CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 4, July/August 2017

232

AFRICA

opportunity to better appreciate radiation doses and use of best

practices to reduce radiation among patients undergoing nuclear

cardiology procedures on the African continent, and how Africa

compares to the rest of the world in terms of patient dose and

best-practice adherence.

Analysis of data from INCAPS revealed that overall radiation

dose to patients undergoing a procedure in Africa was similar to

that among patients undergoing a procedure elsewhere in the

world. Notably, African laboratories performed much better

than the rest of the world with regard to best-practice adherence

to minimise patient dose, as reflected in both a higher QI score

and proportion of laboratories adhering to each best practice.

However significant variation in ED and QI score was noted

within Africa, specifically at the laboratory level.

The eight-fold range in median patient ED at the laboratory

level is likely attributable to protocol use, specifically the practice

of stress-only imaging. While this practice was used in the

majority of African laboratories, the rate of use was higher in

some than others. One laboratory in particular used a stress-only

protocol in 73% of its cases and had the lowest median ED, and

incidentally, the highest patient volume.

The option of stress-only protocol could be a consequence of

a few factors: the desire to lower radiation dose, the overload of

patients due to insufficient nuclear cardiology facilities inducing a

long waiting list, and/or for economic reasons to reduce the cost of

MPI. But regardless of the laboratory’s motivation to commonly

use a stress-only protocol, its salutary effect on radiation dose is

undeniable. By contrast, the laboratory with the highest mean ED

used a stress-only protocol in only 1.7% of cases.

However while a practice of stress-only imaging is desirable

where indicated, the correct rate is determined by the disease rate

in the imaged population. Therefore it is difficult to determine

the extent to which the observed rates of stress-only use reflect

over- or under-use of this protocol, or of MPI imaging more

generally.

Overall there was good adherence in the use of specified best

practices among the observed African laboratories. However,

in contrast with the results of the worldwide study, there is a

seemingly poor correlation between laboratory adherence to best

practices and mean patient ED in Africa. Surprisingly, the two

laboratories that adhered to all eight best practices were among

the laboratories with the highest patient ED on the continent.

These laboratories predominantly used two-day protocols, with

rest imaging performed on the second day, a fact that might

explain the relatively higher rates of stress-only use in these

laboratories (29.6 and 38.5%), compared to other observed

laboratories in INCAPS. This suggests that dose-minimisation

strategies are not strictly limited to the best practices described.

Likewise, adherence to a best practice as we have defined

it does not mean it is optimally applied in the laboratory.

For example, a laboratory might use a high-efficiency solid-

state SPECT camera for every case, but may never use prone

positioning (both camera-based dose-reduction strategies).

Laboratories should continue to be vigilant in ensuring that

patient doses are optimised, given the high doses involved in the

MPI study. Still, the lack of complete adherence to best practices

among the majority of laboratories suggests opportunity to

further reduce patient EDs through those practices specified

by the expert committee. Furthermore this should be possible

Table 3. African laboratory patient volume,

radiation exposure and quality index score

Laboratory

No of

patients

Effective dose (mSv) Quality index

(QI) score

25% Median 75%

Algeria 1

42

5

8.4

9.5

7

Algeria 2

73

1.8

2

6.2

7

Algeria 3

17

2.5

4.5

5.1

7

Algeria 4

14

11.3 11.9 12.5

6

Egypt 1

54

8.2 16.3 17.2

8

Egypt 2

39

7.3 15.3 16

8

Kenya 1

5

11.4 11.6 11.8

4

Senegal 1

4

6.3

8

8.9

5

South Africa 1

12

9.4

9.4

9.4

5

South Africa 2

60

14.8 16.1 17.8

6

Tunisia 1

21

8.2

9.4

9.9

7

Tunisia 2

7

3.1

3.6

9

6

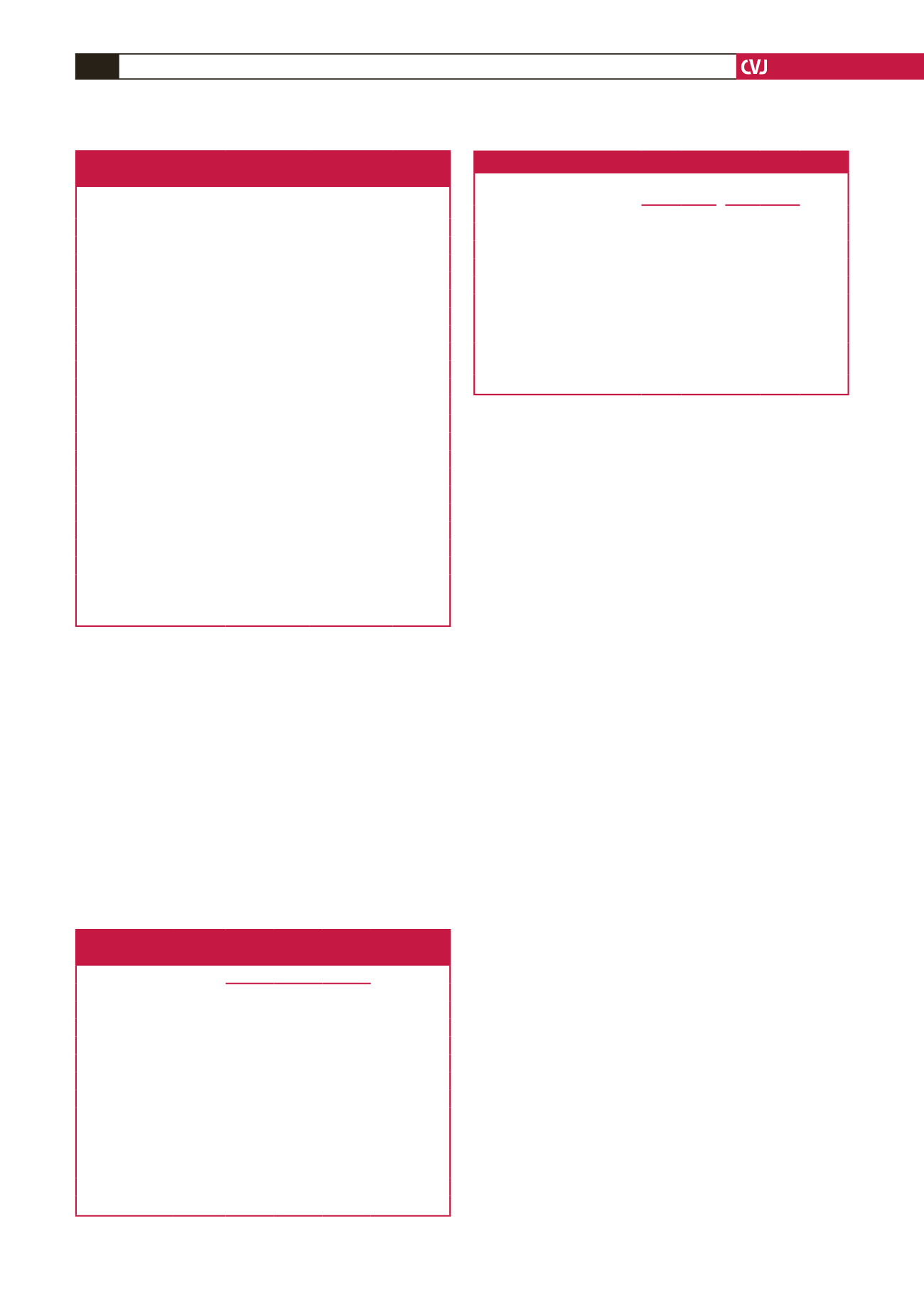

Table 4. Laboratory best-practice adherence

Best practice

Africa

(

n

=

12)

Rest of world

(

n

=

296)

p

-value

n

%

n

%

Avoid thallium stress

12 100.0 270 91.2 0.61

Avoid dual isotope

12 100.0 286 96.6 1

Avoid too much technetium 11 91.7 252 85.1 1

Avoid too much thallium 12 100.0 294 99.3 1

Perform stress-only imaging

8 66.7 85 28.7 0.005

Use camera-based dose-

reduction strategies

8 66.7 198 66.9 1

Weight-based dosing for

technetium

6 50.0 82 27.7 0.108

Avoid shine through

7 58.3 129 43.6 0.313

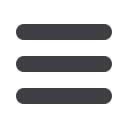

Table 2. Patient and laboratory demographics

and clinical characteristics

Patients

Africa

(

n

=

348)

Rest of world

(

n

=

7 563)

p

-value

Female,

n

(%)

135 (38.8)

3119 (41.2)

0.36

Age (years)

Mean

60.2

64.3

<

0.0001

SD

11

12

Effective dose (mSv)

Median

9.1

10.3

0.14

IQR

5.1–15.6

6.8–12.6

Range

1.8–20.0

0.75–35.6

≤

9 mSv,

n

(%)

173 (49.7)

2892 (38.2)

<

0.001

Stress-only,

n

(%)

109 (31.3)

896 (11.8)

<

0.001

PET,

n

(%)

6 (1.7)

465 (6.1)

<

0.001

Laboratories

12

296

Patients/laboratories

Median

19

16

0.402

IQR

10–48

8–33

Range

4–73

1–250

Quality index score

≥

6,

n

(%)

9 (75.0)

133 (44.9)

0.041

Mean

6.3

5.4

0.013

SD

1.2

1.3

Laboratories with median

dose

≤

9 mSv,

n

(%)

5 (41.7)

86 (29.1)

0.35

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.