CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 3, May/June 2018

178

AFRICA

of care. To complement our quantitative evaluation of current

ACS care at Kenyatta National Hospital, we also conducted

a prospective qualitative analysis to understand facilitators of,

barriers to and the context of in-hospital ACS care. We sought to

identify knowledge, attitude and behaviour about interventions

for improvement of quality of healthcare through in-depth

interviews with healthcare providers involved in the management

of ACS patients at Kenyatta National Hospital. This qualitative

evaluation will provide informative data for future activities to

improve quality of care in the hospital and region.

Methods

This qualitative study included in-depth interviews of key

participants who were healthcare providers involved in the

management of ACS patients at Kenyatta National Hospital,

which is one of the two main public referral centres in Kenya. The

hospital has Kenya’s most advanced diagnostic and management

capabilities for ACS care, including having the only public

cardiac catheterisation laboratory in the country.

We developed interview guides to explore facilitators of,

barriers to and context of in-hospital ACS care at Kenyatta

National Hospital. We modelled this qualitative study based

on our team’s prior research in India, which has led to the

development of a theoretical model that viewed ACS care

through a patient-orientated process map including five stages:

(1) prior to first medical contact, (2) at the point of first medical

contact, (3) early hospitalisation, (4) mid-to-late hospitalisation,

and (5) at the point of discharge.

4

Starting in January 2017, we selected an initial sample

of hospital leaders for interviewing and used a snowballing

technique to identify additional participants during February

2017. We used the principle of maximal variability sampling to

seek new participants to achieve a diverse sample. We continued

our recruitment until we achieved saturation of major themes

identified during our analysis.

All interviews with audio recordings were conducted by one

interviewer (EB) in English and lasted between 36 and 65 minutes.

Audio transcripts and interview field notes of the first three

transcripts were independently coded by two individuals (EB,

SV) to develop a comprehensive codebook. The same coders used

Dedoose version 7.5.27

5

to code the remaining transcripts and field

notes using the codebook. We also developed and implemented

a brief survey to capture demographic data and open-ended

responses regarding facilitators of, barriers to and context of ACS

care, which were further explored in the in-depth interviews.

The study was approved by the University of Washington

institutional review board, the Kenyatta National Hospital/

University of Nairobi ethics and research committee and

Northwestern University institutional review board. Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

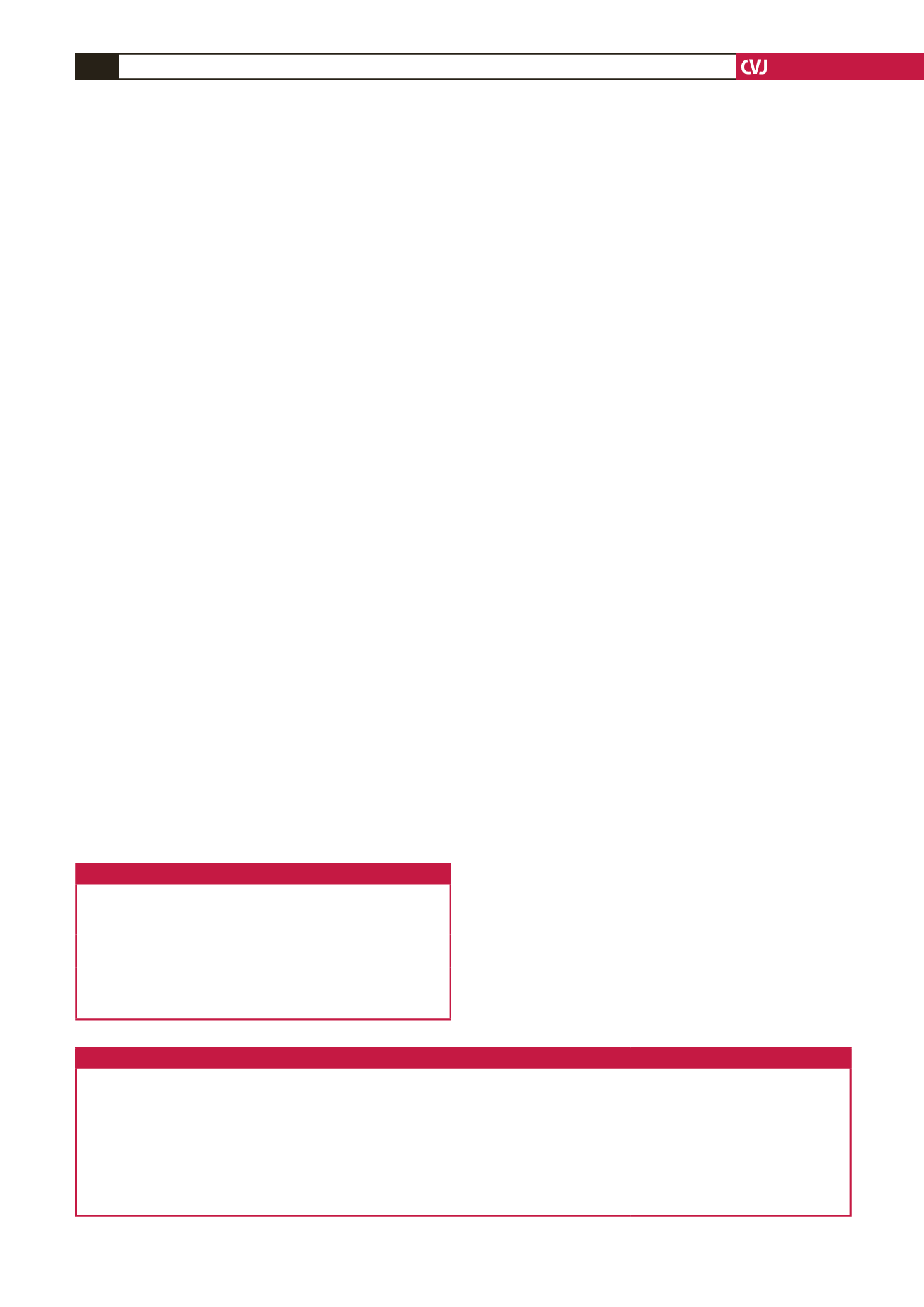

We conducted 16 interviews during the study period, including

with one cardiologist, two accident and emergency (A&E)

attending physicians, two medical officers in the casualty

department, three A&E nurses, and eight medical registrars

(Table 1). More than half (56%) of the interviewees were women.

We also provide a summary of the major facilitators of and

barriers to ACS care at Kenyatta National Hospital that were

highlighted by most participants in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Theme 1: There is a significant delay from onset

of patient symptoms to presentation at Kenyatta

National Hospital

All participants explained that there is a significant delay from

symptom onset to presentation at Kenyatta National Hospital,

which seems largely driven by a lack of patient understanding of

ACS symptoms that warrant emergent medical attention. This

delay is further exacerbated by the inter-hospital transfer system

from district hospitals to Kenyatta National Hospital.

‘Of course, from the patient side, delay is a big problem and

therefore once they come late we end up doing heart-failure

management post MI, many of our people do not have the

knowledge that if I have a chest pain, I need to rush to

hospital…So, knowledge in our community is an area that

we need to educate the community about chest pain’

Other respondents described patients seeking care at pharmacies

rather than hospitals, for initial management.

‘Significant delay in presentation from symptom onset

because most of the time most Kenyans usually try and

buy over-the-counter medications and don’t present unless

the pain is severe.’

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics

Participants

Number = 16 (%)

Type of ACS provider

Cardiologist

1 (6)

A&E room attendants

2 (13)

A&E room medical officers

2 (13)

Nurses

3 (19)

Medical residents

8 (50)

Female

9 (56)

Table 2. Facilitators of in-hospital ACS management at Kenyatta National Hospital

Hospital level

Provider level

• The hospital is one of a few institutions that has diagnostics including ECG and echocardiography, and is the only

public hospital with a cardiac catheterisation laboratory, although availability of some of these diagnostic services

are limited and could be improved

• Guideline-directed in-patient and discharge. Medical therapy, specifically antiplatelet agents, beta-blockers, statins,

anticoagulants and ACE inhibitors are largely available

• Hospital-fee waiver for certain services is available for patients who are unable to afford emergency medical treatment

• The hospital has critical care units, both in the casualty department and medical wards, to take care of critically ill

patients, including ACS patients

• Structured follow-up mechanism post discharge through the cardiology clinic

• Continuing medical education programmes that cover current ACS treatment guidelines

• Availability of expert staff including cardi-

ologists, well-trained critical-care nursing

staff and medical registrars

• Well-trained echocardiography technicians

• Providers that participated in this qualita-

tive research displayed great interest in

improving existing ACS care, including

potential quality improvement