CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 5, September/October 2018

AFRICA

293

suspected unrelated foetal anomalies and a third case of a

complex foetal anomaly probably attributable to warfarin.

Only 20 pregnancies (69%) had a normal neonatal outcome.

The women in this cohort had lengthy hospitalisations, with 20

patients (69%) requiring more than 30 days in hospital and 15

(52%) requiring three or more admissions.

Themortality rate (6.9%) in our cohort compares unfavourably

with similar local cohorts

9,13,15

and with a large meta-analysis

showing a 2.9% rate,

2

but favourably with UKOSS, a recent

United Kingdom population-based study.

16

Both mortalities

occurred postpartum after discharge and in patients with double

valve replacements, which have been associated with worse

maternal outcomes.

16

Inducing an anticoagulated state opposes the pro-thrombotic

milieu of normal pregnancy.

17

Obstetric haemorrhage is known

to be a major contributor to maternal deaths.

18

Haemorrhage

rates were significantly high with 21% of patients having major

haemorrhagic complications. This rate is comparable with other

cohorts of women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves.

5,16

Another study

15

reported post-partum haemorrhage in only 5.8%

of patients. These variable rates may reflect differing practice in

the timing of anticoagulation reintroduction.

The anticoagulation protocol used prescribes heparin rather

than warfarin from 36 weeks’ gestation, allowing rapid reversal

of anticoagulation if required during delivery. Delivery takes

place during an anticoagulation-free ‘window’ to minimise risk of

post-partum haemorrhage. There is a need to identify the optimal

duration of this ‘window’ to balance the risks of haemorrhage

and thrombosis. Heparin is usually reinstated six hours after

delivery unless there is clinical concern of haemorrhage.

Of the 19 pregnancies delivered after viability, and

consistent with other literature,

19-21

post-operative haemorrhage

(3/9 caesarean sections, 33%) was more frequent than major

haemorrhage post-vaginal delivery (1/10 normal vaginal

deliveries, 10%), indicating that a longer anticoagulation window

may be appropriate after operative delivery. The data suggest

that caesarean sections should be performed only when clearly

indicated, with meticulous haemostasis, and in anticipation of

possible haemorrhage.

Despite the risk of major bleeding, neither death occurred as

a direct result of bleeding. However, cases of major haemorrhage

would have resulted in deaths had resuscitation, including

transfusion not been available.

Only one patient had a suspected thrombo-embolic event.

Two further patients had ischaemic strokes in the setting of HIV

positivity.

Protocols used called for intravenous unfractionated heparin

from six to 12 weeks’ gestation and peripartum, according

to relevant guidelines.

14

However, more recent guidelines

22

recommend subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin

(LMWH) (enoxaparin, Clexane) in preference to unfractionated

heparin (UFH), dose adjusted according to peak anti-Xa levels.

LMWH has more predictable pharmacokinetics and less risk

of allergic reactions, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and

osteoporosis compared to UFH.

22,23

However, there is concern

that the use of subcutaneous UFHmay lead to unacceptably high

rates of treatment failure and valve thrombosis.

24

Consequently,

intravenous UFH is generally recommended and may remain the

only alternative to warfarin where access to anti-Xa monitoring

is limited, such as in our setting.

Intravenous heparin infusions are, however, resource intensive,

requiring frequent monitoring and prolonged hospitalisation.

The single suspected thrombotic event occurred in a patient

receiving UFH while in a sub-therapeutic range. However, even

ideal anticoagulation can lead to treatment failure.

In general, heparin use avoids the pregnancy loss and

embryopathy associated with warfarin but carries a higher risk

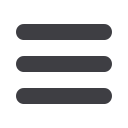

Table 5. Maternal and foetal outcomes

Outcomes

Number (%)

Maternal outcomes

NYHA FC (

n

=

13)

I/II

12

III

1

Deaths

2

Delivery

Vaginal

19 (66)

Caesarean

9 (31)

Hysterotomy

1 (3)

Reasons for surgical delivery

Foetal distress

3

Previous caesarian section

2

SROM

2

Other

3

Bleeding complications

Major bleeding

7 (24)

Blood transfusion

8 (28)

Thrombotic complications

4 (14)

Arrhythmias

11 (38)

Time in hospital

Hospital stay (days)

41

±

28

Admissions

3

±

1.8

Foetal outcomes

Healthy

19 (66)

Birth weight (g) (

n

=

19)

<

2 kg: 2

2–2.5 kg: 4

2.5–4 kg: 13

Apgar score at 5 min (

n

=

18)

Apgars 9–10: 17

Apgars 7: 1

Born before arrival: 1

ENND

1 (3)

Pregnancy loss

6 (21)

Termination

3 (10)

NYHA FC: New York Heart Association functional class, SROM: spontaneous

rupture of membranes, ENND: early neonatal death.

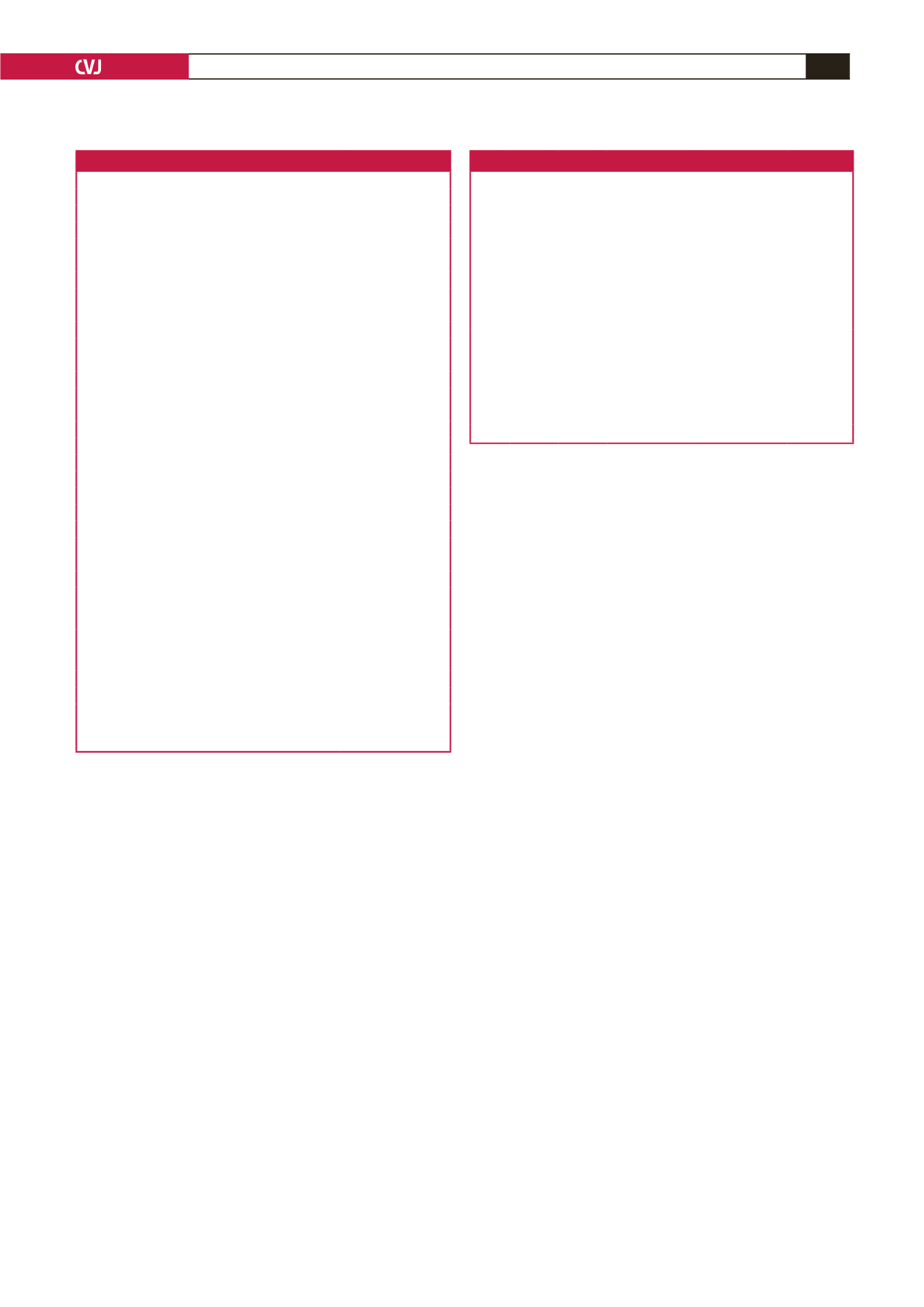

Table 6. Congenital abnormalities including warfarin embryopathy

Patient

no

Maternal

age

GA at 1st

antenatal

visit

Parity

Antico-

agulant

and dose Sonography

Foetal

outcomes

1

25

24

1

Warfarin,

5 mg

Polyhydramnios,

abnormal facies,

close-set eyes,

absent nose, low-

set ears, bossed

forehead, abnormal

ventricles, short

spine, fat puffy

hands and feet

ENND

2

29

17’5

2

Warfarin

5 mg in

T1 then

defaulted

Dandy–Walker

malformation

Termination

at 19 weeks

3

38

19’1

4

Warfarin

7.5 mg

daily

Echogenic bowel

Termination

at 22 weeks

GA: gestational age, ENND: early neonatal death, T1: first trimester.