CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 6, November/December 2017

e2

AFRICA

A two- and three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardio-

gram (2D/3D TEE) was done to further define this lesion. In this

patient, poor transoesophageal views prevented a full assessment

of the pathology. There was a likely SA aneurysm with orifice

located below the non-coronary and left coronary cusps (NCC/

LCC). The aortic leaflets and the root were normal. There was

retraction of the aortic leaflets and impingement of the LA,

the right pulmonary artery, and possibly the right ventricular

outflow tract (RVOT) by the aneurysm. There were no associated

thrombi, vegetations or other congenital lesions.

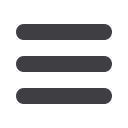

Due to suboptimal imaging on TTE and TEE, a cardiac MRI

was requested to confirm the SA aneurysm and to define with

certainty its relationship to the surrounding structures (Fig. 2).

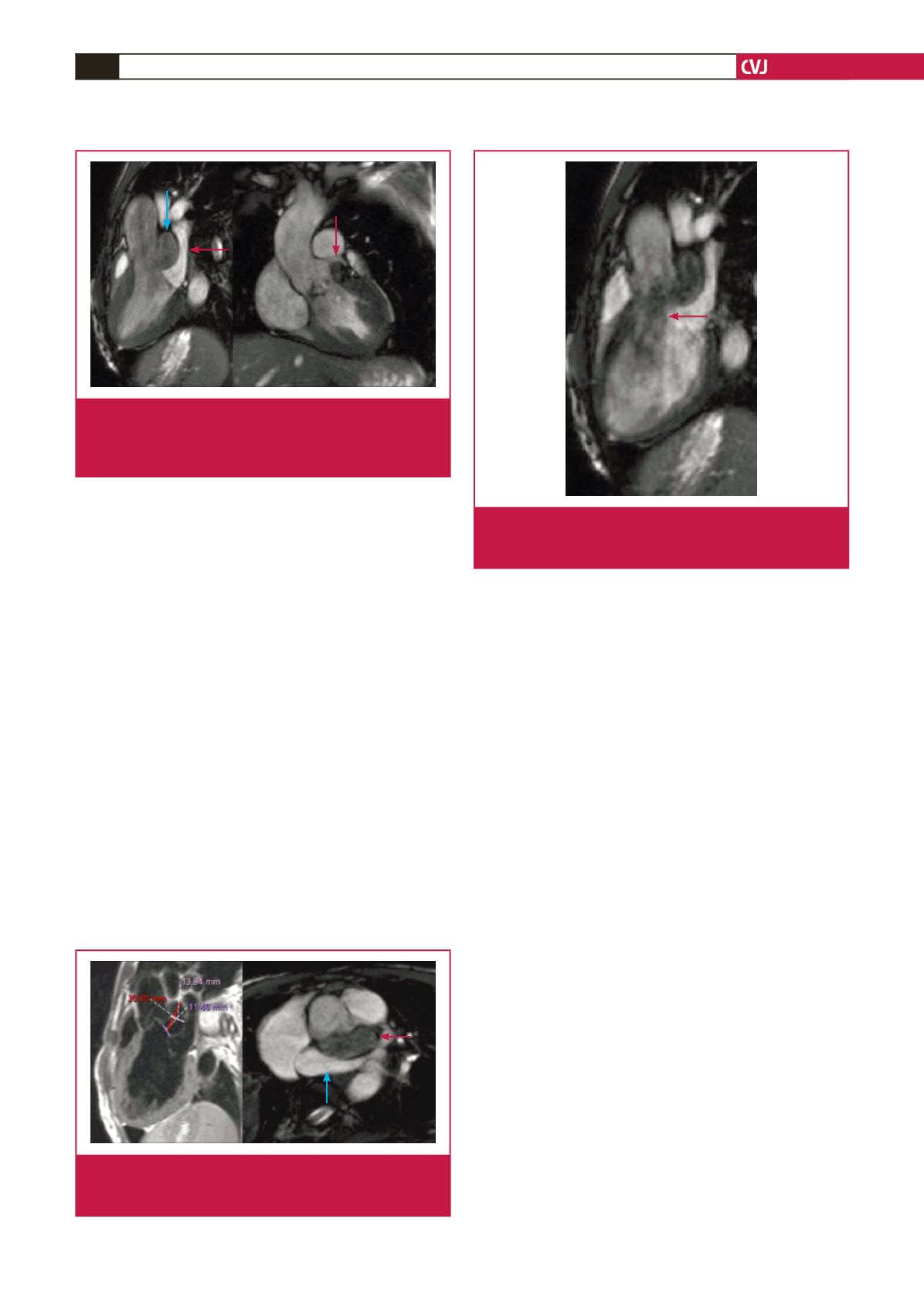

A 30 × 14-mm aneurysm with a 12-mm neck was noted below

the aortic valve, which extended to the LA roof (Fig. 3). The

communication point was just below the LCC. AR of moderate

severity was noted (Fig. 4).

Discussion

SA aneurysms are rare and postulated to be the result of a

defect of congenital origin between the valvular annuli and

the ventricular wall.

1

Other possible aetiologies, although not

confirmed, include tuberculosis, syphilis, rheumatic fever and

infective endocarditis.

3,4

Whether HIV has a causal connection

also remains to be proven. These infections may merely represent

an association, given their high prevalence, and causality cannot

be inferred.

5

SA aneurysms are rarer than sub-mitral aneurysms and the

diagnosis is more challenging.

1,2,6

They are mostly not suspected

clinically and are found coincidentally on imaging.

7

The chest

X-ray was normal in this patient, unlike with sub-mitral

aneurysms where an enlarged cardiac silhouette is often noted.

3

SA aneurysms need to be differentiated from more commonly

occurring aneurysms such as sinus of Valsalva aneurysms, which

are located above the aortic valve.

6

SA aneurysms mostly occur in young Africans.

6

The origin

is usually below the left coronary cusp, as in our patient.

2,6

Clinical presentation varies, ranging from cardiac failure and

systemic emboli (due to aneurysmal thrombi) to angina (due to

coronary artery compression or emboli), and dysrhythmias such

as ventricular tachycardia.

1

A lack of aortic cusp support and

distortion of the annulus is responsible for AR and subsequent

cardiac failure.

3

The most widely available imaging tool is TTE but this may

be inadequate, as smaller aneurysms may be missed, especially in

patients with suboptimal imaging windows. The diagnosis is also

dependent on the skill and knowledge of the operator.

7

Cardiac MRI is increasingly becoming a complimentary

tool to echocardiography in assessing valves and congenital

lesions.

8

In patients with inadequate echocardiographic imaging,

cardiac MRI allows a detailed assessment of the anatomy of

congenital lesions such as SA aneurysms, and their relationship

to the surrounding structures. Additionally, MRI allows accurate

quantification of AR severity.

Cardiac MRI in our case allowed the precise localisation of

the lesion below the LCC, which proved difficult on TTE and

2D TEE. Furthermore, involvement of the RVOT, which was

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular outflow tract (left) and short-axis views

(right) depicting compression of the left atrium (blue

arrow) by the sub-aortic aneurysm (red arrow).

Fig. 2.

Left ventricular outflow tract views showing the sub-

aortic aneurysm (blue arrow) compressing the left

atrium (red arrow, left) and sparing the left coronary

artery (right).

Fig. 4.

Left ventricular outflow tract MRI image showing an

aortic regurgitant jet (arrow) secondary to retraction

of the left coronary cusp by the sub-aortic aneurysm.