CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 1, January/February 2019

AFRICA

53

University ethics review committee. Data used in this study were

obtained from patient charts routinely collected at the clinic, and

a written informed consent was provided before screening by

each participant while attending the HIV clinic. Confidentiality,

anonymity and privacy of all participants were guaranteed at

all levels of this study by excluding all unique identifiers for the

participants.

Baseline assessment included demographic variables, risk

factors for CVD and measurement of body mass index (BMI),

blood pressure, non-fasting total cholesterol and random blood

glucose levels. World Health Organisation (WHO) cardiovascular

risk score was calculated for patients aged above 40 years

8

and

the information included in the patients’ medical record files. All

people with HIV attending the Ukwala HIV clinic were included.

Those who declined consent for the cardiovascular risk-factor

screening and pregnant women were excluded.

Patients fulfilling national eligibility criteria (CD4 count

>

350

cells/mm

3

at time of the study) were treated with standard ART

according to national guidelines.

9

Standard regimens at that

time included tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz (TNF/3TC/

EFV) or zidovudine, lamivudine and efavirenz (AZT/3TC/EFV).

Some were still receiving stavudine, lamivudine and efavirenz

(D4T/3TC/EFV), which was being phased out at the time.

A minority received a lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r)-containing

regimen.

Prior to commencing CVD screening within the HIV clinics

at Ukwala sub-county hospital, healthcare providers (including

nurses, laboratory technologists, clinicians and data clerks) in the

health facility received a two-day training, followed by regular

intensive theoretical and practical skills training and mentoring

in measuring and interpreting cardiovascular risk factors. The

facility was also provided with regularly calibrated point-of-care

diagnostic equipment for cardiovascular risk assessment.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured using a hospital-grade

Omron M3

®

(Omron, Netherlands) digital automatic blood

pressure machine. Hypertension diagnosis was based on

standard guidelines, and included blood pressure measurements,

medical history, physical examination, assessment of absolute

cardiovascular risks (where deemed necessary by the examining

physician) and laboratory investigations. A comprehensive

assessment of BP involved multiple measurements taken on

separate occasions, at least twice or three times, one or more

weeks apart or sooner if the hypertension was severe.

Hypertension was defined as per the seventh report of the

Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation

and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7)

10

as follows:

pre-hypertension: systolic 120–139 mmHg, diastolic 80–89 mmHg;

stage 1 hypertension: systolic 140–159 mmHg, diastolic 90–99

mmHg; stage 2 hypertension: systolic

≥

160 mmHg, diastolic

≥

100

mmHg, and those currently on antihypertensive drugs.

Total cholesterol and blood glucose levels were measured in

the clinic using finger-prick blood by a Humansence

®

(Human,

Wiesbaden, Germany) meter calibrated with a control strip on the

first and after every 10th specimen. Raised total cholesterol level

was defined according to US National Cholesterol Education

Program ATP III guidelines.

11

Data collection involved the extraction of data from the

patients’ charts using a standardised data tool by trained data

clerks. Charts for patients who attended the clinic from June

2013 to January 2015 were targeted. Those with missing details

on key variables such as cardiovascular risk-factor screening

results and ART regimen were excluded from the data.

Detailed abstraction was then conducted on the remaining

patients’ charts using a data tool that was made up of four

sections, including: (1) anthropometric measures (age, body mass

index, waist circumference and blood pressure), (2) behavioural

and biomedical cardiovascular risk factors (including smoking

status, excessive use of alcohol and non-fasting total cholesterol

level), (3) clinical information (such as on HIV infection and

HIV treatment, ART regimen and duration), and (4) medical

history. Data extracted were entered in a paper data tool then

later transferred into an EpiData software version 3.1 for clean-

up in readiness for analysis using SPSS software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version

22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive

statistics involved calculating the median and interquartile range

(IQR) for continuous data and proportions for categorical

variables. Comparisons of median duration between groups

were done using the Mann–Whitney test with a 5% level

of significance. Associations were assessed using a logistic

regression model, and crude and adjusted odds ratios are

reported with their corresponding confidence intervals.

Results

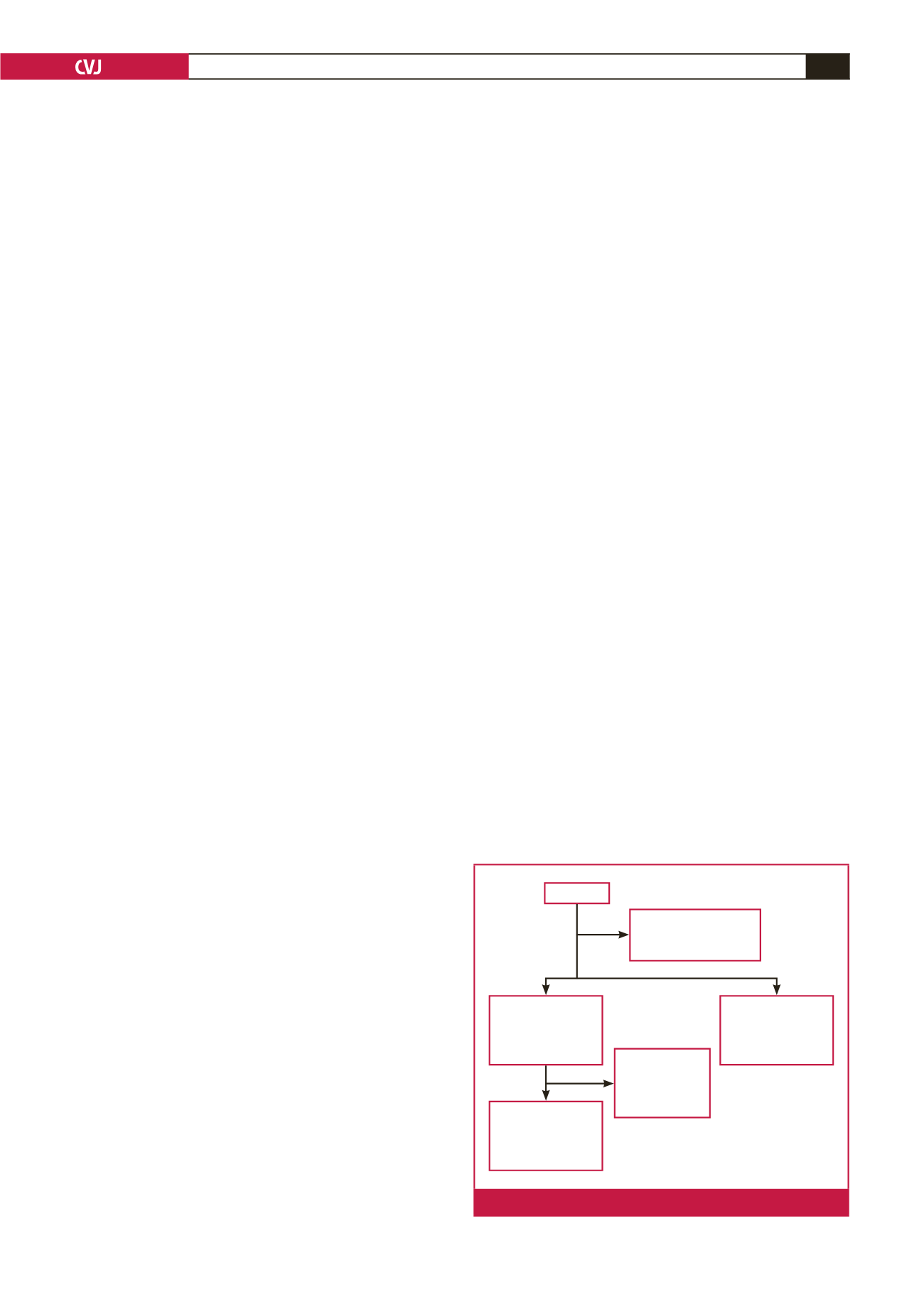

A total of 1 510 subjects was screened, of whom eight were

excluded from analysis because of incomplete data (Fig. 1). Data

collected included demographic variables, risk factors for CVD

and determination of BMI, measurement of blood pressure, and

non-fasting total cholesterol and random blood glucose levels.

Cardiovascular risk score was calculated for those above 40 years

using the WHO (Afri-E) risk-screening chart.

8

Of the subjects screened, 69% (1 036) were women. The

median age was 30 (IQR 31–48) years and median CD4 count

was 430 (IQR 308–574) cells/mm

3

; 79% of subjects were on ART

with a documented regimen. Current smokers were 1.9% (29),

n

=

1 510

n

=

8

with incomplete initial

CVD screening

n

=

1 217

On ART

at initial CVD

screening

n

=

1 181

with complete

information on

ART regimen

n

=

36

Missing

information on

ART regimen

n

=

285

Pre-ART

Had not yet started

ART at initial CVD

screening

Fig. 1.

Data flow chart for cardiovascular risk screening.