CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 3, May/June 2015

AFRICA

117

compared to healthy controls, but there was no significant

difference between the MP users and cigarette smokers. Also,

the amount of MP used and cigarette smoking (pack years) was

correlated with LAAEV and LAAEF. This is the first study to

determine the atrial electromechanical and mechanical functions

of MP users and cigarette smokers.

Cigarettes have widespread use and their smoke contains

more than 4 000 toxic compounds, mainly nicotine. Various

clinical and pathological investigations have shown that cigarette

smoking caused atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and heart

failure,

4

and nicotine abuse is associated with the occurrence of

cardiac arrhythmias.

9,12

The pro-arrhythmic effect of cigarette

smoking seems to depend on the nicotine concentration in the

blood.

9

Increased nicotine levels increase atrial and ventricular

vulnerability to fibrillation.

9,12

These effects are more likely

to depend on the inhibition of ion channels and conduction-

slowing properties.

One factor known to cause a substantial slowing of electrical

impulse propagation in cardiac tissue is an increase in the

amount of interstitial collagen. It has been found that the

prolonged administration of nicotine is also associated with the

loss of intracellular K

+

and the emergence of cardiac necrosis.

21

Experimentally, Goette

et al

. established a linear correlation

between nicotine dose and atrial collagen expression, leading

to symptomatic atrial fibrosis at a younger age.

22

In previous

reports, atrial conduction time was found to be prolonged

independently of LA dilatation.

20,23

In a study consisting of

50 smokers and 40 non-smokers, it was found that inter- and

intra-atrial electromechanical delay was significantly higher

in cigarette smokers compared with non-smokers, and the

amount of smoking was strongly correlated with inter-atrial

electromechanical delay.

24

Distinct from that study, our study contained a third group, the

MP users, and we also investigated left atrial mechanical function

in our study population. Likewise, we found that although LA

was not dilated, atrial conduction time was prolonged in both

MP users and smokers. This may be explained as the negative

effects of nicotine on cardiac structure and function. The

development of interstitial fibrosis affects chamber geometry

and mechanical performance of the heart and enhances the

likelihood of cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation

(AF). Moreover, in prospective, population-based and 16-year

follow-up studies, it has been shown that smoking was associated

with incidence of AF, with more than a two-fold increased risk

of AF attributed to current smoking.

25

The risk of AF increased

with increasing cigarette years of smoking, and appeared to be

somewhat greater among current smokers than former smokers

with similar cigarette years of smoking.

25

MP is a form of smokeless tobacco. The ash in this mixture

transforms the alkaloids into a base form and provides easy

absorption from the buccal mucosa.

26

As MP contains six- to10-

fold more nicotine than cigarettes, it is preferred by addicts. It

has been shown that urinary cotinine levels were three times

higher in MP users than in cigarette smokers.

27

Besides, MP is

closely associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors

and endothelial dysfunction, as detected by low plasma NO

levels.

3

MP increases oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation

levels, which are the best indicators of cytological damage.

28

Because of the deleterious effects of cigarette smoking,

especially the nicotine blood level, it stimulates the sympathetic

nerve endings and increases adrenaline release, which in turn

increases cardiovascular abnormalities.

29

The probability

of abnormalities of the cardiac conduction system and the

Table 3. Findings of atrial electromechanical coupling

measured by tissue Doppler imaging

Group I

controls

(

n

=

50)

Group II

smokers

(

n

=

50)

Group III

MP users

(

n

=

50)

p

-value

Lateral PA (ms)

48.3

±

9.8 53.9

±

12.9 54.1

±

14.1

§

0.032

Septal PA (ms)

40.1

±

8.7 46.3

±

13.3

#

45.8

±

15.2 0.028

RV PA (ms)

34.1

±

8.4 38.4

±

9.9 37.5

±

12.7 0.098

Lateral PA–septal PA (ms)

8.1

±

3.5

7.9

±

4.3

8.2

±

3.9 0.687

Lateral PA–RV PA (ms)* 14.2

±

8.9 15.5

±

10.1 16.5

±

8.4 0.443

Septal PA–RV PA (ms)** 6.0

±

5.9

7.9

±

8.8

8.2

±

7.7 0.287

PA: the interval with tissue Doppler imaging, from the onset of P wave on the

surface electrocardiogram to the beginning of the late diastolic wave (Am wave).

*Inter-atrial dyssynchrony, **intra-atrial dyssynchrony.

§

p

=

0.05 versus group I,

#

p

=

0.04 versus group I.

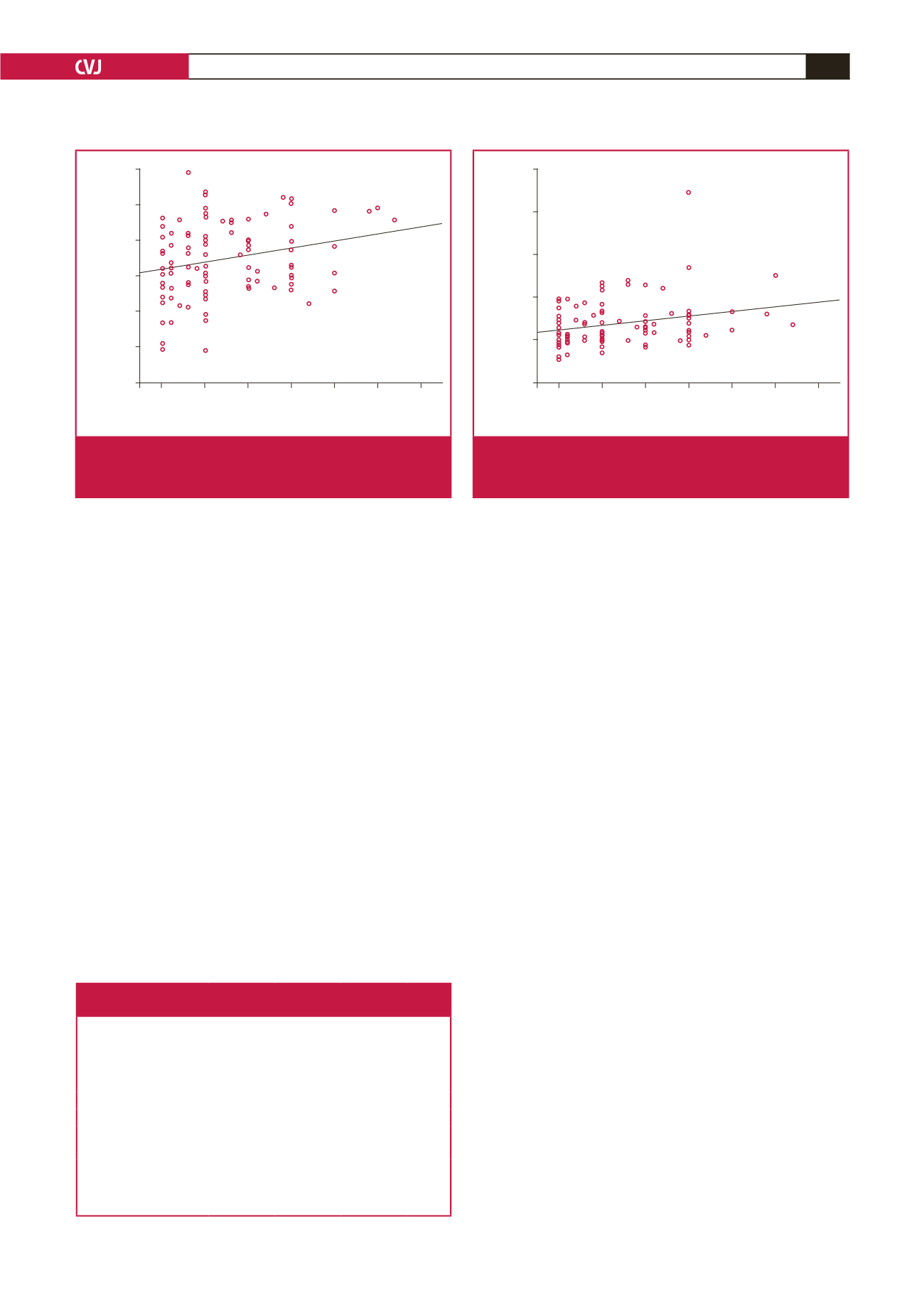

0.70

0.60

0.50

0.40

0.30

0.20

0.10

5.00 10.00 15.00 20.00 25.00 30.00 35.00

Duration (pack years)

Left atrial active emptying fraction (%)

R

2

linear

=

0.061

Fig. 1.

This shows positive correlations between LA active

emptying fraction and the amount of MP use and cigarette

smoking (pack years) (

r

=

0.25,

p

=

0.013).

25

20

15

10

5

0

5.00 10.00 15.00 20.00 25.00 30.00 35.00

Duration (pack years)

Left atrial active emptying volume (cm

3

/m

2

)

R

2

linear

=

0.069

Fig. 2.

This shows positive correlations between LA active

emptying volume and the amount of MP use and cigarette

smoking (pack years) (

r

=

0.26,

p

=

0.009).