CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

AFRICA

239

invention needed a third revascularisation to be carried out. A

total of 16 patients (eight males and eight females) needed more

than three surgical interventions.

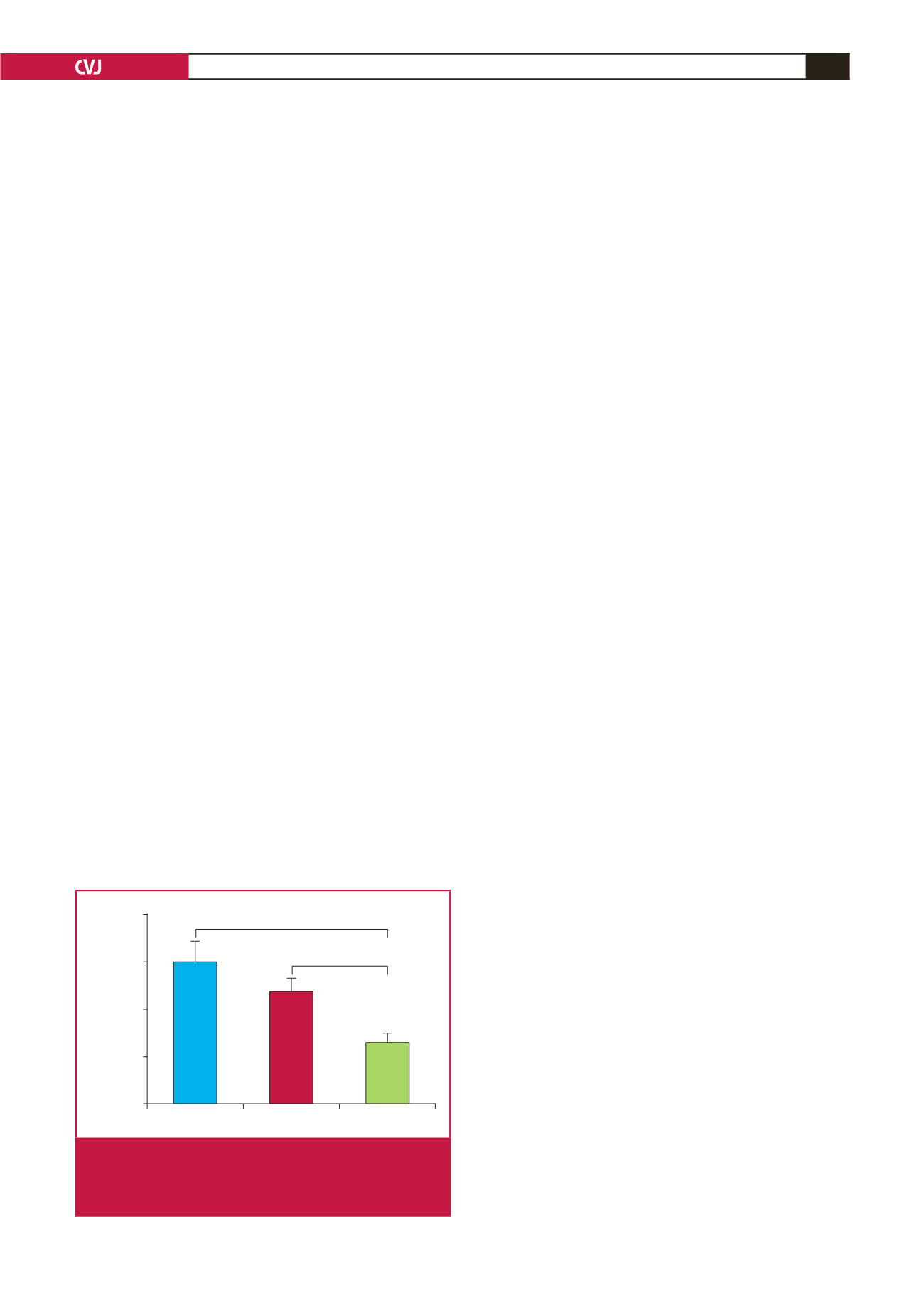

As depicted in Fig. 1, it took 60 months (five years) for

patients who were treated with OMT before their first surgical

intervention to require the second revascularisation. Those who

received SOMT and those who did not receive medication at all

before their first surgery took 48 and 26 months, respectively,

to require the second revascularisation. The differences (i.e.

34 months) between those who were on OMT and those who

did not receive any medical therapy before their first surgical

intervention were statistically significant (

p

<

0.001).

Similarly, the differences (22 months) between those who

were on SOMT and those who did not receive any medical

therapy before their first surgical intervention were statistically

significant (

p

<

0.05). The specific type of the first surgical

intervention had a significant (

p

<

0.05) impact on how long it

took for the second revascularisation to be needed. For example,

it took 138 months (about 11.5 years), 46 months (nearly four

years) and 18 months for patients who received CABG, BMS

and DES, respectively, to require the second revascularisation.

Discussion

The main findings of this study indicate that OMT is pivotal

in the management of stable angina pectoris. This is in support

of several recent studies that have shown that there were no

differences between PCIs and OMT with regard to the all

major outcomes in patients with stable angina pectoris.

21

What

is more exciting and novel about our findings, in addition to

corroborating other recent findings such as those reported by

Iqbal

et al.

, is that OMT reduces the need for subsequent PCIs

when used before or together with an appropriate surgical

intervention(s).

22

More importantly, this study has shown that

OMT lengthens the period between surgical interventions.

However, the average age (65 years) of patients in this study

might have played a role in these findings. Recently, Won and

colleagues reported that PCIs were more beneficial than OMT

in patients with stable angina pectoris, aged 75 to 85 years old.

23

It was regrettable, as shown by the findings of our study,

that 75% of patient aged 65 years old (on average), who might

have benefited immensely, were not treated with OMT as the

initial management approach. Furthermore, the use of OMT

in this study was significantly less than the 44% reported in

the COURAGE study.

19

However it was much better than the

17% reported from the New York State Registry.

21

Therefore,

it means that the vast majority of medical practitioners in

private healthcare settings in South Africa still prefer surgical

interventions as the initial management approach for stable

angina pectoris, although there is strong evidence to the contrary.

The barriers to effective implementation of clinical guidelines

and their uptake into routine clinical practice are well documented

worldwide.

24,25

For example, Grol and Grimshaw reported that

absence of facilities, lack of feasibility, old routines, heavy

work-load, as well as no immediate risk of consequences for

non-compliance were the main barriers for poor implementation

of evidence.

26

The latter offers a possible explanation for the lack of

implementation of the findings of the COURAGE trial

19

in

private healthcare settings in South Africa, as reported in

this study. In these settings, there are generally no immediate

consequences for medical practitioners not adhering to

clinical guidelines. This happens because other than the strict

requirements set by medical aid schemes in South Africa, mostly

each medical practitioner relies on his/her own expert judgement.

More importantly, ‘professional pride and payer profit’ have a

big impact on ‘perspectives on optimal care and the best method

for improving health care’.

27

Therefore, it is also possible that OMT was less favoured

in private healthcare settings because of its minimal financial

benefits for medical practitioners, compared to surgery. As a

result, the majority of cardiologists in private healthcare settings,

as was recently reported by Mohee and Wheatcroft, continue to

underestimate the benefits of OMT in patients with stable angina

pectoris.

28

There are some limitations to this study. As it often the case

with other retrospective studies, there were missing data from

the files of patients studied. Most notably, we could not assess

the impact OMT on survival because of missing mortality data.

However, there is a low prevalence of mortality due to stable

angina pectoris.

29,30

Therefore it is unlikely that lack of data on

survival rates in the population studied had a significant impact

on the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Compelling evidence suggests that OMT should be the initial

management approach in patients with stable angina. Therefore

a reasonable approach is to optimise OMT and reserve coronary

revascularisation for mainly older patients who are sub-optimally

controlled on medical therapy, or for patients who are at high

risk of major adverse cardiac events.

References

1.

Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A.

Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income

countries.

Curr Problems Cardiol

2010;

35

(2): 72–115.

2.

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman

M,

et al.

; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke

OMT

SOMT

No medication

Period (in months)

80

60

40

20

0

*

p

<

0.05

*

*

Fig. 1.

Period (in months) it took for groups of patients with

stable angina to require second surgical intervention.

OMT: optimal medical therapy; SOMT: sub-optimal

medical therapy.