CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 30, No 3, May/June 2019

AFRICA

155

imperfection and that irreversible pulmonary vascular changes

may occur at under two years of age. This is most likely the after-

effect of the high-pressure pulsatile stream transmitted from the

aorta to the pulmonary artery throughout the cardiovascular

cycle in patients with PDA.

In our study, we found that PAP was significantly higher in

children with PDA prior to closure (

p

<

0.05) in both groups.

After closure, the PAP was diminished in both groups (

p

<

0.05)

and approaching non-significance compared with the control

group (

p

>

0.05) (Tables 3, 4). Additionally, we discovered a

significant positive relationship between ASI and PAP (

r

=

0.6,

p

<

0.05) (Fig. 2).

We also found in this study that the PAP was significantly

higher in patients in group B than in those in group A preceding

closure (

p

<

0.05). After closure, there was no significant

difference between groups with regard to PAP (

p

=

0.2) (Table 2).

Note that a small number of patients with PDA and PAH and

marginal haemodynamic instability can deteriorate after PDA

closure because of non-regression of pulmonary hypertension,

progressive PVD and right heart failure. Therefore their normal

history becomes similar to that of primary or idiopathic PAH.

These patients have a better normal history if the PDA is left

untreated.

A safe examination to distinguish who may benefit from

PDA closure with long-term regression of PAH and who may

be plagued by progressive pulmonary vascular disease and right

heart failure is presently not available. Future research on the type

and degree of morphological changes in the pulmonary vessels,

individual inconsistence, and hereditary and epigenetic variables

may provide some insight into this disturbing problem. Until

such time, in clinical practice, infrequently there may be a patient

who will not benefit from closure of an expansive PDA and may

have an adverse outcome if PDA closure is attempted; however

there may be many others who have favourable outcomes.

Aortic stiffening prompts faster pulse wave velocity, and

therefore a prior heartbeat wave reflection may occur, bringing

about an expansion in focal systolic blood pressure (SBP)

and a diminishing diastolic blood pressure (DBP) with an

increment in pulse pressure. An expanded SBP may build the LV

afterload, with an expansion in myocardial oxygen demand, LV

hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inevitably, a reduction in the LVEF.

19

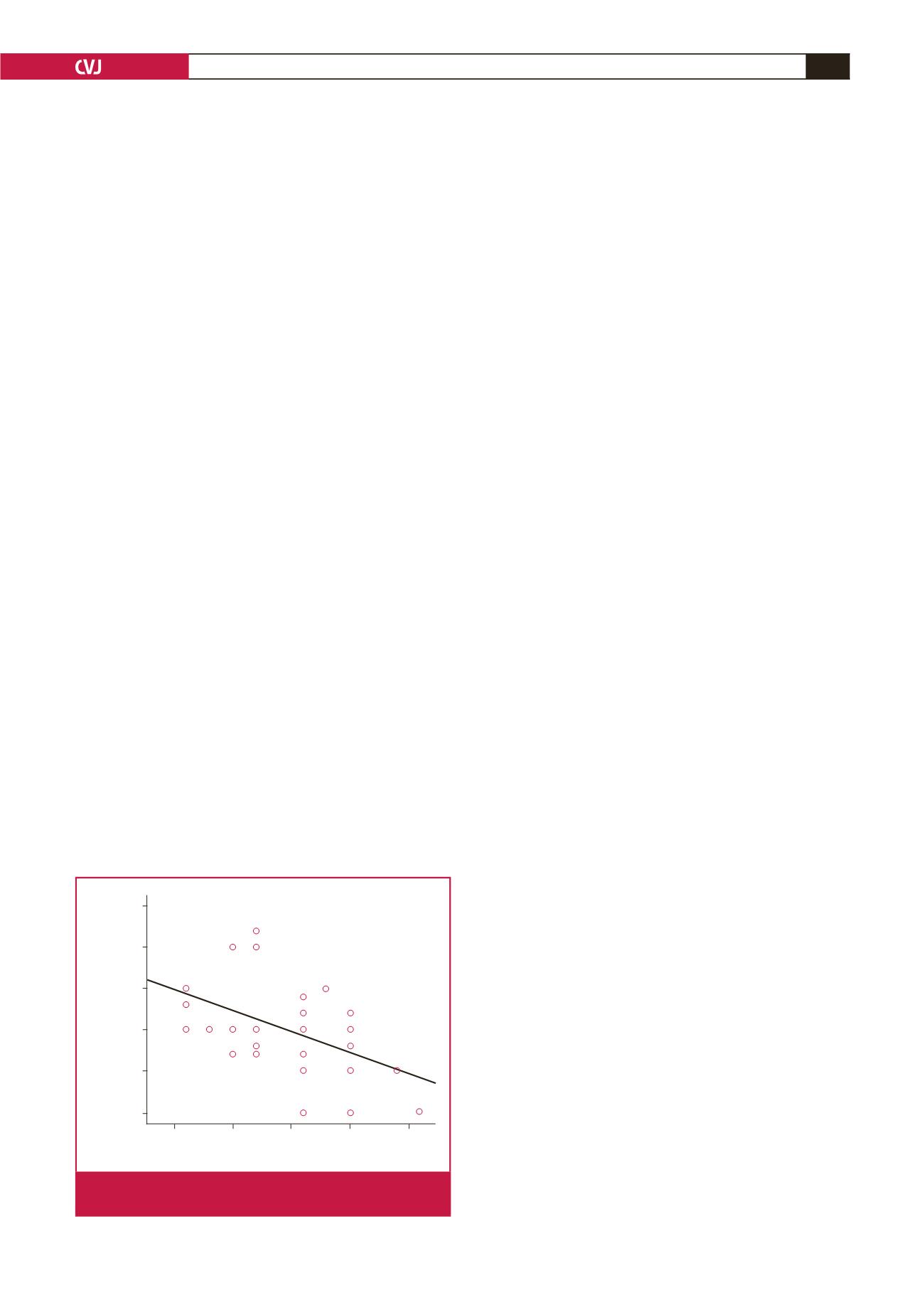

In our study, we found a significant negative correlation between

the ASI and LVEF prior to PDA closure (

r

=

0.66,

p

<

0.05)

(Fig. 4) and a significant positive relationship between ASI and

LVEDD prior to closure (

r

=

0.58,

p

<

0.05) (Fig. 3).

Conclusion

Aortic stiffness is increased in patients with PDA, even in cases

of small-sized PDAs and is related to weakness in heart function,

especially if PDA closure is deferred to after the age of one year.

After device closure, the ASI diminished significantly and was

associated with a notable change in heart capacity and functional

class months after device closure. The ASI may be helpful in

assessing the course of patients with PDA prior to and after

intervention. We recommend early closure of PDA, even in cases

of small-sized PDAs, and use of the ASI as a tool for following

patients with PDA before and after closure.

References

1.

Samanek M. Children with congenital heart disease: probability of

natural survival.

Pediatr Cardiol

1992;

13

(3): 152–158. DOI: 10.1007/

bf00793947.

2.

Gkaliagkousi E, Douma S. The pathogenesis of arterial stiffness and its

prognostic value in essential hypertension and cardiovascular diseases.

Hippokratia

2009;

13

(2): 70–75. PMID: 19561773.

3.

Mahfouz RA, Dewedar A, Abdelmoneim A, Hossien EM. Aortic and

pulmonary artery stiffness and cardiac function in children at risk for

obesity.

Echocardiography

2012;

29

(8): 984–990. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-

8175.2012.01736.x.

4.

Yandle TG, Richards AM, Gilbert A, Fisher S, Holmes S, Espiner EA.

Assay of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in human plasma: evidence

for high molecular weight BNP as a major plasma component in heart

failure.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab

1993;

76

(4): 832–838. DOI: 10.1210/

jcem.76.4.8473392.

5.

Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery JL, Barbera

JA,

et al

. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary

hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of

Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the

International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT).

Eur

Heart J

2009;

30

(20): 2493–2537. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297.

6.

Yang SW, Zhou YJ, Hu DY, Liu YY, Shi DM, Guo YH,

et al.

Feasibility

and safety of transcatheter intervention for complex patent ductus arte-

riosus.

Angiology

2010;

61

(4):372–376.DOI:10.1177/0003319709351874.

7.

Jekell A, Malmqvist K, Wallen NH, Mortsell D, Kahan T. Markers of

inflammation, endothelial activation, and arterial stiffness in hyperten-

sive heart disease and the effects of treatment: results from the SILVHIA

study.

J Cardiovasc Pharmacol

2013;

62

(6): 559–566. DOI: 10.1097/

fjc.0000000000000017.

8.

Park S, Lakatta EG. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of

arterial stiffness.

Yonsei Med J

2012;

53

(2): 258–261. DOI:10.3349/

ymj.2012.53.2.258.

9.

Malayeri AA, Natori S, Bahrami H, Bertoni AG, Kronmal R, Lima

JA,

et al

. Relation of aortic wall thickness and distensibility to cardio-

vascular risk factors (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

[MESA]).

Am J Cardiol

2008;

102

(4): 491–496. DOI: 10.1016/j.

amjcard.2008.04.010.

ASI

2.5

5.0

7.5

10.0

12.5

LVEF

75

70

65

60

55

50

r

= 0.575

p

= 0.001**

Fig. 4.

A significant negative correlation is shown between

the ASI and LVEF.