CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 6, November/December 2018

348

AFRICA

with hypertension in South Africa and call for interventions to

address gaps in CV-risk screening and management, especially

that each additional CV risk exponentially increases the risk of

CVD in a patient with hypertension.

28

Since most CV risk factors are modifiable, lowering BP alone

without intervening in co-existing CV risk factors can therefore

not be deemed optimal care. Regrettably, only four to 7% of

patients with multiple CV risk factors receive appropriate risk-

management interventions during clinical encounters,

12

signifying

enormous missed clinical opportunities and the need for strategies

to close this gap. Such strategies should include academic detailing

of CV risk factors in the management of hypertension to improve

healthcare providers’ screening behaviours and prompt them to

initiate management for these risk factors. Even when the burden

of CV risk factors is assessed to be low, primary prevention

should still be done, since the prevalence of CV risks tends to

increase with age and if not attended, a relatively low burden of

CV risks in the present may translate into higher lifetime risks of

CVD in a patient with hypertension.

29

In line with other African studies,

24,30

this study found that

obesity is prevalent (65.8%) among patients with hypertension;

higher than reported in two recent nationally representative

population surveys in South Africa: SADHS 2016 (29.01%)

26

and SANHNES-1 (29.07%).

27

This is possibly due to clustering

of CV risk factors in patients with hypertension.

The concurrent high prevalence of increased abdominal

circumference (80.8%) in this study also reiterates the

substantially higher risk of CVD in this population compared to

the general population, especially since abdominal circumference

is a strong predictor of adverse CV outcomes. Measurement of

abdominal circumference should therefore form part of the vital

signs in patients with hypertension during clinic visits in PHC.

This is to ensure that healthcare providers respond to abnormal

values by counselling on the need for weight loss, healthy diets

and increased physical activity.

31-33

In addition, health education

needs to be offered to dispel cultural myths that purport obesity

as a symbol of wealth and wellbeing.

34

Physical inactivity is a leading cause of mortality and there is

a graded inverse relationship between physical activity and risk

of CVD.

33

In this study, most participants (73.2%) reported being

physically inactive (Table 3), far greater than the prevalence

reported in previous South African studies.

35,36

A Libyan study

has found a similar prevalence (74.5% among men and 75.5%

in women).

37

The implication of this finding is the enormous clinical

and financial burden it places on the ever-stretched healthcare

system in South Africa. This is dire, considering the relative risk

for developing hypertension in sedentary men and women with

normal BP at rest is 35 to 70% higher than in their physically

active peers.

38

It is therefore important that clinic visits in

primary care be used as opportunities to promote a physically

active lifestyle, especially among patients with one or more CV

risks. This is imperative in the light of the emerging epidemic of

non-communicable diseases in South Africa.

Pensioners, men, blacks and participants of lower socio-

economic status were significantly more likely to report being

physically inactive (Table 6). While previous studies in South

Africa have reported poor engagement of old people in regular

exercise,

39

the significantly higher odds of physical inactivity

among men (compared to women) is contrary to the literature

26,27

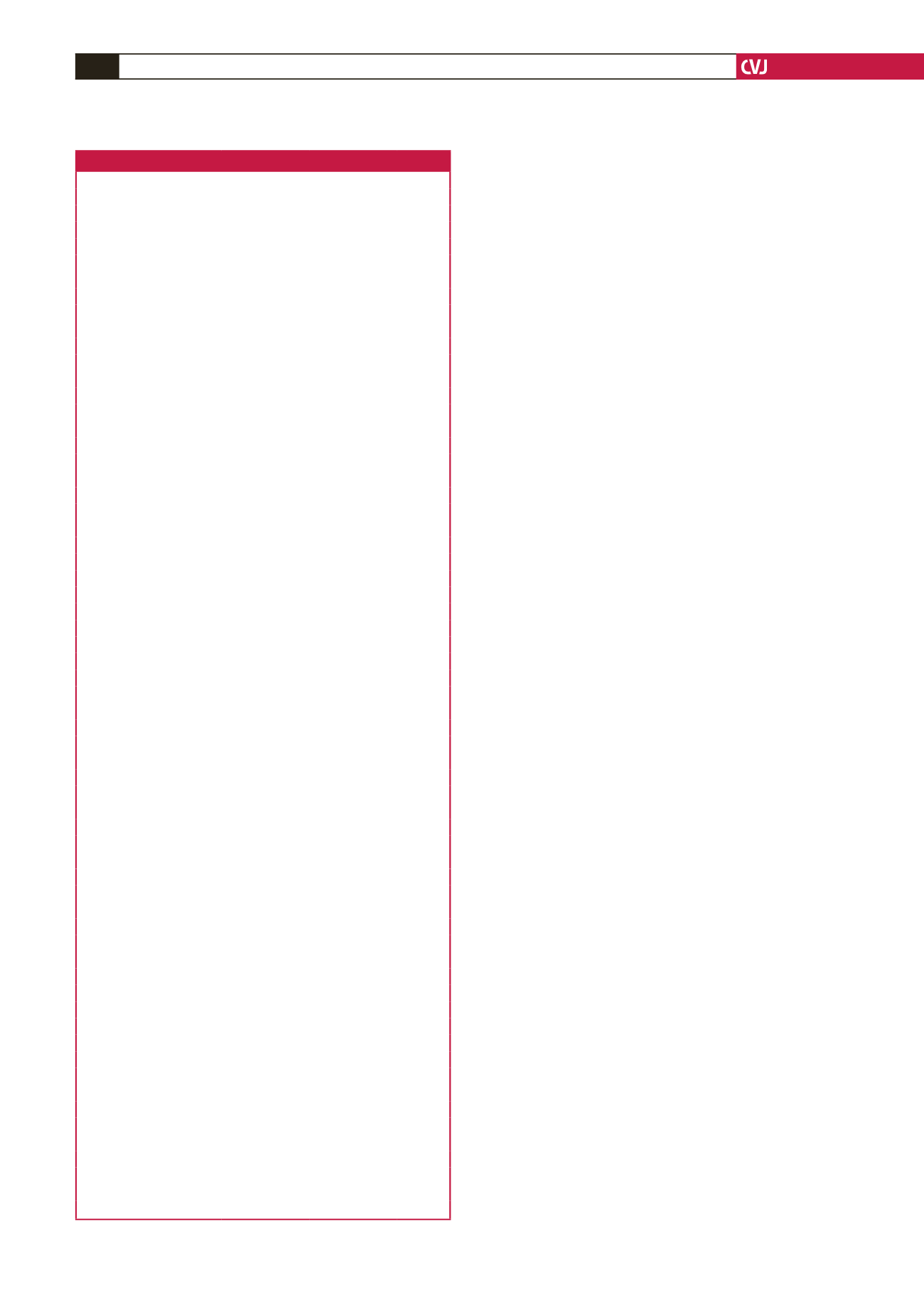

Table 6. Sociodemographic determinants of CV risk factors

Risk factor

Odds ratio

95% CI

p

-value

Alcohol use

Age group, years

20–39

1.00

40–59

0.2227

0.0723–0.6853 0.0088

60–79

0.1830

0.0581–0.5764 0.0037

80+

0.2119

0.0185–2.4242 0.2121

Gender

Female

1.00

Male

4.2939

2.3918–7.7088 0.0000

Cigarette smoking

Race

Other

1.00

Black

0.1543

0.0668–0.3567 0.0000

Gender

Female

1.00

Male

6.2782

2.7958–14.0980 0.0000

Current snuff use

Education level

Below secondary

1.00

Secondary or higher

0.6100

0.3376–1.1021 0.1015

Race

Other

1.00

Black

10.9513

1.4475–82.8551 0.0204

Gender

Female

1.00

Male

0.0477

0.0065–0.3520 0.0028

Physical inactivity

Age group, years

20–39

1.00

40–59

0.6033

0.1806–2.0147 0.4114

60–79

0.8299

0.1753–3.9292 0.8141

80+

118865.6277 0.0000– > 1.0312 0.9641

Employment

Employed

1.00

Pensioner

3.4727

1.1946–10.0953 0.02

Unemployed

1.7198

0.9188–3.2192

0.10

Gender

Male

1.00

Female

0.4342

0.2162–0.8719

0.02

Diabetes mellitus

Gender

Female

1.00

Male

1.8634

1.0701–3.2448 0.0279

Hypercholesterolaemia

Race

Other

1.00

Black

0.3201

0.1131–0.9063 0.0319

Family history of hypercholesterolaemia

Race

Other

1.00

Black

0.1210

0.0296–0.4941 0.0033

Education

Below secondary

1.00

Secondary or higher

0.7258

0.1094–4.8153 0.7399

Family history of fatal CV event

Race

Other

1.00

Black

0.1210

0.0296–0.4941 0.0033

BMI > 30 kg/m

2

Gender

Female

1.00

Male

0.1859

0.1053–0.3283 0.0000