CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 5, September/October 2018

308

AFRICA

useful in outcome measures.

Inazumi

et al

. found that cystatin C levels were more accurate

for mortality prediction than eGFR in patients with ADHF.

23

They showed that even without a decrease in eGFR, increases

in cystatin C level were associated lower long-term, event-free

survival (180 days). Also, Rafouli-Stergiou

et al

. reported

that in-hospital rise in cystatin C and NT-proBNP levels was

useful in predicting 60-day cardiac death and rehospitalisation.

24

Similarly, we found that, rather than estimated GFR calculations,

in-hospital mortality rate was related to higher cystatin C and

NT-proBNP levels. However, during long-term follow up, only

sodium level was an independent predictor of death, which

affirms that hyponatraemia is a surrogate marker for mortality.

25

Interestingly, we found that younger patients were more

prone to suffer a cardiac death than older subjects. The possible

reason for this finding may be that our hospital is a tertiary

referral centre for heart transplant candidates, and younger

patients with a worse clinical condition are mostly referred to

our centre for advanced therapies. When we looked at similar

studies evaluating mortality differences in ADHF patients, they

principally included older subjects (60 years or more),

11,23,24

with

an absence of younger patients, which might have limited data on

differences in mortality rates in such patients.

Compared to the above studies, including younger patients

may add further information about the association between

cystatin C levels and mortality rates in such populations.

Furthermore, among patients who died during their hospital

stay, the rate of prior cerebrovascular accident was significantly

higher than among survivors. The presence of cerebrovascular

accident is a risk factor for HF,

26

but the co-existence of these

conditions may be related to increased mortality rate.

In the ASCEND trial, 180-day follow up of patients with

ADHF showed that baseline cystatin C level was a strong

predictor of adverse events.

27

However, increase in cystatin

C levels did not predict adverse outcomes. In contrast to the

ASCEND trial, we did not observe differences in mortality rate

with regard to baseline cystatin C levels during the 36-month

follow-up time. Despite the fact that the sample size of our study

was small, our results provide complementary data for long-term

follow up of subjects with ADHF and raised cystatin C levels.

Although our study had a prospective design and followed

patients for a considerable period, the number of recruitedpatients

was relatively small, which probably lowered the statistical power

of the study. Also, the recruited patients represent a relatively

young population compared to previous studies. Because our

centre is a tertiary referral hospital, the patient characteristics

may not represent the whole HF population. Finally, we

did not analyse GFR, cystatin C and plasma NT-proBNP

levels according to heart failure aetiology, and only admission

levels were evaluated rather than follow-up values. The cost-

effectiveness of serial measurements of cystatin C levels in the

prognostication of HF patients should be confirmed in large

prospective studies.

Conclusion

In subjects with ADHF, evaluation of admission cystatin C levels

may provide a reliable prediction of death compared to eGFR or

NT-proBNP levels. Higher cystatin C levels provided important

prognostic data about unfavourable in-hospital outcomes. For

the post-discharge follow-up period, sodium level was the marker

that had prognostic significance.

The preliminary results of this study (in-hospital mortality) were accepted as

an oral presentation at the American College of Cardiology congress in 2013

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.06.088). The three-year follow-up

results were accepted as an abstract presentation at the European Society of

Cardiology Heart Failure congress (21–24 May 2016) in Florence, Italy.

References

1.

Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney

disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitaliza-

tion.

N Engl J Med

2004;

351

: 1296–1305.

2.

Dharnidharka VR, Kwon C, Stevens G. Serum cystatin C is superior to

serum creatinine as a marker of kidney function: a meta-analysis.

Am J

Kidney Dis

2002;

40

: 221–226.

3.

Taub PR, Borden KC, Fard A, Maisel A. Role of biomarkers in the

diagnosis and prognosis of acute kidney injury inpatients with cardiore-

nal syndrome.

Expert Rev CardiovascTher

2012;

10

: 657–667.

4.

Lassus J, Harjola VP. Cystatin C: a step forward in assessing kidney

function and cardiovascular risk.

Heart Fail Rev

2012;

17

: 251–261.

5.

GarcíaAcuña JM, González-Babarro E, Grigorian Shamagian L, Peña-

Gil C, Vidal Pérez R, López-Lago AM,

et al

. Cystatin C provides more

information than other renal function parameters for stratifying risk

in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Rev Esp Cardiol

2009;

62

:

510–519.

6.

Naruse H, Ishii J, Kawai T, Hattori K, Ishikawa M, Okumura M,

et al

.

Cystatin C in acute heart failure without advanced renal impairment.

Am J Med

2009;

122

: 566–573.

7.

Dupont M, Wu Y, Hazen SL, Tang WH. Cystatin C identifies patients

with stable chronic heart failure at increased risk for adverse cardiovas-

cular events.

Circ Heart Fail

2012;

5

: 602–609.

8.

Bruneau BG, Piazza LA, de Bold AJ. BNP gene expression is specifically

modulated by stretch and ET-1 in a new model of isolated rat atria.

Am

J Physiol

1997;

273

: H2678–2686.

9.

Gustafsson F, Steensgaard-Hansen F, Badskjaer J, Poulsen AH, Corell

P, Hildebrandt P. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of N-terminal

ProBNP in primary care patients with suspected heart failure.

J Card

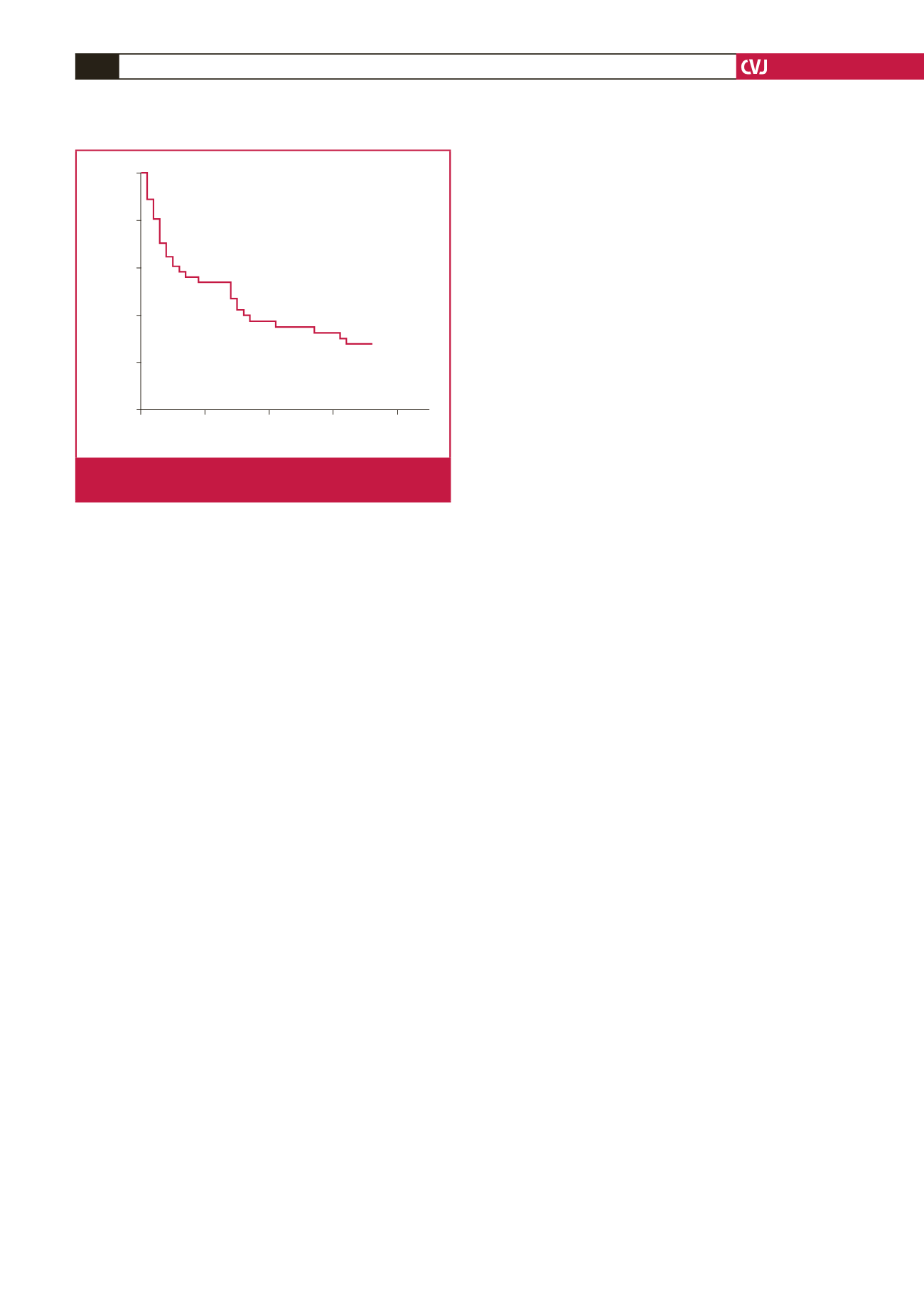

Months

0

10

20

30

40

Cumulative survival

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Fig. 1.

Plot of the survival curve for patients with acutely

decompensated heart failure.