CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 2, March/April 2016

76

AFRICA

Conclusion

The exact aetiology of PE remains elusive but much of the

pathophysiology has been explained. The current theory is one

of balance between angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors.

Measurement of circulatory angiogenic and anti-angiogenic

proteins as biomarkers could possibly indicate placental

dysfunction and differentiate PE from other disorders, such as

gestational hypertension and chronic glomerulonephritis. In

addition, biomarkers such as those stated above are reproducible,

linked to the disease, and above all, are easy to interpret.

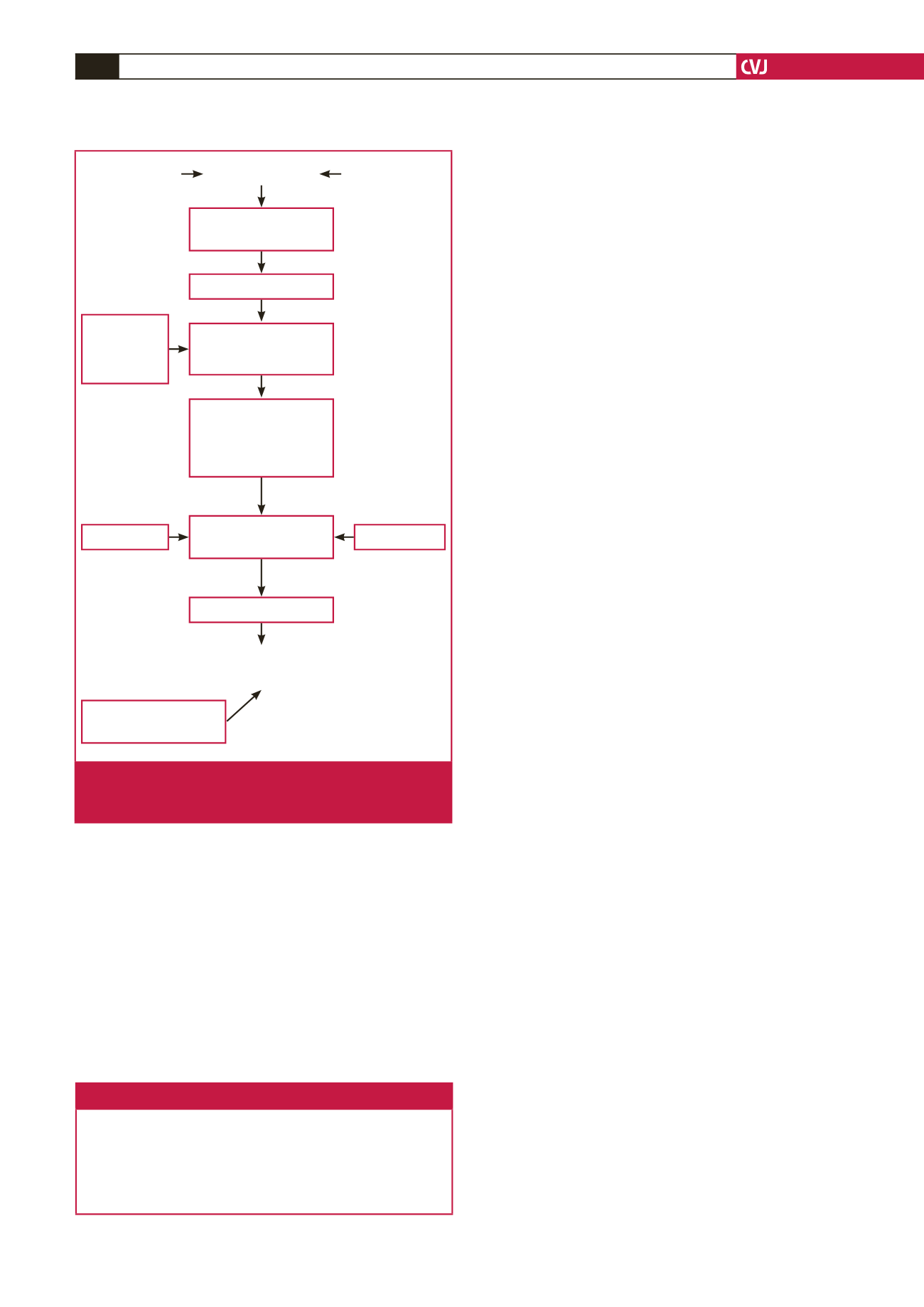

See Fig. 1 for some aspects of the pathophysiology of

pre-eclampsia.

Key messages

• The exact aetiology of pre-eclampsia remains elusive.

• Much of the pathophysiology has been explained.

• Treatment remains empirical and cure is dependent on stabilisa-

tion of high blood pressure and other specific organ complications,

followed by delivery of the foetus and placenta.

References

1.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Task force on

hypertension in pregancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2013. http://www.

acog.org/Resources_And_Publications/Task_Force_and_Work_Group_Reports/Hypertension_in_Pregnancy (accessed 2 June 2014).

2.

O’Tierney-Ginn PF, Lash GE. Beyond pregnancy: modulation of

trophoblast invasion and its consequences for fetal growth and long-

term children’s health.

J Reprod Immunol

2014;

104–105

: 37–42.

3.

Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T. Preeclampsia: a link between tropho-

blast dysregulation and an antiangiogenic state.

J Clin Invest

2013;

123

(7): 2775–2777.

4.

Staff AC, Benton SJ, von Dadelszen P,

et al

. Redefining preeclampsia

using placenta-derived biomarkers.

Hypertension

2013;

61

(5): 932–942.

5.

von Dadelszen P, Magee LA, Roberts JM. Subclassification of preec-

lampsia.

Hypertens Pregnancy

2003;

22

(2): 143–148.

6.

Huppertz B. Placental origins of preeclampsia: challenging the current

hypothesis.

Hypertension

2008;

51

(4): 970–975.

7.

Sohlberg S, Mulic-Lutvica A, Lindgren P, Ortiz-Nieto F, Wikstrom AK,

Wikstrom J. Placental perfusion in normal pregnancy and early and

late preeclampsia: a magnetic resonance imaging study.

Placenta

2014;

35

(3): 202–206.

8.

Valensise H, Vasapollo B, Gagliardi G, Novelli GP. Early and late pre-

eclampsia: two different maternal hemodynamic states in the latent

phase of the disease.

Hypertension

2008;

52

(5): 873–880.

9.

Zhong Y, Tuuli M, Odibo AO. First-trimester assessment of placenta

function and the prediction of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth

restriction.

Prenatal Diagn

2010;

30

(4): 293–308.

10. Verdonk K, Visser W, Van Den Meiracker AH, Danser AH. The renin-

angiotensin-aldosterone system in pre-eclampsia: the delicate balance

between good and bad.

Clin Sci (Lond)

2014;

126

(8): 537–544.

11. Williams DJ, Vallance PJ, Neild GH, Spencer JA, Imms FJ. Nitric oxide-

mediated vasodilation in human pregnancy.

Am J Physiol

1997;

272

(2

Pt 2): H748–752.

12. Salas SP, Marshall G, Gutierrez BL, Rosso P. Time course of maternal

plasma volume and hormonal changes in women with preeclampsia or

fetal growth restriction.

Hypertension

2006;

47

(2): 203–208.

13. Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K,

et al.

Vascular endothelial growth

factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast

survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated

liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome.

Am J Pathol

2002;

160

(4):

1405–1423.

14. Valenzuela FJ, Perez-Sepulveda A, Torres MJ, Correa P, Repetto

GM, Illanes SE. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia: the genetic compo-

nent.

J Pregnancy

2012; Article ID: 632732: 8 pages.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/632732.

15. Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The “Great

Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placenta-

tion.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

2011;

204

(3): 193–201.

16. Foidart JM, Schaaps JP, Chantraine F, Munaut C, Lorquet S.

Dysregulation of anti-angiogenic agents (sFlt-1, PLGF, and sEndoglin)

in preeclampsia – a step forward but not the definitive answer.

J Reprod

Immunol

2009;

82

(2): 106–111.

17. Whitley GS, Cartwright JE. Cellular and molecular regulation of spiral

artery remodelling: lessons from the cardiovascular field.

Placenta

2010;

31

(6): 465–474.

18. Moffett A, Colucci F. Uterine NK cells: active regulators at the mater-

nal–fetal interface. J C

lin Invest

2014;

124

(5): 1872–1879.

19. Redman CW, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal

inflammatory response to pregnancy.

Am J Obstet Gynecol

1999;

180

(2

Pt 1): 499–506.

uNKC

Placental ischaemia

Defective spiral

artery remodelling

Cytotrophoblasts Genetic factors

↑

sFlt-1

Endothelial

dysfunction

Glomerular

endotheliosis

Hypoxia–reperfusion

damage of

trophoblasts

HYPERTENSION,

PROTEINURIA,

OEDEMA

Pulsatile/

intermittent

blood flow

to placenta

STMBs, cytokines,

AT-1AA, imbalance

in angiogenic–anti-

angiogenic factors in

maternal circulation

↓

VEGF, PlGF

PRE-ECLAMPSIA

Fig. 1.

Aspects of pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia. VEGF:

vascular endothelial growth factor; PlGF: placental

growth factor; sFlt-1: soluble film-like tyrosine kinase.