CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 3, May/June 2019

164

AFRICA

There was no significant difference between the two groups in

terms of location, length or diameter of the target lesion, except

that the emergency PCI group had a higher rate of thrombus-

containing lesions (

p

=

0.028). The number of patients with

an initial TIMI 3 flow was similar in the two groups (43.24 vs

58.14%,

p

=

0.493).

All patients underwent angiography and stent implantation.

A significantly higher procedural success rate was achieved in the

delayed PCI group, with a 97.7% success rate, compared to an

86.3% success rate in the emergency PCI group (

p

=

0.007). This

higher procedural success rate was related to a remarkably lower

rate of no re-flow or slow flow (2.3 vs 13.7%,

p

=

0.007) during

PCI. Consequently, TIMI 3 flow was observed significantly more

frequently at the end of the procedure in the delayed PCI group

compared with the immediate PCI group (100 vs 86.3%,

p

<

0.001) (Table 3).

There was one death in the emergency PCI group due to cardiac

rupture, and two other deaths in the delayed PCI group; one

patient died of cardiac arrest and the other of cardiogenic shock.

No difference was found in in-hospital mortality rates between

the two groups (1.4 vs

2.3%,

p

=

0.562). There was no significant

difference in rate of MACE between patients who had received

emergency PCI and those in whom PCI was delayed (16.4 vs 9.3%,

p

=

0.133). The left ventricular ejection fraction was similar in the

two groups at the time of discharge, and was an average of 52%.

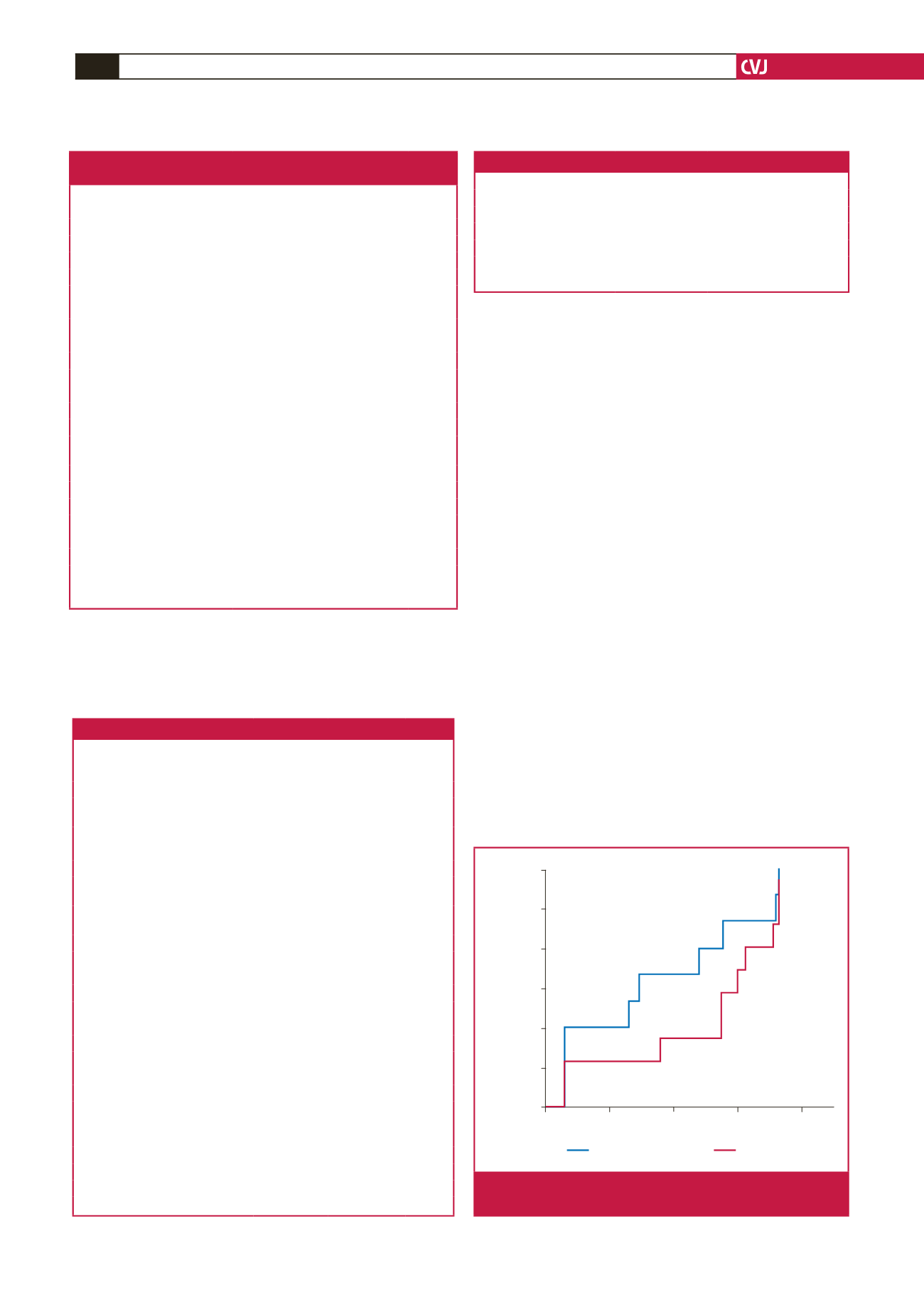

Information on one year of follow up was collected for the

remaining 156 patients. The left ventricular ejection fraction was

similar in the two groups [median 58% (57–68) in the emergency

PCI group vs median 56% (50–62) in the delayed PCI group,

p

=

0.666]. Although the emergency PCI group had a trend towards

a higher rate of MACE, the difference was not statistically

significant [12.2 vs

11.6%, hazard ratio (HR)

=

1.067, 95% CI:

0.434–2.627,

p

=

0.887] (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics in the emergency PCI

and the delayed PCI groups

Emergency PCI

Delayed PCI

p-

value

(

n

=

73)

(

n

=

86)

Age (year)

62.31

±

13.40

63.08

±

12.85 0.714

Gender (male),

n

(%)

60 (82.19)

65 (75.58)

0.338

Hypertension,

n

(%)

40 (54.79)

41 (47.67)

0.427

Diabetes,

n

(%)

17 (23.28)

26 (30.23)

0.37

Dyslipidaemia,

n

(%)

10 (13.7)

5 (5.81)

0.11

Smoking,

n

(%)

38 (52.05)

44 (51.16)

1.00

SBP (mmHg)

141.31

±

27.40

130

±

23.16

0.052

DBP (mmHg)

81.22

±

16.59

74.44

±

13.50 0.218

Pulse (bpm)

79.61

±

15.27

81.41

±

20.25

0.74

hs-CRP,

n

(median) (mmol/l)

6.58 (0.48–114.7) 9.87 (0.42–68.77) 0.022*

Peak CK-MB,

n

(median) (U/l)

63 (6–544)

37 (6–546)

0.10

Creatine,

n

(median) (µmol/l)

83 (36–188)

81 (46–378)

0.921

Uric acid (mmol/l)

372.49

±

102.05 355.88

±

118.06 0.293

Fasting glucose,

n

(median)

(mmol/l)

5.6 (3.86–17.56) 5.96 (3.81–23.11) 0.038*

LDL-C,

n

(median) (mmol/l)

2.96 (0.99–6.05)

2.7 (1.23–6.46)

0.4

Serum potassium (mmol/l)

3.88

±

0.38

3.94

±

0.46

0.386

Killip 1,

n

(%)

58 (79.45%)

71 (82.56%)

0.686

Anterior wall infarction,

n

(%)

51 (69.86%)

52 (60.46%)

0.246

Time from onset to admission (h)

24 (12–72)

26.5 (12–72)

0.012*

Time from onset to PCI (h)

24 (12–72)

192 (20–480)

<

0.001*

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; hs-CRP: high-sensi-

tivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LVEF: left

ventricular ejection fraction; *

p

<

0.05.

Table 2. Baseline angiographic and procedural data in the two groups

Emergency

PCI

(

n

=

73)

Delayed

PCI

(

n

=

86)

p-

value

Symptoms pre-PCI,

n

(%)

Most recent chest pain within 12

hours of admission

27 (36.9)

16 (18.6)

0.012*

Antiplatelet therapy,

n

(%)

Loading dose of aspirin

73 (100)

86 (100)

1.00

Loading dose of clopidogrel

73 (100)

86 (100)

1.00

Routine dose of aspirin > 1 day

pre-PCI

8 (10.9)

81 (94.2)

<

0.001*

Routine dose of clopidogrel

> 1 day pre- PCI

0 (0)

81 (94.2)

<

0.001*

Other antithrombotic therapy,

n

(%)

Thrombolytic therapy before PCI

0 (0)

3 (34.9)

0.25

GPIIb/IIIa pre-PCI

18 (24.6)

4 (4.7)

<

0.001*

LMWH use pre-PCI

6 (8.2)

86 (100)

<

0.001*

IRA lesion site,

n

(%)

0.099

Right coronary artery

15 (20.5)

30 (34.9)

Left anterior descending

52 (71.2)

47 (54.7)

Circumflex artery

7 (9.6)

9 (10.5)

Characteristics of the target lesion

Length of target lesion (mm)

24 (14–69)

30 (12–72)

0.063

Diameter of target lesion (mm)

3.25 (2.3–4.0) 3.14 (2.25–4.0)

0.24

Stenosis degree of target lesion

(median) (%)

99 (80–99)

95 (70–99)

0.001*

Thrombus-containing lesion,

n

(%)

17 (23.3)

8 (9.3)

0.027*

TIMI flow degree,

n

(%)

Initial TIMI 3 flow

32 (43.8)

50 (58.1)

0.081

IRA: infarct related artery. *

p

<

0.05.

Table 3. Final angiographic and procedural data after PCI

Emergency PCI

Delayed PCI

p-

value

(

n

=

73)

(

n

=

86)

PCI,

n

(%)

73 (100)

86 (100)

1

Final TIMI 3,

n

(%)

63 (86.3)

86 (100)

<

0.001

Slow flow/no re-flow,

n

(%)

10 (13.7)

2 (2.3)

0.007

Procedure success rate,

n

(%)

63 (86.3)

84 (97.7)

0.007

*

p

<

0.05

Days

Emergency group

Delayed group

0

100

200

300

400

Rate of MACE

0.12

0.10

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0.00

11.6%

12.2%

Fig. 2.

MACE during one year of follow up in emergency

versus delayed PCI group.