CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 21, No 2, March/April 2010

AFRICA

95

heart rates, and SBP and DBP at rest (Table 2). G2 patients had a

higher mean duration of diabetes than G1 (69.0

±

9.48 vs 18.7

±

8.7 months;

p

=

0.007). The patients’ characteristics at rest were

not statistically significantly different (Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, peak systolic blood pressure was signifi-

cantly higher in G2 subjects than in G1 (213.6

±

20.1 vs 200.0

±

15.3 mmHg;

p

=

0.04). The difference between resting systolic

and peak systolic blood pressure (

Δ

SBP) as well as resting pulse

pressure and pulse pressure during exercise (

Δ

PP) followed a

similar trend to that of peak systolic blood pressure. Exercise

capacity in G2 subjects was significantly lower than in G1 by

12.94% (7.4

±

1.1 vs 8.5

±

1.5 METs;

p

=

0.042). Although, there

was no statistically significant difference between the LV mass

index in the two groups, G2 subjects had significantly higher

relative wall thicknesses than those in G1 (0.53

±

0.03 vs 0.41

±

0.04;

p

<

0.001) (Table 4).

Discussion

The relationship of blood pressure response to exercise and end-

organ damage in hypertensive subjects is not clear. Studies on

this subject in diabetics are few, especially among blacks, who

unfortunately are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular-

related complications than their Caucasian counterparts.

15

This

study is the first in Nigeria to assess the relationship between

blood pressure response to exercise and abnormal LV geometry.

In this study, gender, age and BMI were comparable among

the patients with normal LV geometry and those with LV concen-

tric remodelling. The longer duration of diabetes in patients with

concentric LV remodelling supports the earlier assertion that

the longer the duration of diabetes, the more the likelihood that

the patient will develop cardiovascular complications. This was

despite the fact that short-term (FBG, two-hour post-prandial

blood glucose) glycaemic control was similar in both groups

in this study, suggesting that blood pressure response during

exercise may not have been much influenced by blood glucose

exposure.

It has been suggested that blood pressure response may be

related to blood glucose control.

16

Marfella

et al

. reported that

in the resting state, the presence of hyperglycaemia led to an

increase in SBP and DBP independently of endogenous insulin

in 20 patients with type 2 diabetes. A reduced availability of

nitric oxide was suggested as a possible explanation.

16

In our study, the peak systolic blood pressure during exercise

was significantly higher in patients with LV concentric remodel-

ling than in those with normal LV geometry. This however was

not the case with peak diastolic blood pressure. This was reflect-

ed in the significant change in pulse pressure (

Δ

PP) observed

during exercise. Pulse pressure provides a crude guide to stiff-

ness of the large conduit arteries.

17

Physiological parameters

related to blood pressure regulation and potential contributors to

reduced exercise capacity in type 2 diabetic individuals include

reduced LV systolic volume, altered myocardial and diastolic

functions and increased arterial stiffness.

5,18

The elevated peak

exercise SBP observed in patients with concentric left ventricular

remodelling in this study was probably partly associated with

arterial stiffness, as reflected by the higher

Δ

PP.

5,6

Exercise capacity was also reduced in patients with LV

concentric hypertrophy in our study. This may provide addi-

tional explanation for reduced exercise tolerance in normoten-

sive diabetes patients. It has been suggested that the voltage

on the ECG of left ventricular hypertrophy may be an early

marker of impaired exercise capacity.

19

Previous studies have

shown that left ventricular hypertrophy independently predicted

reduced exercise capacity.

20

This study has shown that type 2

diabetic patients with increased peak systolic blood pressure had

increased arterial stiffness, higher LVMI, abnormal LV geometry

and reduced exercise capacity.

Conclusion

Normotensive diabetics with concentric left ventricular remodel-

ling have increased systolic blood pressure reactivity to exercise.

It is probable, as suggested in earlier studies, that increased blood

pressure reactivity to exercise is an indicator of target-organ

damage, especially in normotensive diabetics.

References

Gottdierer JS, Brown J, Zoltick J, Fletcher RD. Left ventricular hyper-

1.

trophy in men with normal blood pressure: relation to exaggerated blood

pressure response to exercise.

Ann Intern Med

1990;

112

: 161–166.

Al’Absi M, Devereux RB, Lewis CE,

2.

et al

. Blood pressure responses to

acute stress and left ventricular mass.

Am J Cardiol

2002;

89

: 536–540.

Rostrup M, Smith G, Bjo¨ rnstad H, Westheim A, Stokland O, Eide

3.

I. Left ventricular mass and cardiovascular reactivity in young men.

Hypertension

1994;

23

(Suppl I): I168–I171.

Stewart KJ, Sung J, Silber HA,

4.

et al

. Exaggerated exercise blood

pressure is related to impaired endothelial vasodilator function.

Am J

Hypertens

2004;

17

(4): 314–320.

Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M,

5.

et al

. Impact of diabetes on

cardiac structure and function: the Strong Heart Study.

Circulation

2000;

101

: 2271–2276.

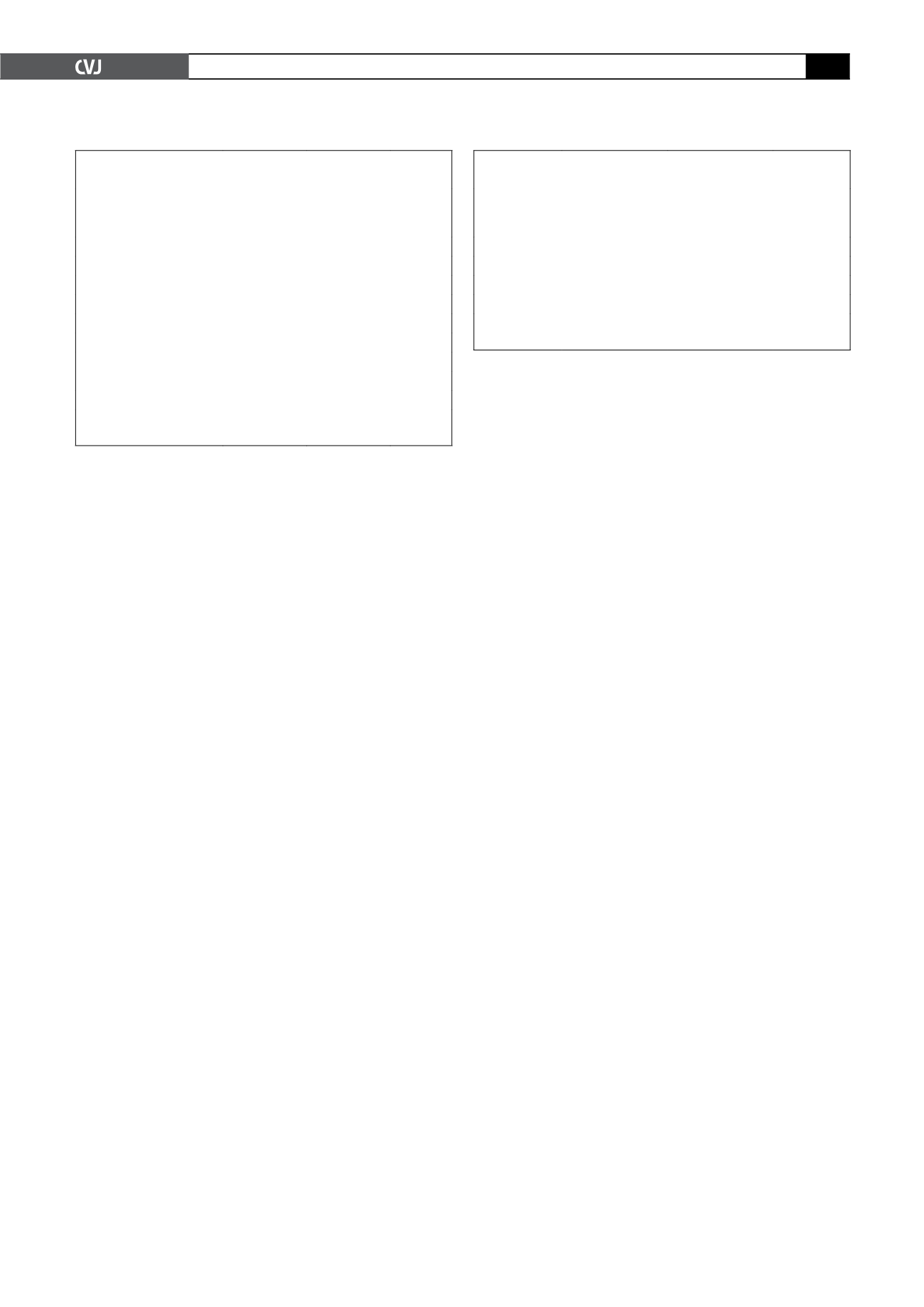

TABLE 3. EXERCISE-INDUCED HAEMODYNAMIC

FACTORS

Parameters

Normal LV

geometry

(

n

=

19)

Concentric

LV remodel-

ling (

n

=

11)

p-value

(Student’s

t-test)

pHR (bpm)

167.8

±

10.9 162.8

±

21.7 0.405

pDBP (mmHg)

94.2

±

7.7 98.2

±

11.7 0.270

pSBP (mmHg)

200.0

±

15.3 213.6

±

20.1

0.045

Δ

HR (bpm)

75.7

±

18.4 72.7

±

28.1 0.725

Δ

DBP (mmHg)

21.5

±

14.1 24.0

±

13.3 0.596

Δ

SBP (mmHg)

81.5

±

14.1 98.9

±

20.1 0.010

Δ

PP (mmHg)

105.8

±

9.6 115.5

±

11.3 0.019

HR reserve

0.97

±

0.16 0.87

±

0.03 0.222

Exercise capacity (METs)

8.5

±

1.5

7.4

±

1.1 0.042

Statistical significance at

p

<

0.05

Values are expressed as mean

±

SD.

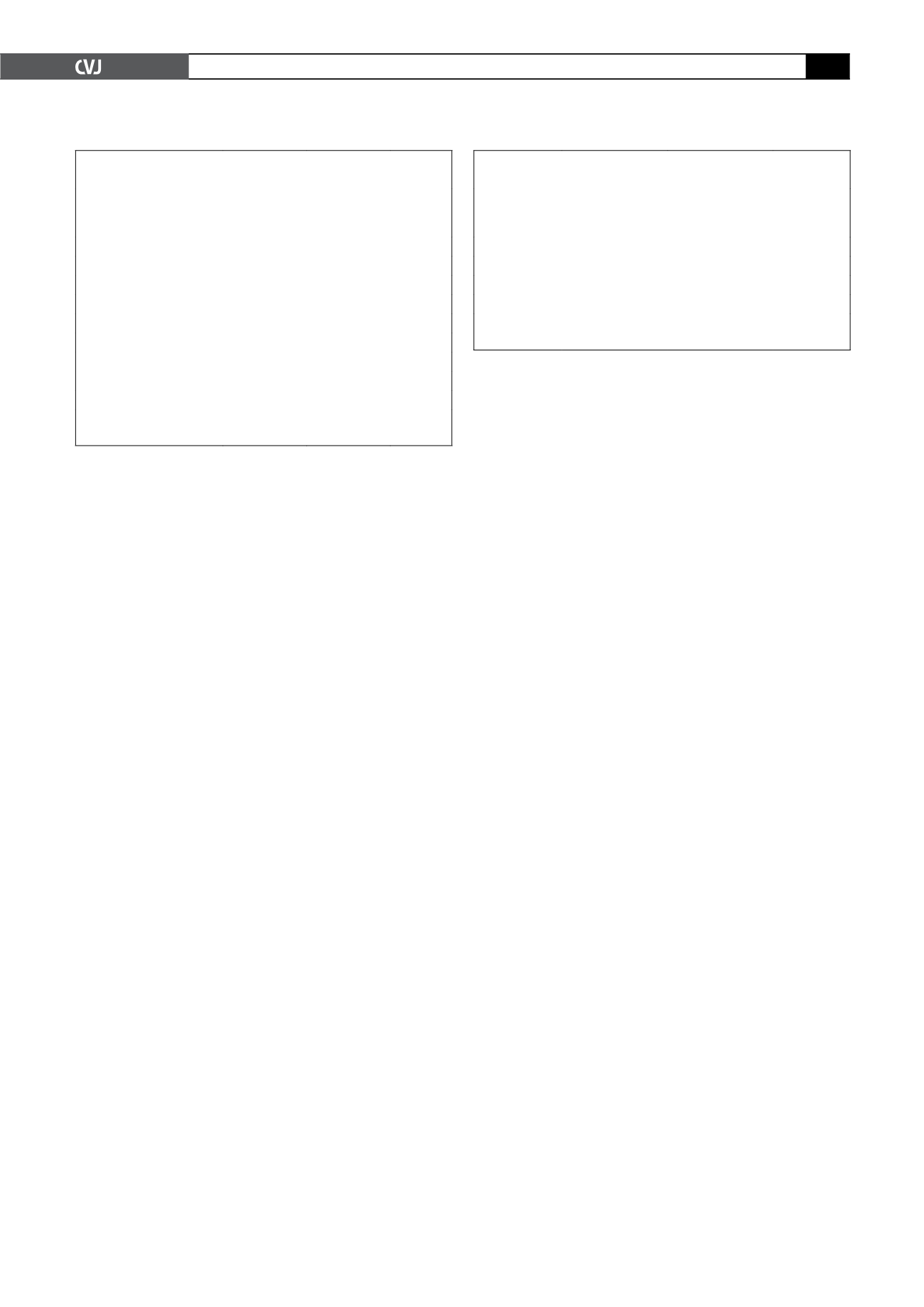

TABLE 4. ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC PARAMETERS OF G1

AND G2 SUBJECTS

Parameters

Normal

LV geometry

(

n

=

19)

Concentric

LV remodelling

(

n

=

11)

p

-value

(Student’s

t-test)

LVMI (g/m

2

)

81.1

±

13.4

88.9

±

21.8

0.233

IVST (mm)

9.8

±

1.2

11.1

±

1.3

0.010

PWT (mm)

9.0

±

1.3

10.9

±

1.1

<

0.001

RWT

0.41

±

0.04

0.53

±

0.03

<

0.001

Statistical significance at

p

<

0.05

Values are expressed as mean

±

SD.