CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 2, March/April 2017

AFRICA

135

(ECG) showed paced QRS with P wave at the end of the QRS

complex, indicative of atrioventricular dyssynchrony (Fig. 1).

These clinical findings, together with the ECG, raised the

suspicion of pacemaker syndrome.

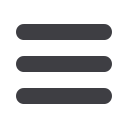

Pacemaker interrogation showed that his pacemaker was

programmed to AAIR–DDDR mode with a base rate of 70

bpm; the battery power was fine. The ECG showed typical right

ventricular pacing compatible with VVIR mode despite AAIR–

DDDR programming. Moreover, an atrial electrogram (EGM)

showed ventricular pacing and a ventricular EGM showed

sensed atrial depolarisation (Fig. 2). These findings were highly

suggestive of atrial/ventricular lead switch at the pacemaker

header. The underlying rhythm was sinus with an intrinsic rate

of 45 bpm. Chest X-ray and fluoroscopy showed that the atrial

and ventricular leads were situated in the correct positions in the

respective chambers.

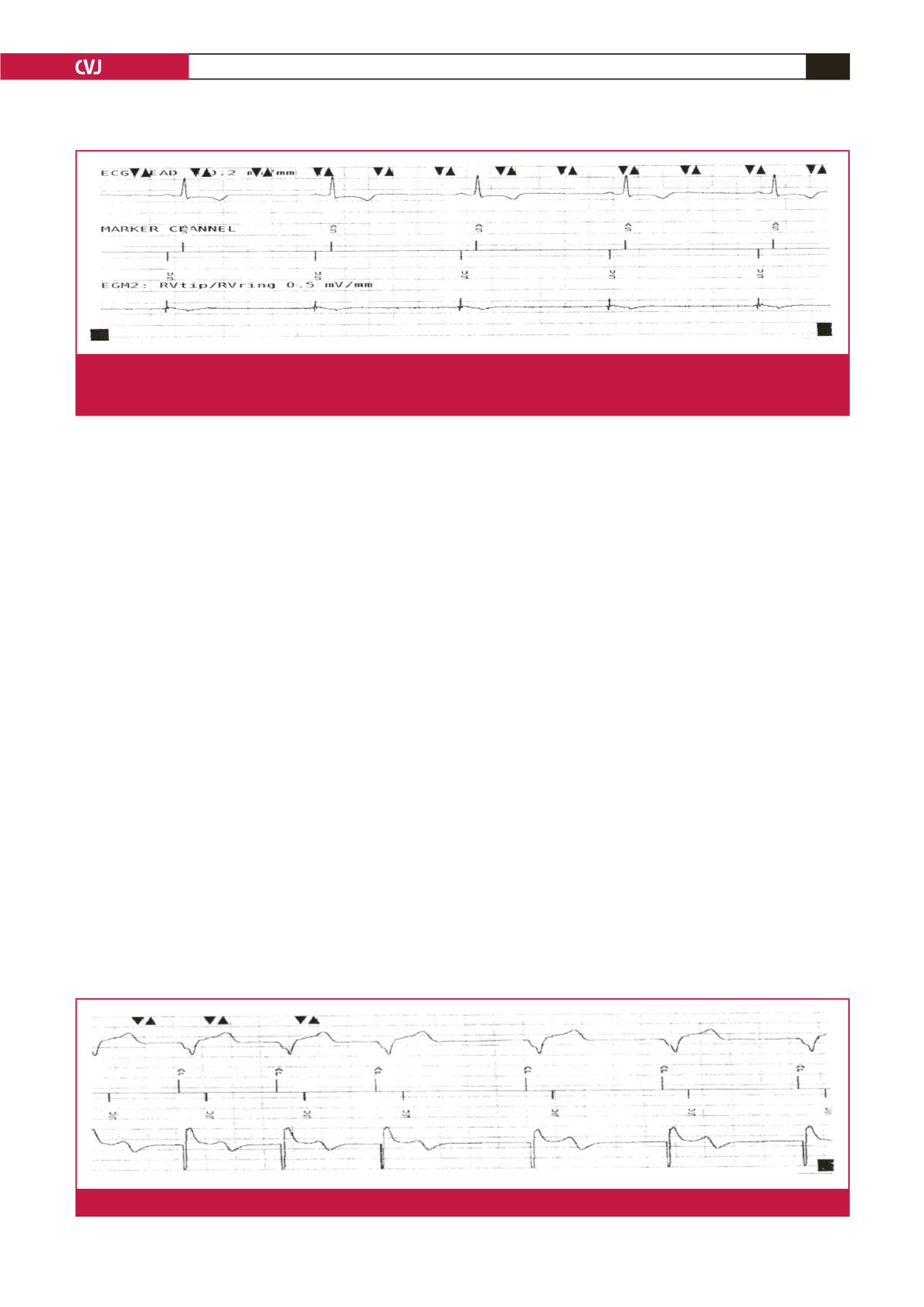

The patient subsequently underwent a corrective procedure

(lead repositioning) without temporary pacing cover. During

the procedure, it was confirmed that the leads were switched,

with the ventricular lead connected to the atrial port, and the

atrial lead connected to the ventricular port. Both the atrial and

ventricular leads were disconnected and tested, after which they

were reconnected to the appropriate ports at the pacemaker

header. Atrial pace and ventricular sense were achieved through

the AAIR–DDDR pacing mode (Fig. 3).

It was noteworthy that prior to correction, the blood pressure

was 108/62 mmHg, with a HR of 45 bpm. Post correction, the

blood pressure immediately rose to 141/77 mmHg, with a HR of

72 bpm (AP–VS).

An echocardiogram done later the same day showed that

the LVEF had dropped from 74 to 49% post pacemaker

insertion. This high LVEF was thought to have been due to

right ventricular-only pacing-induced left ventricular systolic

dysfunction.

The differential diagnosis for pacemaker syndrome includes:

acute coronary syndromes, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism,

pacemaker failure, pacemaker-mediated tachycardia and

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, among others.

5

In our case, the

rise in systolic blood pressure of > 20 mmHg post correction of

the leads confirmed the diagnosis of pacemaker syndrome.

The above differential diagnoses were ruled out as follows:

the cardiac biomarkers were negative with no ST changes on

the ECG, which ruled out an acute coronary syndrome. The

patient was biochemically euthyroid with no clinical features

of hyper- or hypothyroidism. The pacemaker was functional,

ruling out the possibility of pacemaker failure. The resting heart

rate was less than 100 bpm and this excluded the possibility

of pacemaker syndrome in this case being due to pacemaker-

medicated tachycardia. The patient was clinically not in left

ventricular failure, with clear lung fields on chest radiography

and on auscultation, and therefore cardiogenic pulmonary

oedema was an unlikely cause of his symptoms. Pulmonary

embolism was also ruled out based on a negative D-dimer

laboratory result.

Discussion

Pacemaker syndrome is defined as intolerance to ventricular-

based (VVIR) pacing due to loss of atrioventricular (AV)

synchrony.

6

It is an iatrogenic disorder that results from the

Fig. 2.

Electrogram showing typical right ventricular pacing, compatible with VVI mode despite AAIR–DDDR programming at the

pacemaker. This shows ventricular pacing when in fact pacing is from the right atrial lead. There is ‘atrial sensing’ from the

ventricular lead.

Fig. 3.

Twelve-lead ECG post lead repositioning showing proper atrial and ventricular pacing in AAIR–DDDR pacing mode.