CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 22, No 1, January/February 2011

AFRICA

33

7). It is well known that over 90% of women in South Africa do

have antenatal care but infrequent attendance and delay in seek-

ing help remain major issues.

Case 1

Management of severe hypertension in the

antenatal period

The patient, a 27-year-old parity 3, had high blood pressure

during her antenatal visits. She had had a previous caesarian

(C/S) and had three antenatal visits at a tertiary-care centre.

At her last visit, her blood pressure was 170/110 mmHg, she

was admitted at 11:00 and methyl dopa was prescribed. She had

a seizure at 23:00 on the day of admission. Magnesium sulphate

(MgS0

4

) was prescribed and a C/S was performed ‘under platelet

cover’. Post-operatively, there was difficulty in controlling her

high blood pressure; she had HELLP with jaundice and demised

at 12:00 the next day.

Lessons to learn: immediate management of severe

hypertension

Careful history taking and obtaining results of investigations is

essential. It is not clear whether information on her past obstetric

history was obtained. If she did have a previous C/S for hyper-

tension, laboratory results should have been obtained soon after

admission and appropriate action taken timeously. In this case

the results were only obtained following her seizure.

It is uncommon, for patients to ‘fit’ under medical manage-

ment in a tertiary hospital but this case illustrates the fulminant

course of pre-eclampsia that some patients develop. Therefore

all patients who are admitted with severe hypertension should be

treated with urgency.

•

Obtain a good past history.

•

Lower very high blood pressure reasonably quickly, but in

a controlled manner. Dihydralazine, if available, should be

used. Alternate antihypertensive agents include labetalol and

nifedipine.

•

All blood investigations must be reviewed within two to four

hours of being sent to a laboratory. This patient had low plate-

lets and HELLP probably on admission and it is likely that her

high blood pressure was not controlled.

•

Intensive monitoring of blood pressure levels must be

performed until they are stabilised.

Cases 2–4: postpartum convulsions

A 37-year-old delivered a premature baby at a MOU and was

transferred to a tertiary hospital because the baby required

level 3 care. The patient, on admission to the tertiary hospital,

complained of symptoms in keeping with imminent eclampsia

and had hypertension. The intern failed to make the correct diag-

nosis; therefore no observations were carried out. The next day

the patient was found in a post-ictal state and subsequently had a

cardio-pulmonary arrest.

A 23-year-old, parity 3 had a C/S for foetal distress and immi-

nent eclampsia. On the second post-operative day she developed

‘mild pulmonary oedema’. She responded to initial treatment;

12 hours later, she convulsed and had a cardio-pulmonary arrest.

A parity 1 G 2 had severe pre-eclampsia. She had a normal

vaginal delivery but was discharged on day 1 following delivery,

with no treatment. She ‘fitted’ at home 24 hours later and had a

cardio-pulmonary arrest.

Lessons to learn

These cases illustrate features of severe pre-eclampsia syndrome

that are often not taken into account by inexperienced health

personnel. While it is true that in our current understanding of

the aetiology of pre-eclampsia that delivery of the foetus and

placenta leads to cure, it must be understood that these women

are still at risk of complications from the disease process in

the immediate post-delivery period. Therefore it is essential to

ensure continued frequent observations of the pulse rate, blood

pressure, urine output, level of consciousness and potential signs

of pulmonary oedema.

Antihypertensive therapy must be continued and should not

be stopped abruptly. Magnesium sulphate should be continued

for at least 24 hours following delivery. All laboratory tests

must be repeated within four to six hours following delivery

and results reviewed. Patients should not be discharged until

their high blood pressure levels are stabilised for a period of at

least 24 hours. Furthermore, these patients should be asked to

return to the postnatal clinic within a week and only referred to

a clinic when all physical and laboratory tests have returned to

normal. Generally speaking, these tests should have returned to

normal within seven days of delivery. Advice on contraception,

further pregnancies and place of future antenatal care should be

provided.

All three cases illustrate the above lessons, namely

•

failure to recognise symptoms and signs of imminent eclamp-

sia following delivery and consequently failure of post-deliv-

ery observations

•

failure to recognise dangers of pulmonary oedema, the need

for investigations and frequent observations

•

discharging patients from hospital prior to stabilising (lower-

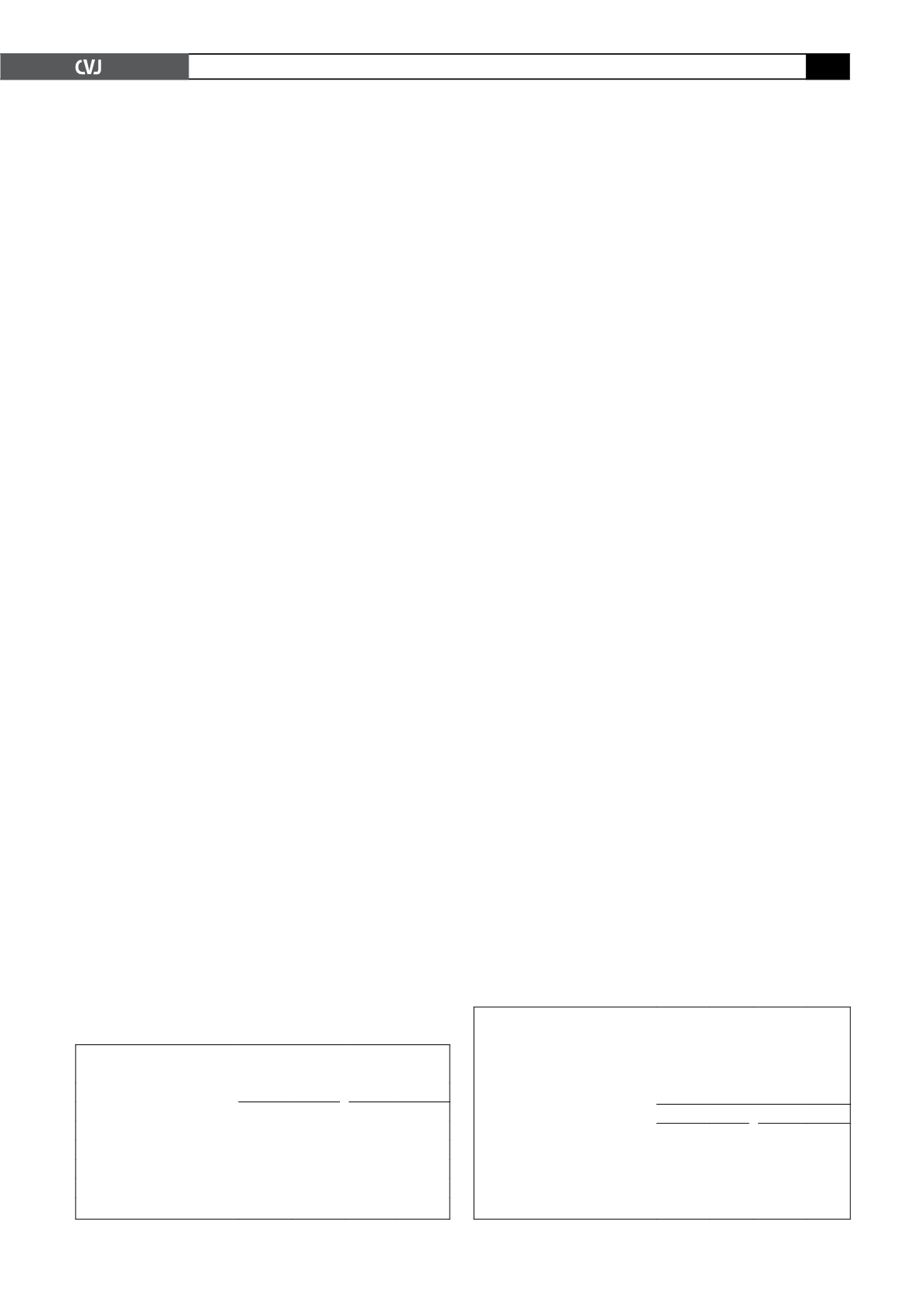

TABLE 6. TIMING OF EMERGENCY EVENT

RELATED TO HYPERTENSION

Category

2005–2007

2002–2004

n

% n

%

Early pregnancy

14

2.3

13

2.1

Antenatal period

335 53.9 206 48.7

Intrapartum

69 11.1

83 13.2

Postpartum period

209 33.6 228 36.3

Unknown

3

0.5

5

0.8

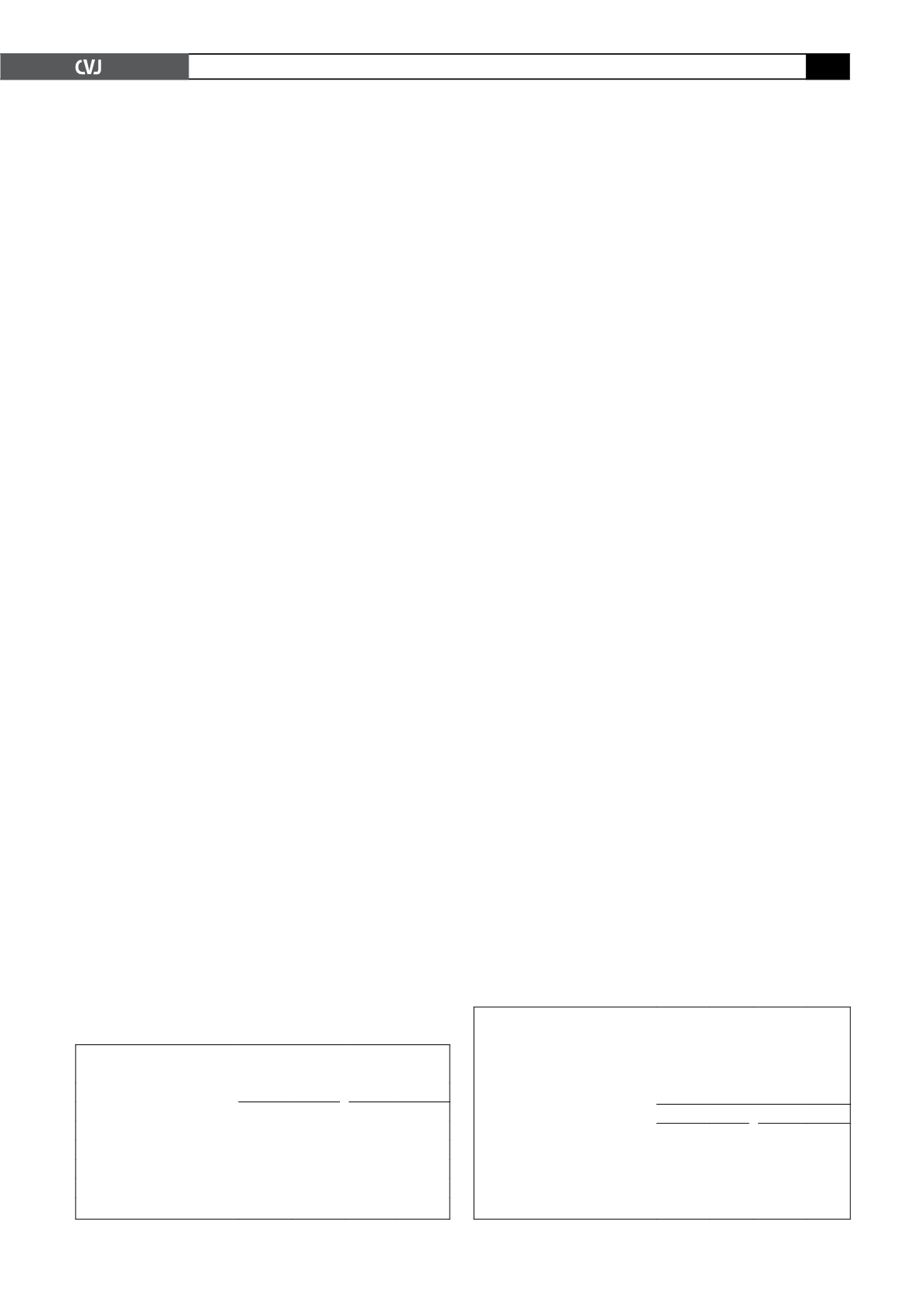

TABLE 7. AVOIDABLE FACTORS, MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

AND SUB-STANDARD CAREWITH RESPECT TO PATIENT-

ORIENTATED PROBLEMS FOR HYPERTENSIONANDA

COMPARISONWITH 2002–2004

Major problems

% of assessable cases with

avoidable factors

2005–2007

2002–2004

n

=

547 % n

=

524 %

Non-attendance of antenatal care 106 19.4 123 23.5

Infrequent attendance

40

7.3

36

6.9

Delay in seeking help

106 19.4 140 26.7

Other

45

8.2

38

7.3