CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 4, July/August 2015

e10

AFRICA

Discussion

Cardiac involvement in lymphomas is a rare clinical presentation

with a dismal prognosis, occurring either as a primary cardiac

lymphoma,

1

or, more frequently, as secondary involvement

in the late evolution of aggressive lymphomas.

2

The clinical

presentation of cardiac involvement in lymphoma is variable.

Often, diagnosis is made by routine echocardiography. This is

regularly performed because evaluation of cardiac function is

important for assessment of the tolerability and side effects of

chemotherapy, especially in anthracycline-containing regimens,

which are known for their cardiotoxicity.

3,4

Even if the frequency of this type of tumour appears to be

increasing, real epidemiological figures are unknown, helped by

the fact that involvement of the heart is often asymptomatic.

Although rarely diagnosed during neoplastic clinical evolution,

cardiac metastases have been found in more than 10% of post

mortem examinations of patients succumbing to cancer,

5

more

frequently in melanoma, lung and breast cancer.

In lymphoma patients, post mortem figures for cardiac

involvement range from nine to 20%.

5,6

The diagnostic difficulty

in late evolution of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is associated with

the fact that heart failure may also be due to cumulative cardiac

toxicity of multiple lines of treatment and of the toxic cardiac

effects of anthracyclin-based chemotherapy regimens.

7,8

The

role of

18

F-FDG PET scans in detecting cardiac involvement

of lymphoma has been described in several case reports of

extralymphatic tumour involvement in lymphoma.

9,10

In our patient, cardiac involvement appeared as a late

evolution of an aggressive DLBCL. After four lines of chemo-

immunotherapy, including autologous stem cell transplantation,

the patient relapsed with mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Because

of the high cumulative dose of anthracyclines, well known for

their cardiotoxic effect, we chose to continue with a regimen

containing less cardiotoxic pegylated anthracycline, associated

with alkylating agent cyclophosphamide. After two cycles

the patient developed clinical signs of right cardiac failure.

Examination by PET scan found the presence of a massive

pericardial effusion (Fig. 1), but discordantly, complete remission

of the initial localisations of the lymphoma.

Our first hypothesis on the cause of the effusion was

the cumulative toxic effect of chemotherapy, but cytology,

immunophenotyping and cytogenetic analysis of the liquid

obtained by puncture showed the presence of lymphoma.

Lymphoproliferative disease is regarded as systemic and

pericardial, i.e. extralymphatic involvement is a sign of the

highest degree of dissemination in lymphoma staging, warranting

systemic therapy after removal of the pericardial effusion fluid,

rather than performing pericardiectomy or pericardial sclerosis.

Conclusion

We suggest that, if signs or symptoms of cardiac failure develop

during or after chemotherapy for lymphoma, the hypothesis of

cardiac involvement of lymphoma should be considered. The

diagnosis of this usually late complication requires cytological

confirmation.

This work was supported by grant 1494 /2014 from the University of

Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj (to M Zdrenghea) and the European Social

Fund, Human Resources Development Operational Programme 2007-2013,

project POSDRU/159/1.5/S/138776 (to C Bagacean and M Zdrenghea). The

sponsors had no involvement in the collection, analysis and interpretation of

data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript

for publication.

References

1.

Ceresoli GL, Ferreri AJ, Bucci E, Ripa C, Ponzoni M, Villa E. Primary

cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: diagnostic and thera-

peutic management.

Cancer

1997;

80

: 1497–1506.

2.

Mikdame M, Ennibi K, Bahrouch L, Benyass A, Dreyfus F, Toloune

F. [Cardiac localization of non Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a study on four

cases].

Rev Med Interne

2003;

24

: 459–463.

3.

Sarjeant JM, Butany J, Cusimano RJ. Cancer of the heart: epidemiology

and management of primary tumors and metastases.

Am J Cardiovasc

Drugs

2003;

3

: 407–421.

4.

Meng Q, Lai H, Lima J, Tong W, Qian Y, Lai S. Echocardiographic and

pathologic characteristics of primary cardiac tumors: a study of 149

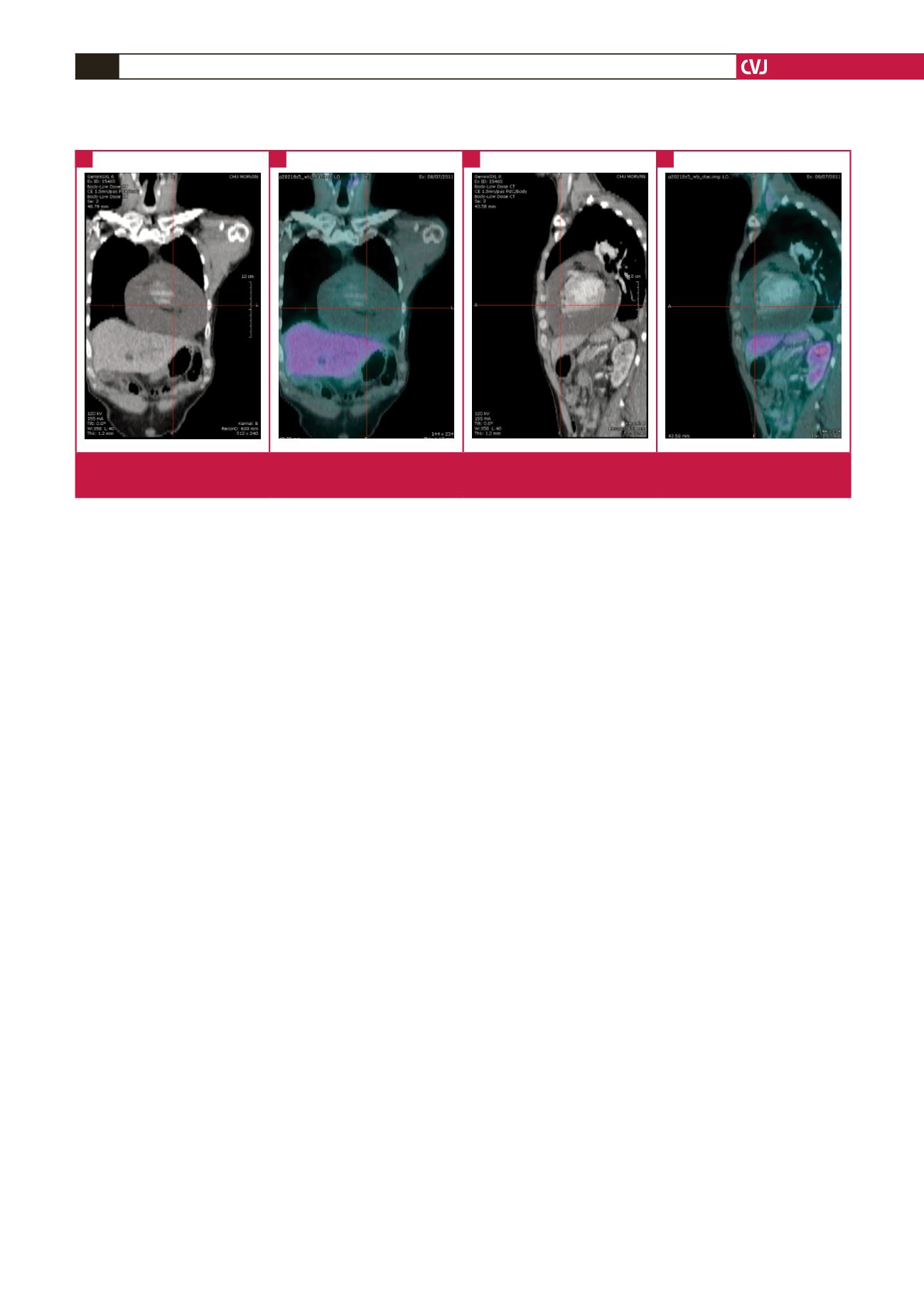

Fig. 1.

Coronal and sagittal CT and fused PET-CT reformatted images demonstrate large pericardial effusion (arrow). No abnormal

FDG uptake is noted.

A

C

B

D