CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 5, September/October 2020

AFRICA

239

involvement of the heart in HIV-infected patients.

9

However, it

appears that HAART converted symptomatic cardiac disease

to mild or asymptomatic disease in one study,

14

significantly

improving patient survival and quality of life. Our study was not

powered to draw any conclusions as to the effect of HAART

on incidence of cardiac involvement, since we did not compare

patients on ART with those who were not.

We also performed TDI studies on both the LV and RV

(Table 2). TDI has been shown to unmask subtle abnormalities

that were not detected by conventional echocardiography.

32,33

Some important abnormalities were observed in our patients. A

significant proportion of patients who had normal findings on

conventional echocardiography had shown abnormal MPI, LV

diastolic dysfunction and RV systolic and diastolic dysfunction

on TDI. MPI, which involves load, heart rate and ventricular

geometry, and is an independent measure of systolic and

diastolic ventricular function, was also abnormal for both

ventricles in our group of patients compared to critical cut-off

points and

Z

-scores set by multiple investigators in the past,

23,34-37

indicating the presence of subclinical LV and RV dysfunction.

MPI includes both diastolic and systolic time intervals and is a

sensitive marker of ventricular systolic and diastolic function,

even when it is unrecognisable by conventional echocardiography.

Our study attempted to show an association between

patient clinical factors such as age, gender, BMI, World Health

Organisation clinical stage, previous treatment for opportunistic

infections, CD4 count, age at initiation of HAART, duration

of HAART and having a specific type of cardiac involvement

such as increased LV mass index, LV diastolic dysfunction, or

RV systolic/diastolic dysfunction. We did not find a statistically

significant association. We then considered an association

between such patient factors and having any of the cardiac

abnormalities combined (Table 3). Although there was a

tendency towards an association, none of these reached a

statistically significant level. Previous work by different authors

has also reported inconsistent associations between such factors

and cardiac involvement in children living with HIV.

4,13,16,38

Our study has important limitations. First, interpretation

of TDI findings was based on previously set reference values

and

Z

-scores. However, this has its own drawbacks and the

more appropriate way would have been to take a control

group of healthy children and adolescents matched for age

and gender. Second, there were other important and relevant

echocardiographic indices that we did not measure due to

logistical issues.

Conclusion

Our sample of children and adolescents living with HIV

had subclinical cardiac abnormalities detected on conventional

echocardiography as well as TDI. While few patients had

abnormalities detectable on conventional echocardiography,

such as reduced LV ejection fraction, pulmonary hypertension

and pericarditis, a larger proportion of patients had subtle

abnormalities, such as increased MMI, LV diastolic dysfunction,

RV dysfunction and abnormal MPI. However, to make better

sense of the TDI indices, it would probably have been better

to compare with a group of healthy children, drawn from a

similar socio-demographic background. Our study did not

show a strong association between specific patient factors and

echocardiographic abnormalities in this sample of patients.

We thank the staff of the Paediatric Infectious Disease Clinic for facilitating

the data-collection process. We are grateful to all patients who consented to

participate in this study. Our thanks go to Dr Dejuma Yadeta, who reviewed

our manuscript and gave us constructive comments. Last but not least, we

thank the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health for approving and

allowing the study to be conducted.

References

1.

UNAIDS: Global HIV and AIDS statistics fact sheet. World AIDS

DAY December 1 2018.

http://www.unaids.org. Accessed December

2018.

2.

Agwu AL, Fairlie L. Antiretroviral treatment, management challenges

and outcomes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents.

J Int AIDS Soc

2013;

16

: 1–13.

3.

Chelo D, Wawo E, Siaha V,

et al

. Cardiac anomalies in a group of

HIV-infected children in a pediatric hospital: an echocardiographic

study in Yaounde, Cameroon.

Cardiovasc Diagn Ther

2015;

5

: 444–453.

4.

Miller RF, Kaski JP, Hakim J,

et al.

Cardiac disease in adolescents with

delayed diagnosis of vertically acquired hiv infection.

Clin Infect Dis

2013;

56

: 576–582.

5.

Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, Orav EJ,

et al.

Left ventricular structure

and function in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus:

The Prospective P2C2 HIV Multicenter Study.

Circulation

1998;

97

:

1246–1256.

6.

Starc TJ, Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, et al. Incidence of cardiac abnor-

malities in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection: the

prospective P2C2 HIV study.

J Pediatr

2002;

141

: 327–334.

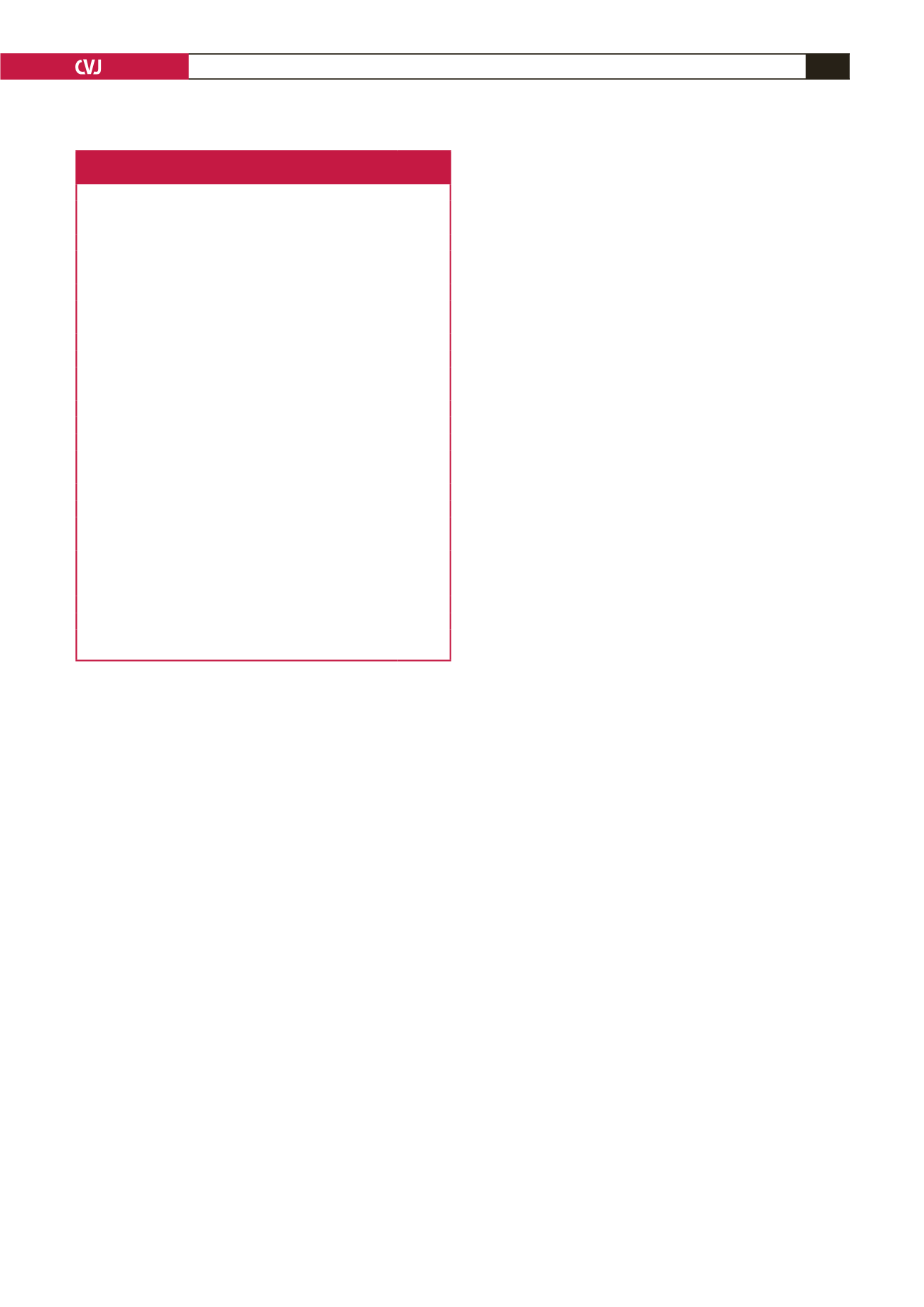

Table 3. Factors associated with cardiac abnormalities in

151 HIV-infected children and adolescents on HAART

Variables tested for association

Abnormal echo findings

p

-value

Age at time of study (years)

≤ 12

22/57

0.728

> 12

33/94

Gender

Female

28/83

0.498

Male

27/68

Body mass index

Z

-scores

<

–2

11/26

0.511

≥ –2

44/124

Initial WHO clinical stage

I and II

15/55

0.082

III and IV

40/96

Lowest CD4 count

<

200

39/97

0.220

≥ 200

16/54

Age at initiation of HAART (years)

<

9

11/80

0.490

10–13

14/59

14–19

2/12

Duration of HAART (months)

<

24

11/29

0.894

≥ 24

45/121

Previous treatment for opportunistic

infections (per WHO definition)

Yes

33/78

0.131

No

22/73

WHO, World Health Organisation; HAART, highly active antiretroviral treat-

ment; LV, left ventricular.