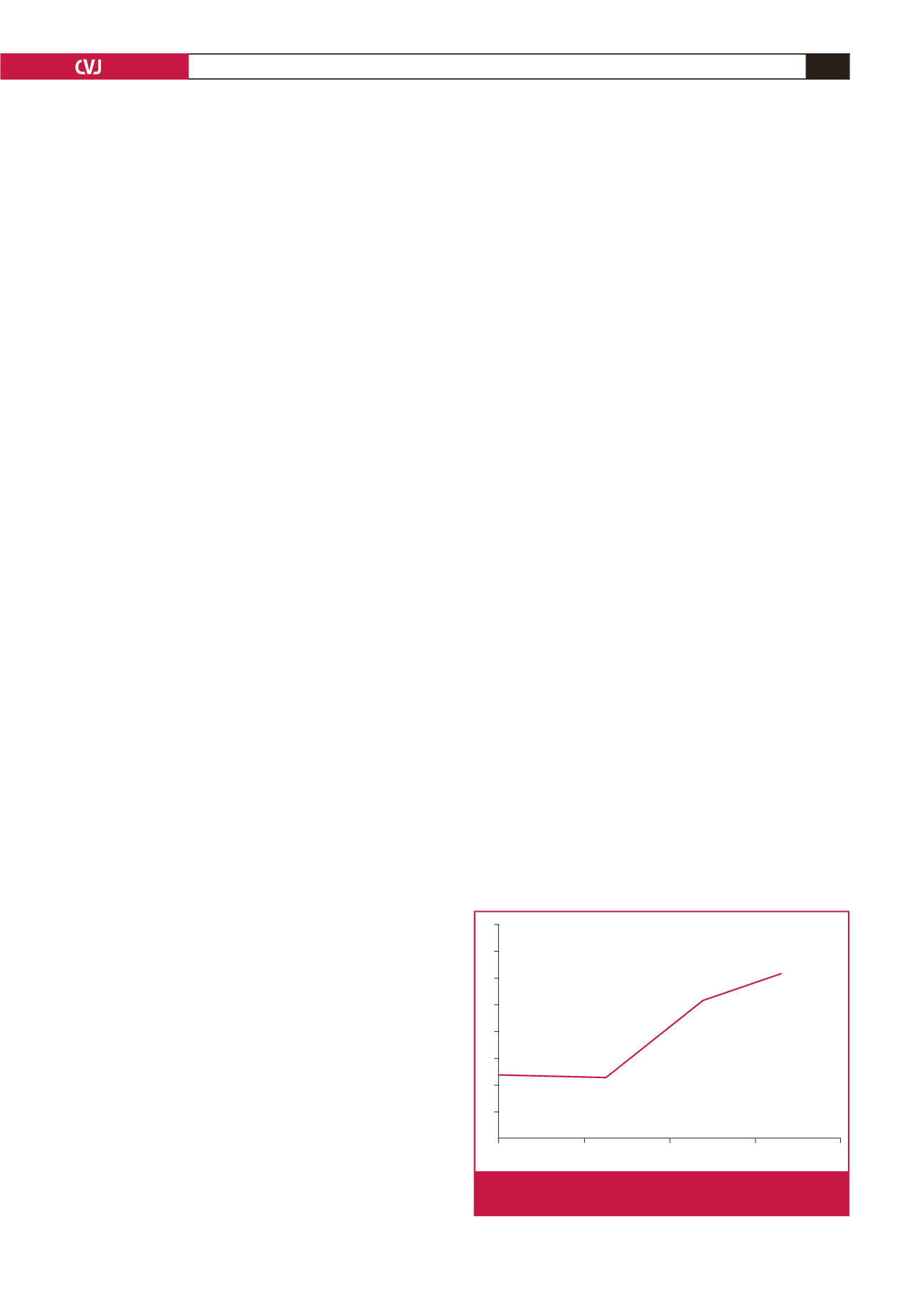

In the control group, the mean plasma CNP level was 2.54

±

0.42 pg/ml. A slight decrease in CNP level was observed in

group I relative to the controls following three hours of induced

mesenteric ischaemia [2.38

±

0.18 pg/ml (

p

=

0.085)]. However,

mean CNP levels were dramatically increased in group II (5.23

±

0.22 pg/ml) compared to the controls and group I following six

hours of mesenteric ischaemia (

p

=

0.001). Average CNP levels

were even higher in group III (6.19

±

0.67 pg/ml) relative to the

controls and group I (

p

=

0.000) and group II (

p

=

0.036).

There was a significant positive correlation between plasma

CNP levels and longer durations of induced mesenteric

ischaemia (

R

=

0.56,

p

<

0.001). The CNP levels observed in each

experimental group are summarised in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that plasma CNP levels were

relatively low during the initial stages of mesenteric ischaemia.

However, CNP levels quickly elevated in response to longer

durations of sustained ischaemic injury. These findings are

promising because CNP levels may allow one to differentiate

between early and late mesenteric ischaemia.

The initial reduction in CNP levels during the early hours

of mesenteric ischaemia may have been due to systemic CNP

regulatory pathways. On the other hand, elevated plasma CNP

levels during the sixth and ninth hours of induced mesenteric

ischaemia may signify delayed mesenteric endothelial resistance

or a response compounded by progressively worsening mesenteric

ischaemia.

CNP was first isolated from blood collected from the brain

and was subsequently categorised into the natriuretic peptide

family, which contains three molecules that have a particular

22-amino acid structure.

9

In later studies, it was reported that

CNP may also be isolated from plasma samples obtained from

the colon, lung, heart and kidneys.

9

CNP is a unique endogenous ligand for natriuretic peptide

B receptor (NPR-B) and is upregulated by transforming growth

factor-

β

, which is an important vascular remodelling factor.

9,10

NPR-B is located on vascular smooth muscle and modulates

vascular tone.

9,11

CNP inhibited proliferation of endothelial and vascular

smooth muscle cells in

in vitro

studies.

12

Additionally, CNP

demonstrated anti-atherogenic properties via p-selection

suppression, which regulates the recruitment of leukocytes and

platelet–leukocyte transmission.

12

It has been reported that CNP is released from endothelial

cells in rat mesenteric vessels and activates endothelium-derived

hyperpolarising factor (EDHF). EDHF then triggers potassium

channel opening and NPR-B activation so that mesenteric

vascular smooth muscle cells will hyperpolarise and relax.

13

Despite the important role that CNP plays in mesenteric vessel

tone, the effects of CNP have not been previously studied in the

setting of mesenteric ischaemia.

CNP produced anti-fibrotic and anti-proliferative effects via

inhibition of cultured fibroblasts, and reduced tissue growth

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Control

Group I

Group II

Group III

6.19

±

0.67 pg/ml

5.23

±

0.22 pg/ml

2.54

±

0.42 pg/ml

2.38

±

0.18 pg/ml

Fig. 1.

CNP levels according to duration of induced mesen-

teric ischaemia.