CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 6, November/December 2019

334

AFRICA

The 2018 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the

European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery (EACTS)

published guidelines on myocardial revascularisation. They

recommended revascularisation in patients with stable angina

or silent ischaemia with a large area of ischaemia, defined as

ischaemia exceeding 10% of the left ventricular myocardium

as detected by functional testing, as a class I recommendation,

level of evidence B.

11

In these guidelines, the recommendation to

revascularise based on viability imaging is not stated.

In our study, more than half of the patients referred for

viability imaging had potentially reversible myocardial contractile

dysfunction (viability

>

10%). The decision to use 10% as a

cut-off point was informed by findings by Ling

et al

., who found

that revascularisation of patients with hibernating myocardium

that exceeded 10% of the total myocardium was associated with

increased survival, mainly if revascularisation was performed not

later than 92 days after PET imaging.

12

Different study designs and variable interpretation of

perfusion–metabolism images have resulted in conflicting

study outcomes that have caused controversy surrounding the

clinical utility of myocardial viability imaging. For example,

the sub-study of the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart

Failure (STICH) trial failed to show a survival benefit in patients

referred for viability imaging prior to revascularisation. In this

trial, participants were referred for viability imaging with SPECT

and dobutamine stress echocardiography. These modalities have

been reported to have a lower diagnostic accuracy for detecting

myocardial viability when compared to F18-FDG PET.

13

In our study, there were two clinical variables found in the

multivariable regression analysis to be significantly associated

with myocardial viability. Patients on aspirin therapy were

twice as likely to have viable segments. In a meta-analysis

evaluating the benefit and risk of low-dose aspirin in patients

with stable cardiovascular diseases, aspirin was associated with

a 21% reduction in the risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction,

non-fatal stroke and cardiovascular death.

14

The anti-platelet

effect of aspirin in culprit vessel lesions most likely improves

myocardial perfusion and therefore viability.

Hypertension was another clinical variable significantly

associated with myocardial viability. In a recent prospective

study evaluating the role of F18-FDG PET in the assessment

of myocardial viability involving 120 patients with myocardial

contractile dysfunction, Srivatsava

et al

. reported a higher

number of infarcted segments in hypertensive patients (

p

=

0.0005).

15

This is in contrast to our study findings, where

hypertensive patients were almost twice as likely to have viable

segments compared to patients without hypertension. We were

unable to find a plausible explanation for this association.

All challenges and limitations associated with retrospective

analysis of data apply in this study. Other relevant clinical

parameters such as atrial fibrillation, high sensitivity C-reactive

protein and a lipid profile were not available. Despite these

limitations, our pilot study demonstrates that in the clinical

management of patients with ischaemic heart disease referred

for PET evaluation, there is a cohort of patients with hibernating

or viable myocardium. Whether the clinical utility of PET has

a significant impact on cardiovascular outcomes remains to be

evaluated.

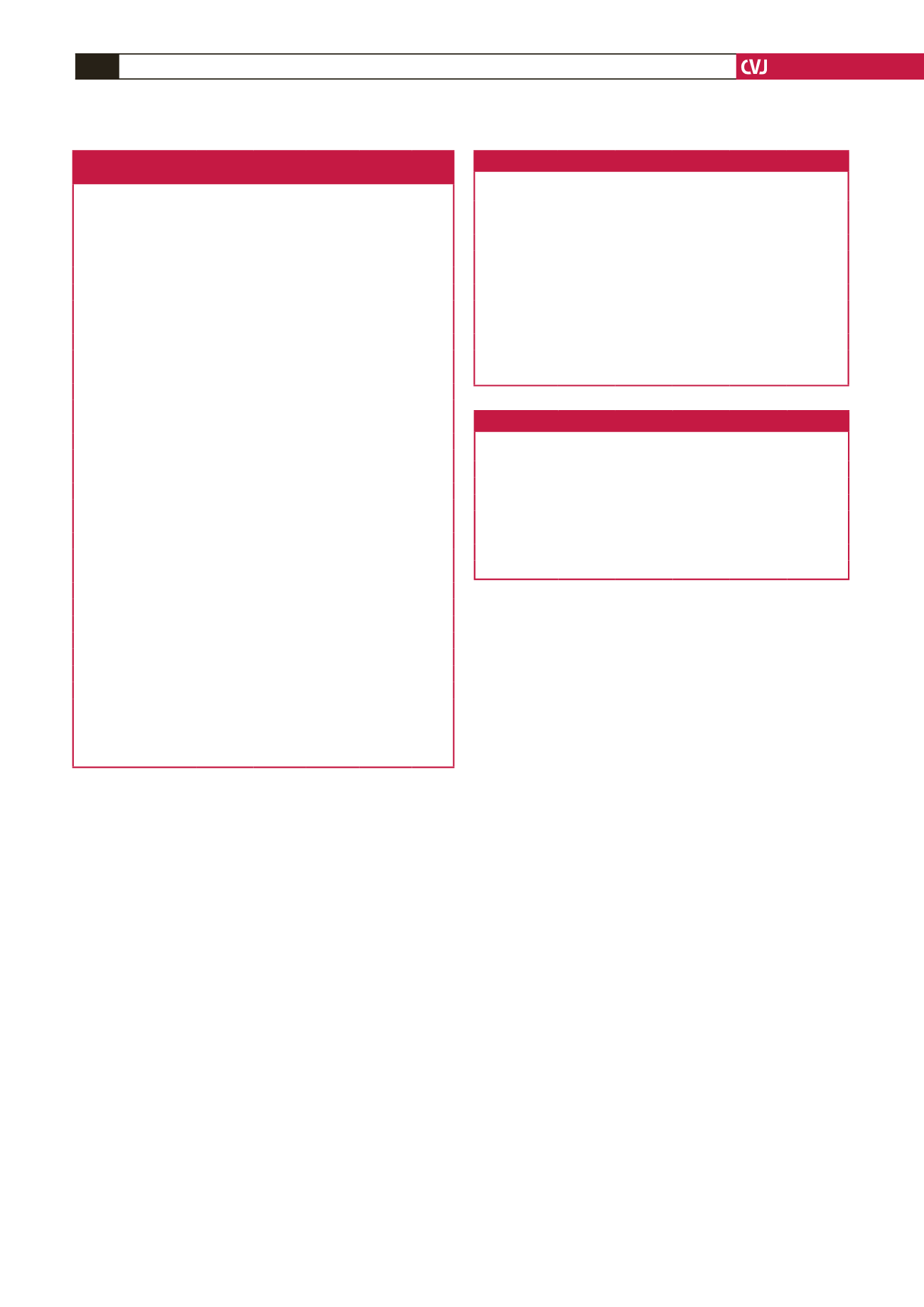

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

according to myocardial viability

Variable

Overall

population

(

n

=

236)

No viabil-

ity, 0%

(

n

=

91)

(38.6%)

Viability,

1

–

10%

(

n

=

14)

(5.9%)

Viability,

>

10%

(

n

=

131)

(55.5%)

p

-value

Male,

n

(%)

196 (83.1) 75 (82.4) 11 (78.6)

107

(81.7)

0.613

Ethnicity,

n

(%)

0.156

Caucasian

125 (53.0) 56 (61.5) 7 (50.0) 62 (47.3)

Indian

71 (30.1) 21 (23.1) 7 (50.0) 43 (32.8)

Black

32 (13.6) 12 (13.2) 0 (0.0)

20 (15.3)

CV risk factors,

n

(%)

Hypertension

115 (48.7) 33 (36.3) 10 (71.4) 72 (55.0) 0.005

Diabetes mellitus

62 (26.3) 17 (18.7) 5 (35.7) 40 (30.5) 0.101

Dyslipidaemia

93 (39.4) 29 (31.9) 11 (78.6) 53 (40.5) 0.004

Smoking

93 (39.4) 35 (38.5) 8 (57.1) 50 (38.2) 0.375

Family history

59 (25.0) 17 (18.7) 6 (42.9) 36 (27.5) 0.093

HIV

4 (1.7)

2 (2.2)

0 (0.0)

2 (1.5)

0.818

Medication,

n

(%)

Beta-blocker

108 (45.8) 31 (34.1) 6 (42.9) 71 (54.2) 0.012

Aspirin

104 (44.1) 29 (31.9) 8 (57.1) 67 (51.2) 0.010

Statin

100 (42.4) 29 (31.9) 8 (57.1) 63 (48.1) 0.028

ACE inhibitor

81 (34.3) 26 (28.6) 5 (35.7) 50 (38.2) 0.332

Ca

2+

antagonists

65 (27.5) 20 (22.0) 1 (7.1)

44 (33.6) 0.035

Nitrates

46 (19.5) 14 (15.4) 4 (28.6) 28 (21.4) 0.366

Wall motion,

n

(%)

Akinesia

65 (27.5) 29 (31.9) 2 (14.3) 34 (26.0) 0.324

Dyskinesia

80 (33.9) 24 (26.4) 5 (35.7) 51 (38.9) 0.149

Global hypokinesia

124 (52.5) 49 (53.9) 9 (64.3) 66 (50.4) 0.582

LVEF (SPECT),

n

(%)

Preserved (≥ 50%)

15 (6.4)

4 (4.4)

3 (21.4)

8 (6.1)

0.027

Mid-range (40–49%)

32 (13.6) 6 (6.6)

2 (14.3) 24 (18.3)

Reduced (

<

40%)

183 (77.5) 77 (84.6) 9 (64.3) 97 (74.1)

Data are shown as absolute numbers and (percentage) for categorical variables.

CV: cardiovascular; CAD: coronary artery disease; HIV: human immunodefi-

ciency virus; Ca

2+

: calcium; ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; SPECT: single-

photon emission computed tomography; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

Family history refers to history of any cardiovascular disease.

Table 2. Univariable logistic regression

Odds ratio Std error

z

p

-value

Confidence

interval

LVEF ≤ 39% 2.25

1.98

0.93

0.354 0.40–12.6

LVEF 40–49% 6.00

5.74

1.87

0.061 0.92–39.2

LVEF ≥ 50% 2.29

2.30

0.82

0.413 0.32–16.5

Dyskinesia

1.67

0.47

1.82

0.069 0.96–2.91

Hypertension

1.76

0.47

2.13

0.033 1.04–2.96

Aspirin

1.92

0.52

2.43

0.015 1.13–3.26

Male

0.98

0.33

–0.04

0.964 0.51–1.92

Diabetes

1.68

0.51

1.65

0.098

0.91–3.02

Dyslipidaemia

1.10

0.30

0.37

0.712 0.65–1.87

Smoking

0.89

0.24

–0.43

0.664 0.52–1.50

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; std error: standard error.

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression

Odds ratio Std error

z

p

-value

Confidence

interval

LVEF ≤ 39% 1.90

1.70

0.71

0.478 0.33–11.0

LVEF 40–49% 4.90

4.91

1.58

0.113 0.68–34.9

LVEF ≥ 50% 3.87

4.13

1.27

0.205 0.48–31.3

Dyskinesia

1.66

0.51

1.64

0.102 0.90–3.04

Hypertension

1.89

0.55

2.19

0.029 1.07–3.33

Aspirin

1.92

0.56

2.23

0.026 1.08–3.41

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; Std error: standard error.