CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 4, July/August 2016

e18

AFRICA

was awake and conscious at about postoperative hour four. A

subsequent neurological examination revealed no pathology and

the patient was extubated.

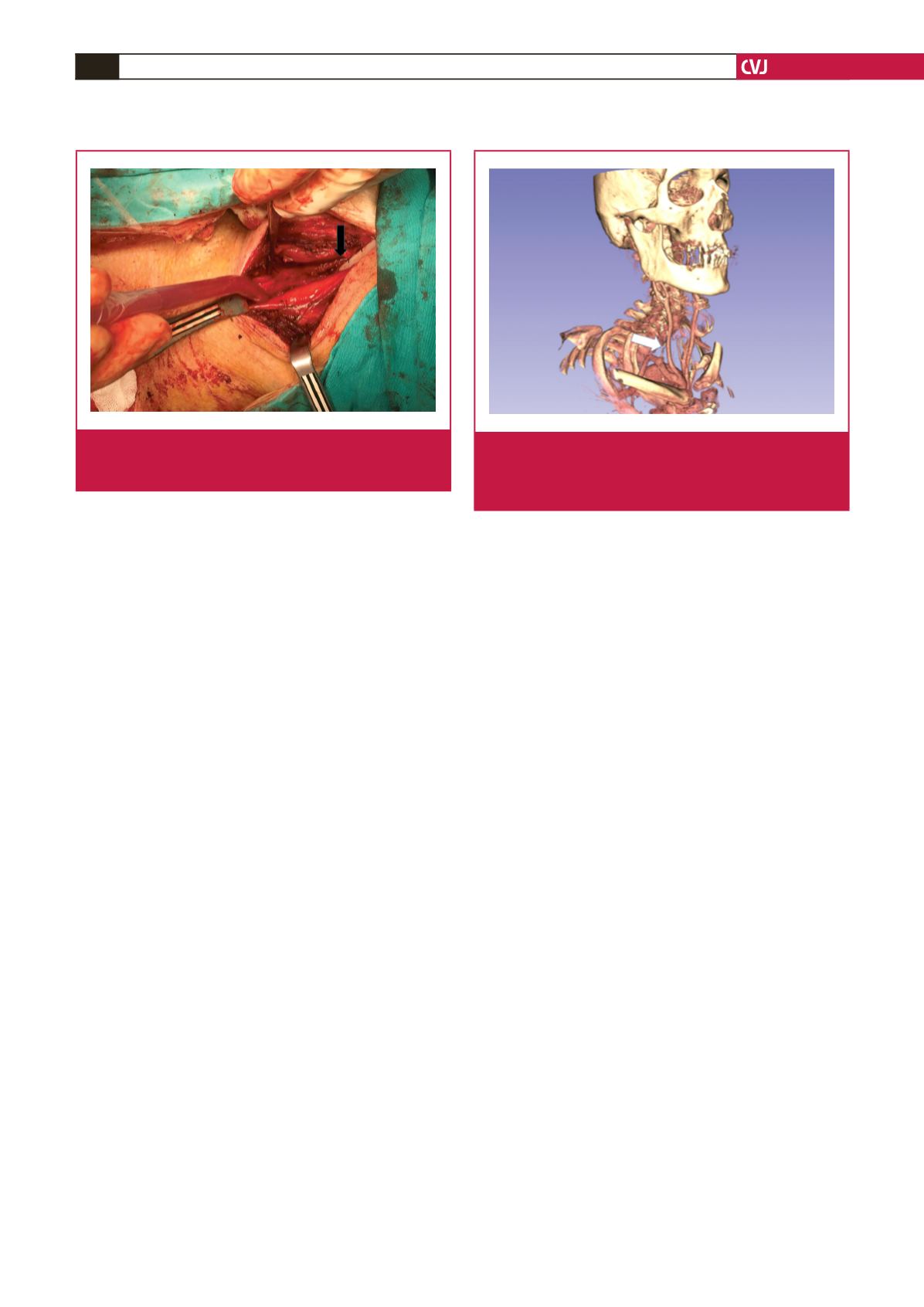

Tomographic angiography performed postoperatively

revealed that the right vertebral artery was present at the outlet

but totally occluded from about 0.5 cm (Fig. 2). The patient

was again examined neurologically but no neurological deficit

was identified. It was therefore recommended that he continue

his treatment of low-molecular-weight heparin. His cardiac

medication and other medical treatment were planned and he

was discharged on condition of follow-up visits.

Discussion

Internal jugular vein catheterisation is preferred in patients

undergoing open-heart surgery, since it is easy to cannulate

and is associated with a reduced risk of complications during

cannulation; it is also distant from the surgical site. The

prevalence of vertebral artery cannulation during internal

jugular vein catheterisation is unknown, probably because there

are fewer cases reported than actually occur. When we reviewed

the literature, it was found to be reported less often than carotid

artery punctures. Carotid artery puncture during internal jugular

vein cannulation has been reported at a rate of 0.5 to 11.4%,

whereas the rate of vertebral artery cannulation was from 0.099

to 0.775%,

2

and fewer than 30 cases were reported on iatrogenic

vertebral artery cannulation.

3

Dissection, thrombosis, formation of arteriovenous fistulae,

and pseudo-aneurysms are complications of vertebral artery

injury during vein cannulation.

3

Diagnosis of pseudo-aneurysm

of the vertebral artery is often delayed because symptoms occur

only late after cannulation.

4

In particular, some patients may

develop fatal vertebrobasilar ischaemia due to vertebral artery

cannulation and associated severe and damaging sequelae, such

as stroke or visual defects, while others may be asymptomatic,

which can be attributed to sufficient extracranial collateral

circulation.

5

The best way to avoid iatrogenic vertebral artery cannulation is

to take the necessary precautions. In other words, the best way to

perform this procedure is under the guidance of ultrasonography,

as recommended in many guidelines. However, this is almost

impossible in emergent cases and when ultrasonography is not

available or is difficult to access. In such cases, intervention may

be performed using anatomical reference points.

The vertebral artery is classically the first branch of the

ipsilateral subclavian artery, and arises from the posterior–

superior part of this artery. The vertebral artery, after separating

from the subclavian artery, generally passes through the

transverse process of the C7 vertebra and superiomedially enters

the transverse foramen of the cervical vertebrae (C6 in 95% of

cases), extending vertically to the level of the C2 vertebra within

the transverse foramen of the vertebrae.

6

The extraforaminal

region is about 4 cm and located deeper and more medially than

the internal jugular vein. It is the region most open to injury, and

in this region it is difficult to stop haemostasis with compression,

7

because the vertebral artery courses in a deep plane.

A safer approach when arterial damage is caused, is with

an immediate surgical or endovascular stent application by

a wide-scale catheter, as stated by Hong-liang

et al

.

8

These

kinds of punctures frequently result from hyperextension of

the neck, accompanied by excessive rotation of the head, or

failure to adjust the direction and depth of the puncture, or

using an excessively long needle to perform the puncture. In

addition, the non-pulsatile flow from the first puncture, due to

the thinner diameter of the vertebral artery, may be misleading.

Both the quantity and colour of the flow are manifested more

clearly when the final tip reaches the subclavian artery following

catheterisation, as in our case.

Conclusion

It should always be considered that during percutaneous

interventions, vertebral artery cannulation may occur, even if

there is only a slight probability. In the event of such a case,

there should be a management plan, previously prepared by the

surgeon and anaesthetists. If endovascular repair is not possible

in vertebral artery catheterisations, or if the artery is completely

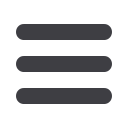

Fig. 1.

After foraminectomy the catheter was clearly seen

advancing through the vertebral artery. The black

arrow shows the side of the catheter.

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional tomographic angiography show-

ing the right vertebral artery was present at the outlet

but totally occluded for about 0.5 cm. The white arrow

shows the right vertebral artery and the occluded part.