CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 28, No 6, November/December 2017

AFRICA

347

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human

Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and

Health Sciences of the University of Stellenbosch (U15/09/002).

We conducted a retrospective review of adult patients (18

years or older) admitted to Tygerberg hospital (TBH), Cape

Town, with warfarin toxicity during a one-year period from June

2014 to June 2015. Only patients known to be on established

warfarin therapy were eligible for inclusion. Patients who

were initiated on warfarin therapy during admission were

excluded. Patients admitted more than once during the study

period were recorded separately for each admission. We used

National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) records to identify

patients with raised INRs and reviewed clinical notes, laboratory

investigations and prescription data.

We collected demographic information, admission and

discharge dates, INR measurements, the presence or absence

of bleeding, sites and complications of bleeding, management,

presumed cause of warfarin toxicity as recorded in the clinical

notes, and whether it was addressed prior to discharge, as well

as concomitant medicine use at time of admission. The cause of

warfarin toxicity was recorded as not identified if a cause was

not recorded in the clinical records. In the presence of bleeding,

we classified it as major or non-major bleeding. Major bleeding

was regarded as life- or limb-threatening bleeding, whereas all

other cases where regarded as non-major bleeding.

We included patients presenting with warfarin toxicity, as

defined by an admission INR value greater than 5. Patients

included required at least one additional in-patient INR

measurement to capture only in-patients. We excluded patients

with an elevated INR who were not using warfarin and presented

with elevated INRs due to other pathology such as liver

impairment and sepsis. Patients with one elevated INR reading

but who died prior to an additional INR measurement being

done were not eligible for inclusion.

We calculated the warfarin toxicity treatment cost using the

procurement cost of blood and blood products from the Western

Cape Blood Transfusion Service, procurement cost of medicines

from the TBH pharmacy, and cost to the hospital to admit

a patient in a general ward in TBH using 2015 financial year

costing. The general ward admission cost included personnel

cost, clinical consumables, maintenance and engineering,

equipment, services and overhead costs.

We used DRUG-REAX

®

Interactive Drug Interactions

database (Truven Health Analytics Inc, Micromedex

®

Healthcare

Series)

8

to identify possible drug–drug interactions (DDI) between

warfarin and drugs used by patients at the time of admission.

Statistical analysis

No sample size was calculated and all patients identified during

the study period were included. Data were entered into Microsoft

Excel

®

and analysed using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College

Station, TX, USA). We assessed the normality of the data

visually and using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed

data are described using the mean and standard deviation

(SD) while non-normally distributed data are described using

median and interquartile ranges (IQR). We explored statistical

significance using appropriate tests for categorical, normal

numerical and non-normal numerical data.

Results

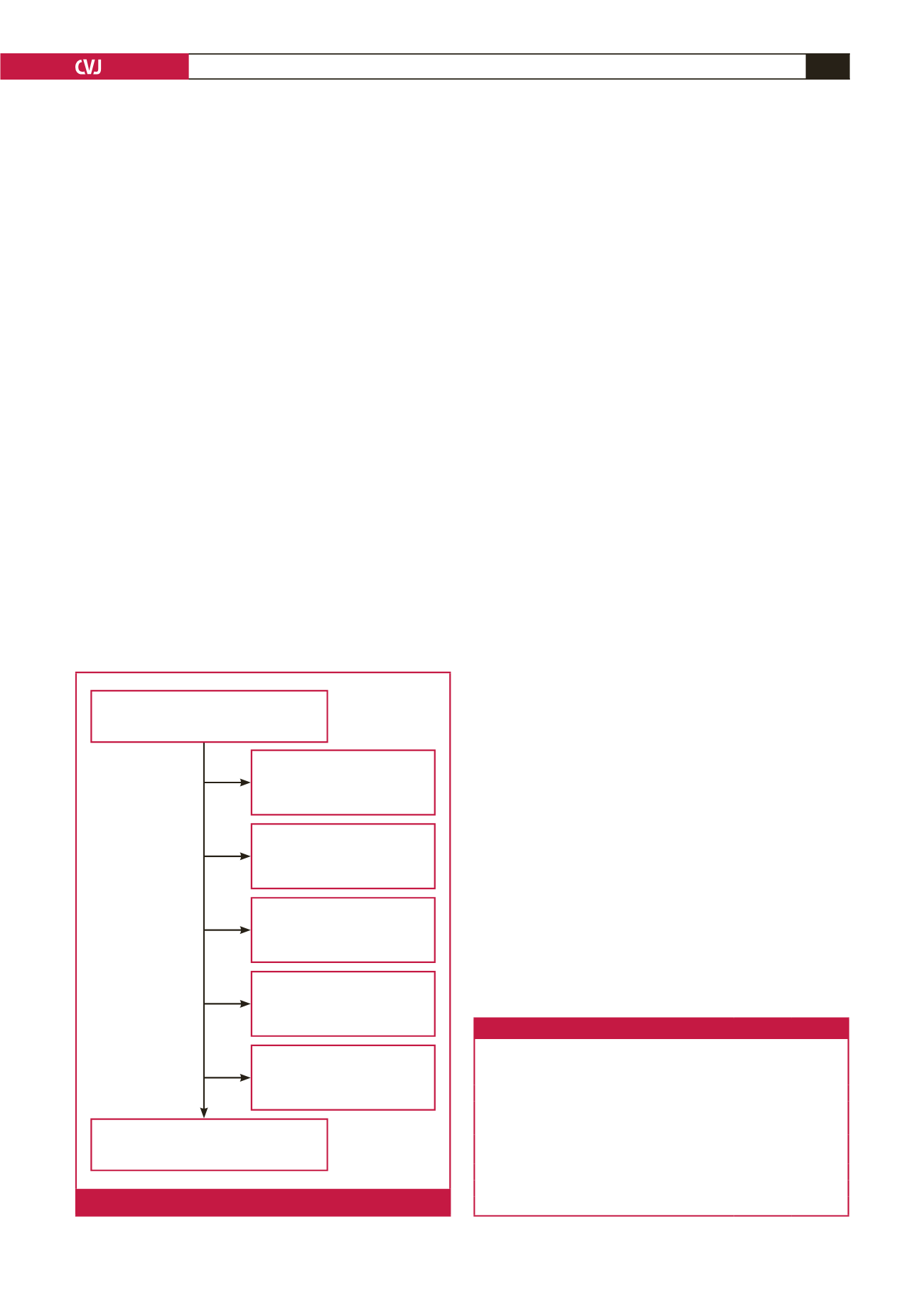

We identified 474 raised INR measurements (467 patients), of

which 126 (122 patients) met our inclusion criteria for warfarin-

toxicity admissions (Fig. 1). Four patients presented with two

admissions for warfarin toxicity during the study period and

each admission was recorded. For clarity we will refer to the 126

warfarin-toxicity admissions as patients.

Sixty per cent (76/126) of patients were female and 40%

(50/126) were male, with a median (IQR) age of 61 (48–70)

years. Fifteen per cent (19/126) of patients died before discharge,

although we could not attribute with certainty cause of death to

warfarin toxicity. Patients were admitted for a median (IQR) of

eight (5–16) days. The most common indications for the usage

Table 1. Indications for warfarin therapy

Indication

Number

of patients Percentage

AF

48

38

Heart valve replacements

24

19

DVT

21

17

Other

21

17

Multiple indications (including, but not limited to AF,

heart valve replacements and DVT)

9

7

Unknown

3

2

Total

126

AF

=

atrial fibrillation, DVT

=

deep-vein thrombosis.

Excluded due to no records

being available (

n

= 55)

Raised INR measurements identified

(

n

= 474)

Excluded due to not being

admitted (

n

= 24)

Excluded due to only one

INR measured (

n

= 46)

Excluded as not on warfarin

at admission (

n

= 187)

Excluded due to not being

admitted (

n

= 24)

Patients eligible for inclusion

(n = 126)

Fig. 1.

Study sample selection.