CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 5, September/October 2019

AFRICA

255

patients with constrictive pericarditis out of a sample size of

3 847 undergoing pericardiectomy.

In keepingwith other studies fromdeveloping countries,

2,11,12,19-21

and in contrast to Western series,

22,23

tuberculosis was the

major aetiology of constrictive pericarditis in our study and

highlights the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in refuelling a

resurgence of tuberculosis infections.

24,25

Similar to other series,

2,15

proven tuberculosis (pericardial histology, culture of AFB from

sputum, lymph nodes) was documented in 22 (26.5%) of the

patients. In contrast to Reuter’s findings in TB pericarditis,

26

we

found histological evidence of definite tuberculosis in only nine

operative pericardial biopsy specimens and could not determine

from these small numbers whether histological evidence of

tuberculosis is more common in HIV-positive subjects. The

natural history of tuberculous pericarditis has been previously

described, including treatment options to prevent progression to

constriction.

16,27-30

In this study we found few differences in the clinical profile

between HIV-positive and -negative patients. The higher levels

of alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transferase among

HIV-positive patients might have been due to hepatic tuberculosis

or more likely to more severe hepatic congestion in these subjects.

Importantly, there was no difference in the pre-operative and

follow-up ejection fraction between HIV-positive and -negative

patients. This finding differs from studies in patients with

tuberculous pericarditis co-infected with HIV who have been

found to have a higher prevalence of myopericarditis.

27,31

Preservation of ejection fraction might explain why we

found no significant differences in peri-operative mortality

rate observed between HIV-positive and -negative patients. It

is also likely that antiretroviral therapy in our patients may

have helped to preserve left ventricular function by preventing

the development of opportunistic infections or HIV-associated

myocardial dysfunction.

Pericardial calcification was identified on chest radiography

in 17 (20.5%) of our study patients, which is much higher than

the 5% reported by Strang

et al

. in the pre-HIV era.

19

While

equivalent rates of pericardial calcification in HIV-positive and

-negative patients (21.4 vs 20.7%;

p

=

0.953) have been described

in the study by Mutyaba

et al

.,

2

we found that calcification was an

uncommon finding in HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative

patients (6.3 vs 29.4%;

p

=

0.011). Furthermore none of the eight

patients with CD4 counts

<

200 cells/mm

3

developed pericardial

calcification.

We attributed the higher prevalence of pericardial calcification

among HIV-negative patients to longer survival in these patients

with a more prolonged duration of infection, progressing to

fibrosis and calcification. Alternatively it could be explained by

the suppression of CD4 helper by the HI virus, leading to less

fibrogenesis and calcification in these subjects.

26

Among the 31 subjects who did not undergo early surgery,

15 patients on telephonic contact were still alive, and of these,

five reported improvement in their symptoms (survival status

unknown in two) on anti-tuberculous therapy. Strang

et al

.

32

have shown that a significant number of patients diagnosed with

tuberculous constrictive pericarditis may undergo resolution

of their symptoms on anti-tuberculous therapy. The high

pre-operative mortality rate of 16.78% in our study emphasises the

importance of pericardiectomy in ensuring a successful outcome

in subjects who do not respond to anti-tuberculous therapy.

Our analysis of the pre-operative outcome showed that

HIV status had no effect on the pre-operative mortality rate

in constrictive pericarditis in subjects on antiretroviral therapy.

Instead, our analysis showed that older age, unsuppressed viral

load, lower serum haemoglobin and albumin levels, as well as

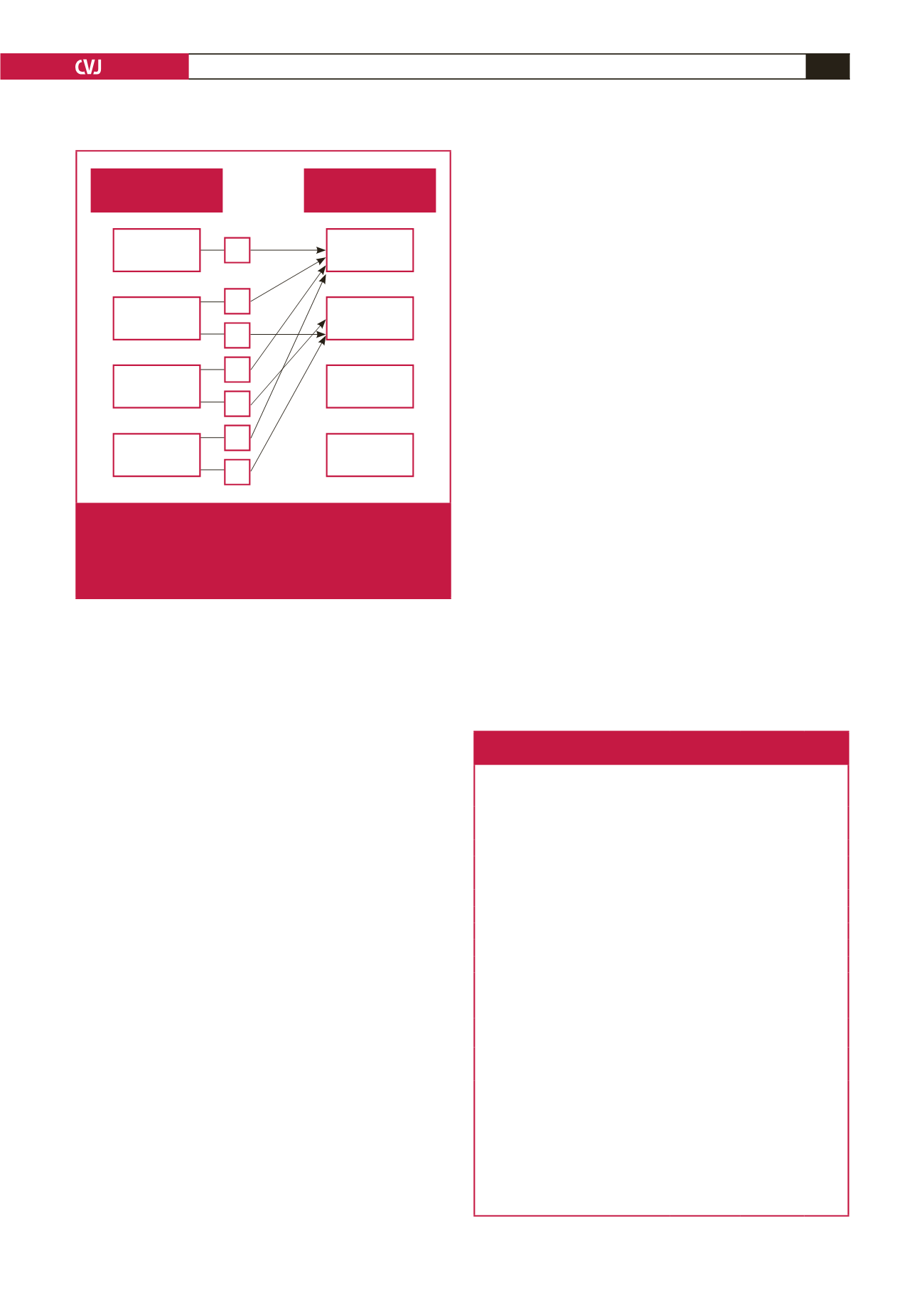

Six-week post-operative

NYHA class

Pre-operative NYHA class

NYHA I

n

=

3

NYHA I

n

=

33

2

21

NYHA II

n

=

9

NYHA II

n

=

53

6

10

NYHA III

n

=

22

NYHA III

n

=

0

1

NYHA IV

n

=

0

NYHA IV

n

=

5

1

1

Fig. 2.

Comparison of pre-operative and six-week postop-

erative New York Heart Association functional class

status in 41 patients (

p

<

0.0001). Most subjects

improved by at least one functional class. NYHA, New

York Heart Association.

Table 3. Operative characteristics of study patients stratified

by HIV status

Characteristic

All (

n

=

52)

HIV

negative

(

n

=

32)

HIV

positive

(

n

=

20)

p-

value

Pericardiectomy

0.093

Total

38 (73.1)

26 (81.3)

12 (60.0)

Sub-total

9 (17.3)

2 (6.3)

7 (35.0)

Not known

5 (9.6)

4 (12.5)

1 (5.0)

Inotrope usage

48 (94.1)

31 (96.9)

17(85.0)

0.547

Days in ICU

4.59

±

2.84 4.28

±

2.74 5.11

±

2.84 0.321

Postoperative complications 15 (28.9)

6 (18.8)

9 (45.0)

0.030

Pericardial histology

Granulomas

9 (18.4)

4 (12.9)

5 (27.8)

0.259

Acid-fast bacilli

3 (6.1)

1 (3.2)

2 (11.1)

0.546

Calcification

12 (24.4)

10 (32.3)

2/18 (11.1) 0.168

Postoperative ejection

fraction

53.55

±

6.65 53.33

±

6.70 53.93

±

6.79 0.783

Postoperative six-week

follow up

0.687

NYHA l

33 (80.4)

20 (76.9)

13 (86.7)

NYHA ll

9 (21.4)

6 (23.1)

2 (18.8)

Ejection fraction

53

±

9.16 52.44

±

11.50 53.83

±

4.67 0.785

Data presented as mean

±

standard deviation for continuous variables and

n

(%)

for categorical variables.

ICU, intensive care unit; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Details of inotrope usage was not available for one subject; three subjects’

histology results were not found (one HIV negative, two HIV positive); nine

subjects did not have postoperative measurement of ejection fraction (four HIV-

negative subjects and five HIV-positive subjects); 41 patients attended six-week

follow up (26 HIV negative, 15 HIV positive). Follow up ejection fraction (10

HIV-negative, five HIV-positive patients).