CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 4, July/August 2016

AFRICA

249

and in the final model the strongest predictor among them was

log-RDW.

We know that increased body fat mass can lead to

atherosclerotic vascular diseases.

2

If there is no evidence of

cardiovascular disease or disorders such as hypertension,

hyperlipidaemia and diabetes in overweight or obese individuals,

they are not treated with medication, but lifestyle changes are

suggested.

16

Despite this, cardiovascular events appear more

frequently in the obese population than in individuals with a

lower BMI.

1

In this study, we speculated that RDW may be used to

determine persons at high risk for atherosclerosis among

obese and overweight individuals without overt cardiovascular

disorders. Thus individuals who are prone to atherosclerosis

could more easily be identified using RDW and more closely

followed up.

RDW, which is usually overlooked and almost only used in

the differential diagnosis of anaemia in daily practice, is typically

raised in some cardiac and non-cardiac conditions, such as

coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, acute coronary

syndromes, heart failure, malnutrition, neoplastic metastases to

bone marrow and inflammatory bowel disease.

7,17-19

RDW generally reflects ineffective red cell production or their

increased rate of destruction. However, it has been demonstrated

that oxidative stress and chronic inflammation also cause elevated

RDW. By destruction of the erythrocytes, haemolytic conditions

lead to elevation of RDW, and impaired erythropoiesis,

haemoglobinopathies, folic acid or cyanocobalamin deficiency,

and iron deficiency also cause raised RDW.

19,20

On the other hand, inflammatory cytokines have an effect on

iron metabolism and the production or activity of erythropoietin.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations and regression analyses

(stepwise) of aortic PWV with related parameters

Parameters

Bivariate

correlation

Stepwise regression analyses

Model I

(

R

2

=

0.304)

Model II

(

R

2

=

0.456)

Model III

(

R

2

=

0.492)

R p

β

p

β

p

β

p

Aortic PWV

Log-RDW 0.469

<

0.001 0.551

<

0.001 0.506

<

0.001 0.457

<

0.001

Resting

heart rate 0.417

<

0.001

0.393

<

0.001 0.421

<

0.001

Age

0.188 0.022

0.196 0.003

BMI

0.223 0.007

WHR 0.128 0.174

For regression analyses of aortic PWV; predictors in model I: log-RDW; predic-

tors in model II: log-RDW and resting heart rate; predictors in model III: log-

RDW, resting heart rate and age.

Aix75: augmentation index 75; BMI: body mass index; PWV: pulse-wave veloc-

ity; RDW: red cell distribution width; WHR: waist–hip ratio.

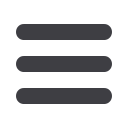

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

0.95 1.00 1.05 1.10 1.15 1.20 1.25

Log-RDW

Pulse wave velocity, m/s

n

=

149

β

=

0.469

p

<

0.001

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

60

80

100

120

Heart rate, beats per minute

Pulse wave velocity, m/s

n

=

149

β

=

0.417

p

<

0.001

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

20

40

60

80

Age, years

Pulse wave velocity, m/s

n

=

149

β

=

0.188

p

<

0.022

1.25

1.20

1.15

1.10

1.05

1.00

0.95

15 20 25 30 35 40

Body mass index, kg/m

2

Log-RDW

n

=

149

β

=

0.239

p

<

0.004

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot showing correlations of related parameters with each other. Aortic PWV with log-RDW (A), heart rate (B), age

(C), and log-RDW with BMI (D). BMI: body mass index; PWV: pulse-wave velocity; RDW: red cell distribution wave.

C

A

D

B