CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 2, March 2013

AFRICA

39

plasma triglyceride levels pre-HAART and prior to developing

AIDS.

48

Both traditional and non-traditional risk factors therefore

appear to contribute to atherosclerotic disease in HIV-infected

patients. Those on HAART, particularly protease inhibitors,

develop a myriad of class- and non-class-specific metabolic

effects on lipid profiles, glucose levels, insulin sensitivity and

anthropometric body changes characteristic of lipodystrophy.

Untreated HIV infection may also have a paradoxical overall

effect on cardiovascular disease and thereby reduce the risk of

ischaemic heart disease because of severe and progressive weight

loss, wasting syndrome, hypotension resulting from chronic

gastroenteritis, hypoadrenalism and shortened life expectancy

associated with advanced AIDS.

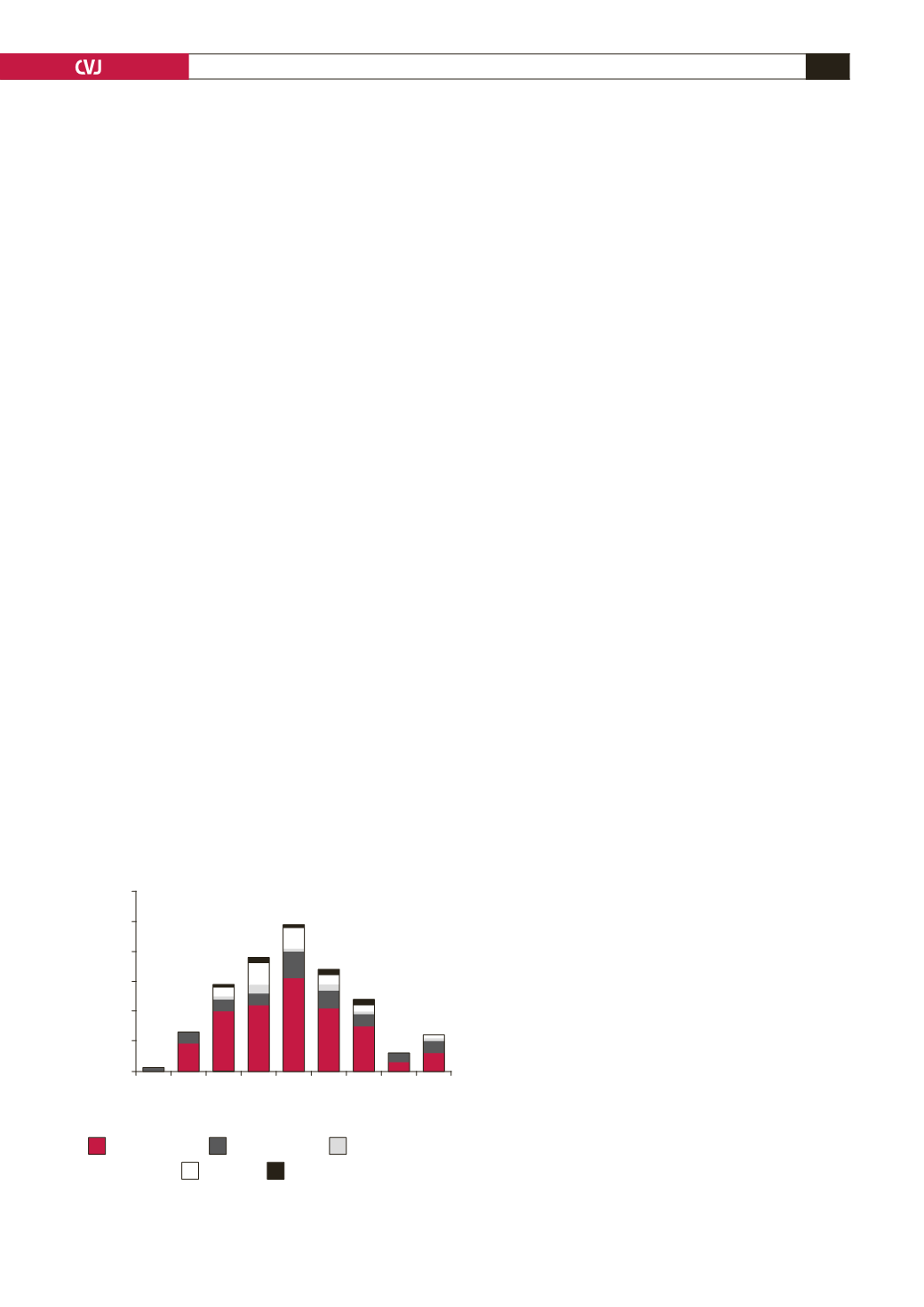

Despite the scarcity of data from SSA, there are some

indications of overall excess CVD risk factors in HIV-infected

patients. Situation analysis in 2008 of 501 HIV-infected patients

from Botswana using the database of the Botswana Medical Aid

Scheme combined with data from the Centre for Chronic Diseases

revealed impressive clustering of hypertension, dyslipidaemia,

obesity, dysglycaemia and smoking (Fig. 2). The peak age range

for the occurrence of CVD risk factors was about a decade after

the peak age for HIV infection in Botswana.

Given the difficulty of determining whether the observed

increase in CVD risks were due to HIV itself, treatment with

HAART or merely a factor of improved longevity, it would be

ideal to perform case–control studies on the prevalence of CVD

risk factors and the prevalence of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular

endpoints such as IHD, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease in

HIV-infected versus age- and gender-matched non-HIV-infected

individuals. Also, a comparison of pre-HAART and on-HAART

HIV-infected patients would shed light on this grey area. It

is important to remember that the enormous impact of HIV/

AIDS does not appear to have diminished the impact of chronic

cardiovascular diseases on mortality in SSA.

49

Reports on IHD in SSA

There are a few scattered reports of IHD in SSA. Kengne and

colleagues

50

collated a total of 356 cases of SSA patients with

coronary heart disease (CHD) from four selected countries

(Ghana, Cameroon, Senegal and Kenya). They reported a high

prevalence of CHD risk factors, which was not surprising in this

selected population of patients with established CHD. Males

outnumbered females by ratios ranging from 1.3:1 to 6:1, with

hypertension in up to two-thirds of the patients. The report

highlighted the fact that IHD was by no means rare in these

African populations.

The African arm of the INTERHEART study showed

that dyslipidaemia, abdominal obesity and tobacco use

accounted for greater population-attributable risk in the overall

African population, whereas hypertension and diabetes were

less prominent risk factors.

51

However, in black Africans,

dyslipidaemia was followed by hypertension, abdominal obesity,

diabetes and then tobacco use.

The INTERHEART African study cast doubt on the notion

of protective lipid profiles in blacks, as one reason for implicitly

low IHD prevalence in Africa. High HDL cholesterol levels in

black Africans might be dysfunctional and less protective than

generally believed. However, the findings of the INTERHEART

African study were at slight variance with reports by Ezzati and

colleagues who showed that hypertension, low intake of fruits

and vegetables and physical inactivity accounted for population-

attributable fractions for ischaemic heart disease mortality of

43, 25 and 20%, respectively, in the Africa region. These were

all above the population-attributable fraction of 15% for high

cholesterol.

52

Limitations in diagnostic evaluation of patients with possible

IHD might explain, at least in part, the apparent rarity of IHD in

SSA. This is illustrated by the study on black South Africans by

Joubert and colleagues using data from the Medical University of

South Africa (MEDUNSA) stroke data bank. The study showed

increased prevalence of CHD with improved diagnostic tools.

53

History of angina pectoris or myocardial infarction using

the Rose questionnaire yielded a prevalence of only 0.7% in

741 black patients with stroke, 71% of whom had cerebral

infarction. Resting 12-lead electrocardiography was analysed for

the presence of poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads,

the presence of pathological Q waves and ST–T wave changes

using the Minnesota code in 555 stroke patients, 72% of whom

had cerebral infarctions confirmed on computed tomography.

Ninety-three of the 555 patients (16.8%) had evidence of

coronary artery disease, of whom 81 had features of myocardial

ischaemia, eight had pathological Q waves and four patients had

features of acute myocardial infarction. There has been long-

standing controversy regarding ECG diagnosis of myocardial

ischaemia in black Africans.

53-57

Ignoring ECG features of ‘ischaemia’ and ascribing such

changes to ‘normal variation’ poses the potential danger of

under-diagnosis or misdiagnosis of myocardial ischaemia in

black Africans. Rather, future work should attempt to unravel

the genetic mechanisms behind abnormal ECG patterns in black

Africans.

The combination of clinical assessment, chest radiograph,

resting electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography and

MUGA scanning showed features of CHD in 18 patients

(17.6%) in the MEDUNSA study. Scintigraphy with or without

dipyridamole infusion in 60 stroke patients in this study revealed

features of coronary heart disease in 45% of the patients.

Macroscopic and microscopic pathological examinations of the

Fig. 2. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in HIV-infected

patients in Botswana.

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

<30 30–34 35–39 40–44 45–49 50–54 55–59 60–64 65+

Number of affected HIV patients

Hypertension

Disglycaemia

Dyslipidaemia

Obesity

Smoking

Source: BOMAID/CCD database, 2008 (total of 501 HIV infected patients)

Age range (years)