CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 6, November/December 2017

400

AFRICA

The articles comprised five RCTs from Brazil and Iran and

two non-RCTs from Argentina and Iran, as shown in Table 3.

11,14-19

Characteristics of the interventions across the seven studies are

detailed in Table 4. Six of the trials studied the impact of exercise

alone on maternal and birth outcomes, and one study investigated

using fortified food to enhance micronutrient nutritional status.

A study by Prevedel

et al

.

17

was one of two that used aquatic

physical activity as an intervention. The relative body fat

percentage of the experimental group remained at 29%, however,

the control group increased by 1.9%.

A study by Cavalcante

et al

.

18

also used an intervention of

aquatic exercise during pregnancy to determine its effectiveness

onmaternal outcomes. No differences were noted between control

and intervention groups for weight gain during pregnancy, body

fat percentage, fat-free mass or body mass index (BMI).

The effects of supervised aerobic exercise on the maternal

outcomes of overweight pregnant women were evaluated by

Santos

et al

.

14

Although oxygen consumption of the exercise

group at anaerobic threshold was higher post intervention,

neither groups showed any differences in weight change after the

intervention.

Two Iranian interventions

16,19

evaluated the effect of land-

based exercise on low-back pain during pregnancy. The typical

exercise programme for these studies included a combination of

midwife-supervised anaerobic and aerobic exercise performed

three days per week at a moderate intensity. In the study by

Garshabi

et al

.,

19

lordosis was reduced in the exercise group after

the intervention, but weight gain was similar between the study

groups. In addition, spinal flexibility was significantly lower in

the exercise group post intervention, and this was correlated

with BMI. Weight gain was lower in the control group, and body

weight of the neonate was higher than in the exercise group.

Although Sedaghati

et al

.

16

showed intensity of low-back pain

was higher in the control group, weight gain during pregnancy

was higher in the exercise group.

The intervention that aimed to determine the possibility

of improving maternal outcomes using fortified foods

11

found

that the prevalence of folic acid and serum retinol deficiency

decreased, while vitamin A deficiency remained the same post

intervention. No differences were noted for body composition,

and the proportions of overweight and obesity in the groups

were at a moderate level of 20 and 26.3%, respectively, post

intervention.

Discussion

Pregnancy appears to be a pivotal time for both maternal and

foetal health. Emerging research has highlighted the profound

effects of the

in utero

environment on the lifelong health of the

baby. More specifically, both underweight and overweight babies

are at risk of obesity later on in life.

20

The perinatal period has

been cited by Lawlor and Chaturvedi

21

as one of the three critical

periods in life for the prevention of obesity.

Maternal obesity is perhaps one of the major causes of intra-

uterine over-nutrition during pregnancy, and can lead to large-

for-gestational-age deliveries. In addition, excessive gestational

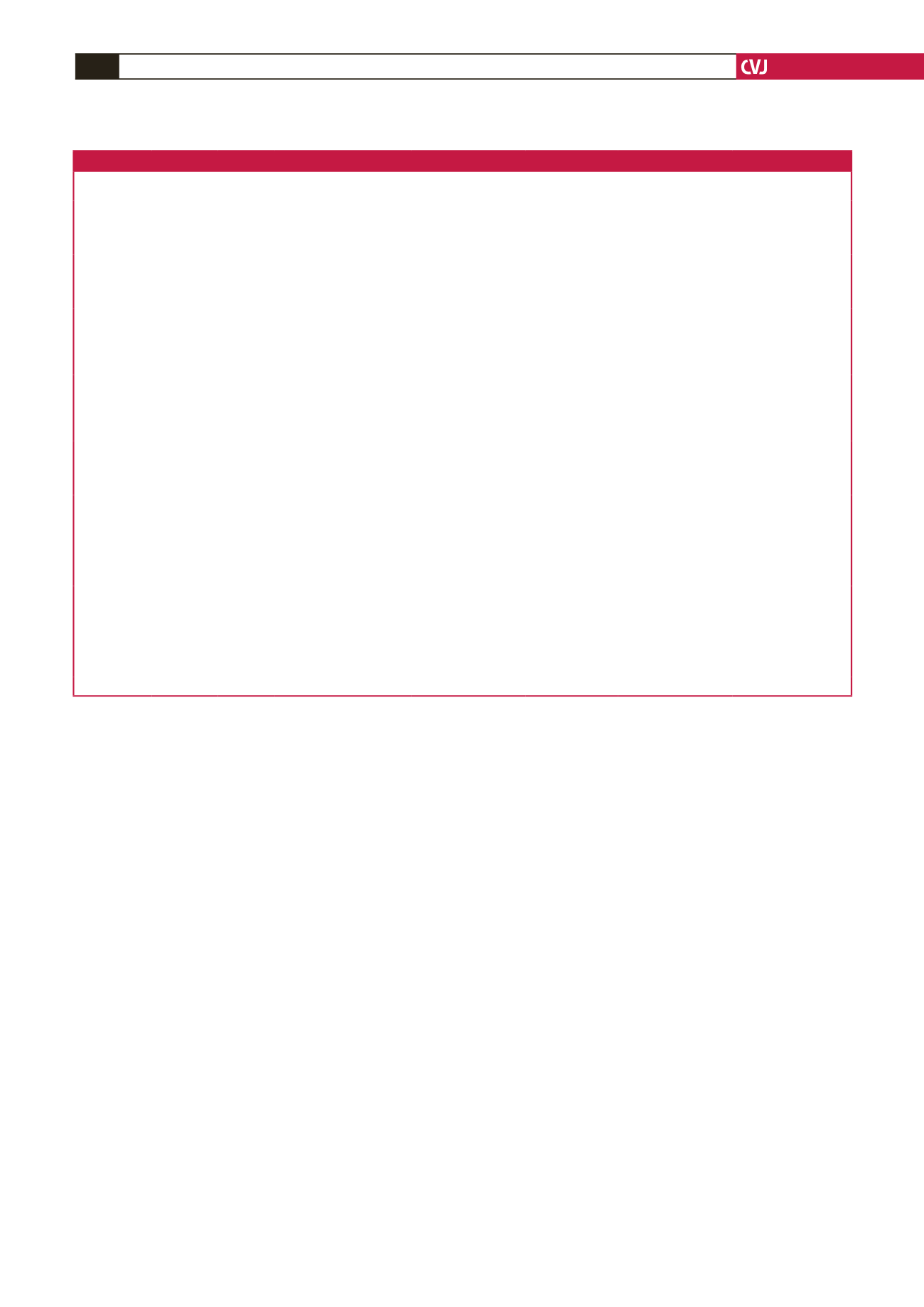

Table 3. Details and characteristics of the final studies included in the systematic review

Author

Type of

study

Country Region

Study setting

(urban/rural) Inclusion criteria

Sample size

Age (years)

Gestational age (weeks)

Santos

et al

.,

2005

14

RCT

Brazil

Porto

Alegre

Public health

clinic (not speci-

fied)

Healthy, non-smoking,

≥ 20 years, gestational

age < 20 weeks; BMI

26–31 kg/m

2

Control 35

Exercise 37

Control 28.6 ± 5.9

Exercise 26.0 ± 3.4

Control 18.4 ± 3.9

Exercise 17.5 ± 3.3

Garshasbi

et

al

., 2005

19

RCT

Iran

Tehran Hospital

Primi-gravid, 20–28

years old, 17–22 weeks’

gestation, housewives,

high-school graduated

Control 105

Exercise 107

Control 26.48 ± 4.43

Exercise 26.27 ± 4.87

Not specified

Malpeli

et al

.,

2013

11

Non-

randomised

Argentina Buenos

Aires

Urban

Sample from low-

income families, preg-

nant women, without

chronic or infectious

diseases

Control 164

Experimental 108

Control 25.8 ± 6.4

Intervention 26.3 ± 7.1

Control 23.6 ± 9.3

Intervention 24.3 ± 8.00

Sedaghati

et

al.

, 2007

16

Non-

randomised

Iran

Qom

province

Pre-natal clinics Exclusion: history of

orthopaedic diseases

or surgery, history of

exercise before preg-

nancy

Control 50

Experimental 40

Control 23.36 ± 4.237

Exercise 23.28 ± 2.522

Control 38.884 ± 1.232

Exercise 39.195 ± 0.921

Prevedel

et al.

,

2003

17

RCT

Brazil

Sao

Paulo

Pre-natal clinic

of the Faculty

of Medicine de

Botucatu (urban)

Primi-gravid or

adolescents, single-

ton pregnancies, no

co-morbidities

Intervention 22

Control 19

Mean: 20 years

16–20

Cavalcante

et

al

., 2009

18

RCT

Brazil

Sao

Paulo

Pre-natal out-

patient clinic of

the University of

Campinas and

the neighbouring

basic healthcare

centre

Low-risk, sedentary

pregnant women who

had not had more than

1 C-section and were

able to participate in

physical exercise

Intervention 34

Control 34

Not specified

16–20

Ghodsi &

Asltoghiri,

2012

15

RCT

Iran

Unspec-

ified

Pre-natal clinics

and hospitals

BMI 19.8–26 kg/m

2

;

lack of specific disease,

willingness to partici-

pate, correct address

for follow up; ability to

read and write; nulli-

and primi-gravid

Total sample 250;

unclear on

specific numbers

in each group

Control 25.86 ± 4.90

Training 25.43 ± 4.52

20–26

RCT = randomised, control trial; BMI = body mass index.