CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 24, No 4, May 2013

AFRICA

125

Other factors which have been identified include: the level

of education and training of health workers and/or people with

ARF/RHD who may not fully understand the role of secondary

prophylaxis in preventing ARF and subsequent heart damage;

refusal by some people who do not want to receive treatment

despite their level of understanding; difficulties accessing

healthcare, that is, travelling to the health facility to receive

treatment may be difficult and/or costly, especially for people

living in rural and remote areas; forgetting to attend the health

centre on the date when secondary prophylaxis is due; staff

workloads and priorities. Healthcare staff may be unable to

identify and encourage people who do not receive regular

secondary prophylaxis.

11,12

In Uganda, RHD is the second leading cause of acquired heart

disease after hypertensive heart disease.

13

Current data regarding

adherence rates to secondary benzathine penicillin prophylaxis

among these patients are unknown despite our knowledge

that good adherence is protective for severe forms of RHD.

Therefore, the study aims were (1) to determine the level of

adherence to benzathine penicillin prophylaxis among rheumatic

heart disease patients attending Mulago Hospital, (2) establish

the patient factors associated with adherence and, (3) establish

the reasons for missing monthly benzathine penicillin injections.

Methods

Institutional ethics approval was obtained from the School of

Medicine Research and the Ethics Committee of the College of

Health Sciences, Makerere University. We obtained informed

consent for all the patients and informed assent for those unable

to give consent. Patients’ initials and study numbers were put on

the questionnaires instead of full names to ensure confidentiality.

This was a longitudinal observational study carried out in

Mulago Hospital, the national referral hospital, and Makerere

University teaching hospital located in Kampala, Uganda,

which receives more than 250 patients with RHD annually. The

target population included all patients clinically diagnosed with

rheumatic heart disease and confirmed by echocardiography, as

previously described.

5

New and old RHD patients aged five to 55 years who were

eligible to continue prophylaxis for a period not less than one

year from the time of recruitment and consented to the study

were recruited. Each patient was then given a benzathine

penicillin prophylaxis card recommending the appropriate

monthly (four-weekly) dose of benzathine penicillin according

to the Uganda clinical guidelines, which recommends 2.4 MU

for adults, 0.6 MU for children

≤

30 kg and 1.2 MU for those

>

30 kg.

8

Patients with known allergy to benzathine penicillin were

excluded from the study.

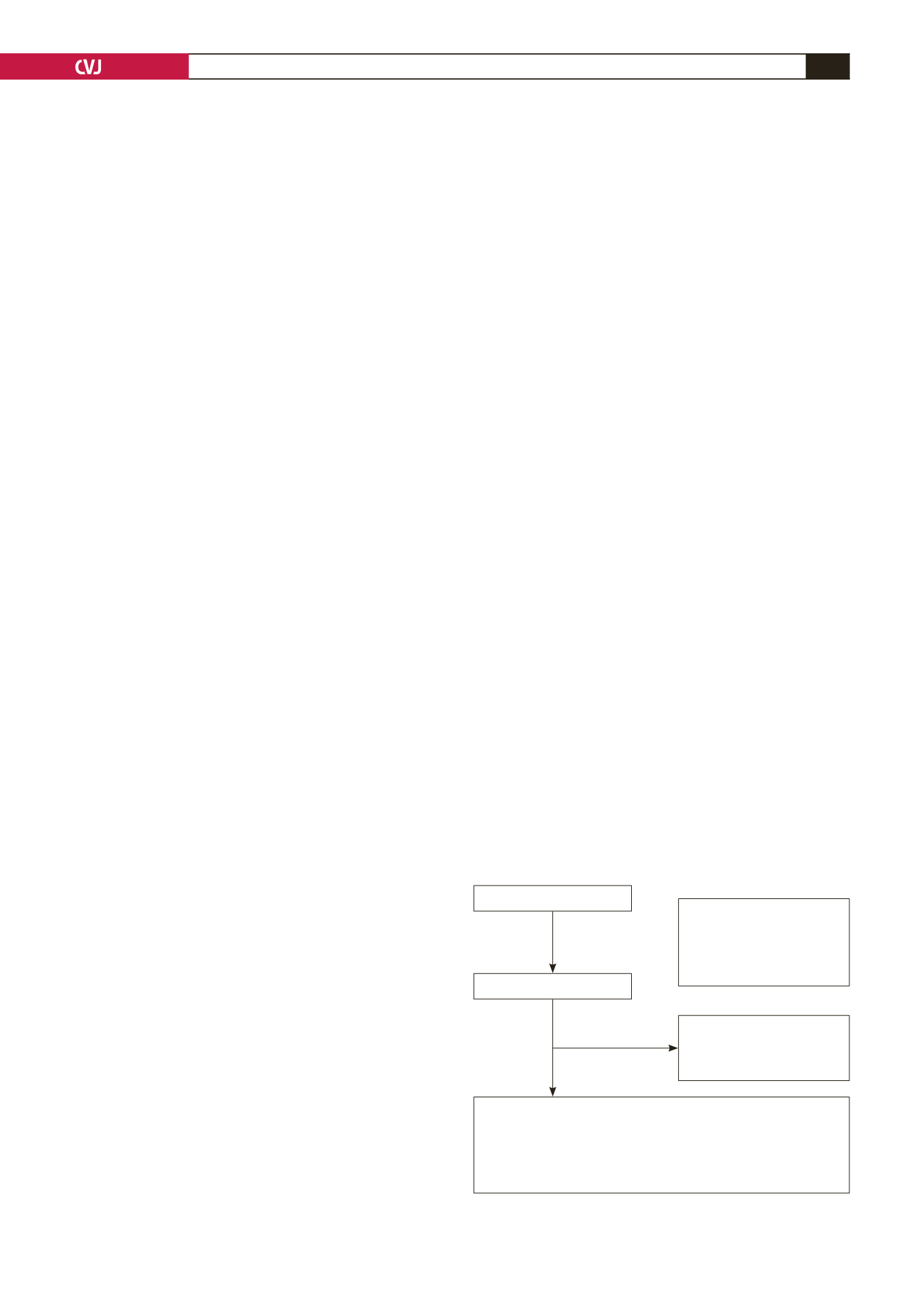

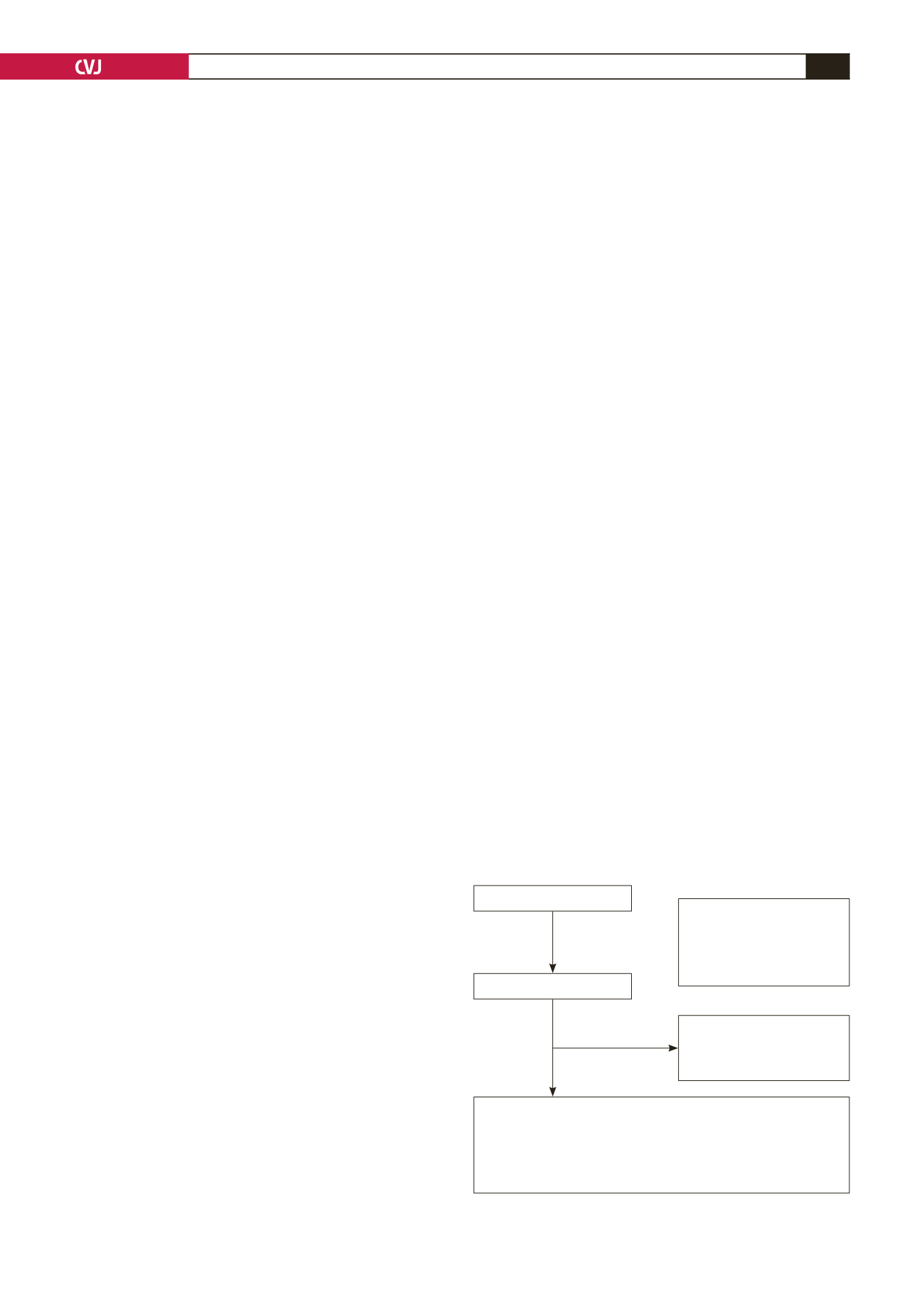

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively

recruited over a period of four months until a total of 95 patients

was reached (Fig. 1). An identification number or unique

patient number (UPN) was assigned to each consenting patient.

For those who refused to consent, the reason for refusal was

documented in the study book.

A focused clinical assessment was done using a standardised

pre-tested questionnaire in which the socio-demographic data,

details of physical findings, and details of findings on the

electrocardiogram and at echocardiography were recorded. In

addition, data regarding the following were collected: personal

history of hypertension, diabetes, stroke and other heart diseases.

Socio-economic factors recorded were educational level,

occupation, and total income (of parents in the case of children

or students).

For each patient recruited, information regarding the

importance of secondary prophylaxis was provided as part of the

whole information package given to the RHD registry patients,

including all their other treatment modalities. This was done in

liaison with the primary attending clinicians. This was to help

capture the dates and signatures of the health workers where

the patient received the benzathine penicillin injections over

the following six months. The card had the name of the patient,

which would help track the patients’ UPN through the study

book.

For purposes of limiting loss to follow up, data concerning

the following were collected: the patients’ phone numbers if

available/number of the caretaker for children; phone numbers

of at least two close relatives or friends, which would be tested at

the time of recording to ascertain their existence; the number for

the principle investigator was written at the back of each patient’s

benzathine penicillin card, and patients were urged to call and

inform the principle investigator if they were planning to change

their phone numbers.

After recruitment, each patient was told to continue attending

his/her regular clinic, as scheduled by the primary care clinician,

and he/she was to be reviewed in the general RHD registry every

three months by other registry clinicians. For this particular

study, the patients were reviewed again at the end of six months’

follow up.

At the six-month follow-up visit, patients were contacted

by phone and were encouraged to come with their benzathine

penicillin prophylaxis cards so that data regarding their rates of

adherence could be extracted. Those who were unable to travel at

the six-month follow for various reasons were requested to read

off the number of injections received at the time of the call from

the card, and this was recorded in their follow-up questionnaire.

These patients were nevertheless encouraged to take time off and

Fig. 1. Patient flow during the study.

Adherence to benzathine penicillin for secondary

prophylaxis among patients affected with rheumatic

heart disease (RHD) at Mulago Hospital

112 assessed for eligibility

17 ineligible

• 6 probable RHD

• 4 congenital heart disease

• 4 mitral valve prolapse

• 3 refused to consent

95 recruited

13 (13.7%) did not complete

6-month follow up

• 10 died

• 3 lost to follow up

82 (86.3%) completed 6-month follow up

Of these

• 71 (86.6%) had objective assessment of adherence (using the

benzathine card)

• 11 (13.4%) self-reported adherence (6 had lost card upon the

visit and 5 followed up over the phone.)