CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 5, September/October 2020

248

AFRICA

proportion of study subjects had a history of percutaneous

coronary intervention (33.2%) and/or coronary artery bypass

grafting (21.0%). The most frequent cardiovascular risk factors

were hypertension (77.6%) and diabetes mellitus (64.4%). The

prevalence of diagnosed FH in this cohort was 20.6%.

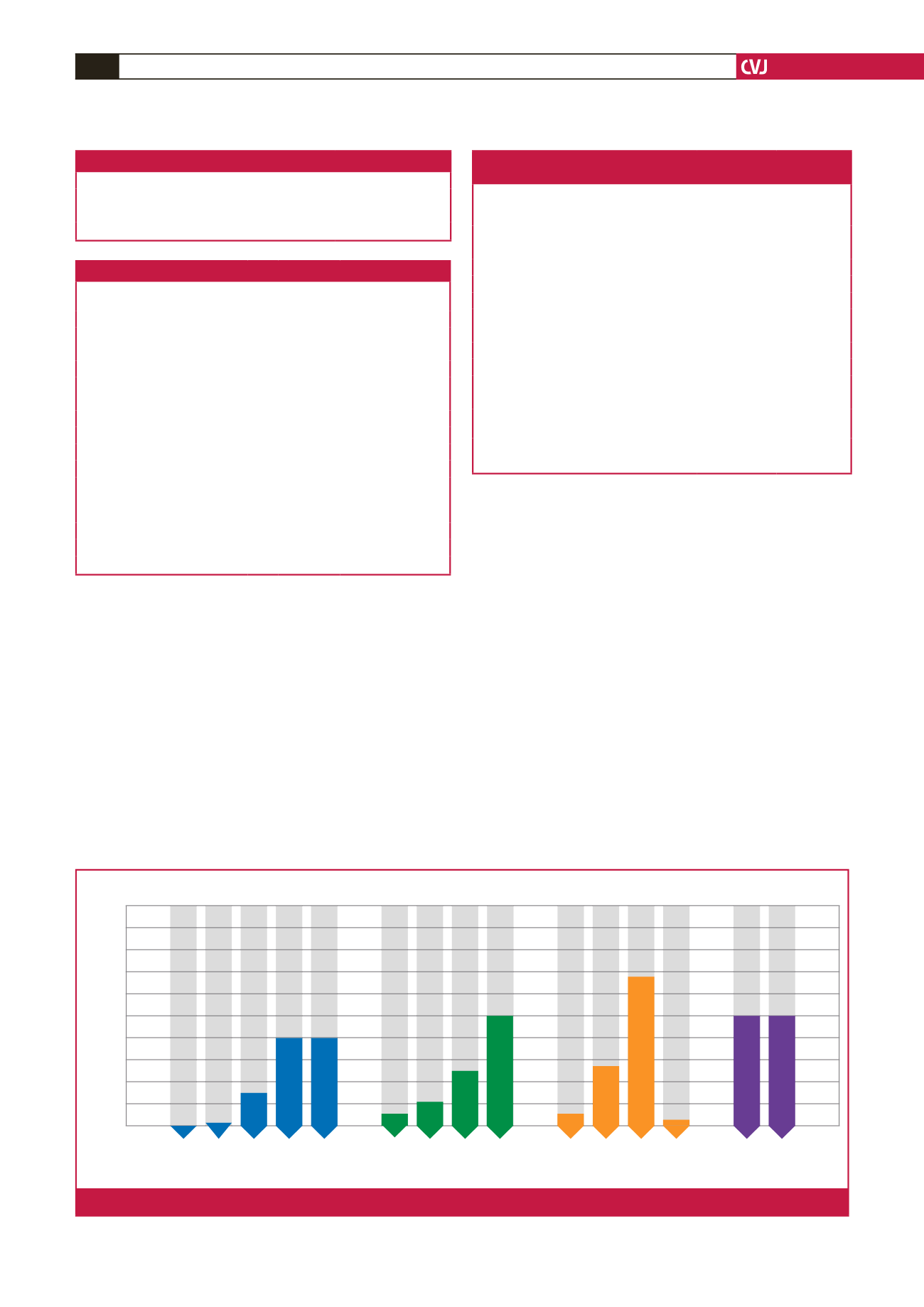

Most patients (50.0%) were taking atorvastatin, followed

by rosuvastatin (30.8%), simvastatin (18.8%) and pravastatin

(0.4%). All were on the maximum-tolerated dose of statin

therapy according to their physician’s assessment. The number

of patients on different statins is shown in Fig. 1.

Only 68 (13.8%) of the patients were prescribed ezetimibe and

none received ezetimibe monotherapy (Table 5). The reported

reasons for not using ezetimibe included that ezetimibe use was

not considered necessary by the prescribing physician (48.7%),

financial constraints relating to cost or reimbursement (31.7%),

physician choice (8.3%) and other (11.3%). Most patients

prescribed ezetimibe were also receiving high-intensity statin

therapy (atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg) and

were defined as the maximum-treatment group.

Only 161 of the 491 (32.8%) patients who were taking the

maximum-tolerated statin dose, with or without ezetimibe,

reached the LDL-C goal of

<

1.8 mmol/l. This percentage was

even lower (16.2%) in patients on ezetimibe. In the group of

maximally treated patients (high-dose statin plus ezetimibe) the

at-goal rate was 13.2%.

In the 330 patients not at LDL-C goal, the LDL-C level was

between 2.5 and 5.0 mmol/l in most patients (56.4%). Less than

20% (18.8%) of these patients were receiving maximal lipid-

lowering therapy. LDL-C level higher than 5 mmol/l despite

aggressive therapy was relatively uncommon and was found in

only 16 (4.8%) patients. More females than males (nine vs seven)

had an LDL-C level of

>

5 mmol/l on treatment, although our

study overall had recruited significantly more males than females.

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Percentage

5 mg 10 mg 20 mg 40 mg 80 mg

Atorvastatin

5 mg 10 mg 30 mg 40 mg

Rosuvastatin

10 mg 20 mg 40 mg 80 mg

Simvastatin

10 mg 80 mg

Pravastatin

Patients,

n

= 468*

n

= 1

n

= 2

n

= 36

n

= 98

n

= 97

n

= 7

n

= 15

n

= 51

n

= 71

n

= 3

n

= 23

n

= 61

n

= 1

n

= 1

n

= 1

Fig. 1.

Statin doses (

n

=

468

*

).

Table 5. Ezetimibe use in the study population

Combination of ezetimibe and statin

(

n

=

68)

mg

Number (%)

Atorvastatin (

n

=

32)

10

2 (2.9)

20

1 (1.5)

40

2 (2.9)

80

27 (39.7)

Rosuvastatin (

n

=

25)

10

1 (1.5)

20

4 (5.9)

40

20 (29.4)

Simvastatin (

n

=

10)

20

5 (7.3)

40

5 (7.3)

Pravastatin (

n

=

1)

10

1 (1.5)

Maximum treatment group (

n

=

53) mg

Number

(%)

Reached LDL-C goal,

n

(%)

Ezetimibe + atorvastatin

40

2 (3.8)

1 (50.0)

80

27 (50.9)

2 (7.4)

Ezetimibe + rosuvastatin

20

4 (7.5)

1 (25.0)

40

20 (37.7)

4 (20.0)

Table 6. Patient characteristics stratified by

LDL-C

<

1.8 mmol/l (goal) and

>

5 mmol/l

Patient characteristics

LDL-C goal

(

<

1.8 mmol/l)

(

n

=

161)

LDL-C

>

5 mmol/l

(

n

=

16)

Gender,

n

(%)

Male

118 (73.2)

7 (43.7)

Female

43 (26.7)

9 (56.3)

Age mean (years), mean

±

SD

62.9

±

10.5

53.9

±

10.9

Ethnicity,

n

(%)

Black

34 (100.00)

0 (0.0)

Caucasian

48 (87.3)

7 (12.7)

Asian

72 (97.3)

2 (2.7)

Mixed

7 (50.0)

7 (50.0)

Duration of dyslipidaemia (years), mean

±

SD 10.9

±

7.4

14.3

±

11.6

Obesity (BMI

>

30 kg/m

2

),

n

(%)

72 (45.3)

6 (37.5)

Family history of premature atherosclerotic

disease,

n

(%)

33 (20.5)

6 (37.5)

Familial hypercholesterolaemia,

n

(%)

4 (2.5)

13 (81.3)

Diabetes mellitus,

n

(%)

121 (75.2)

6 (37.5)

Table 4. Family history of premature cardiovascular events (

n

=

491)

Family history

Number (%)

Coronary artery disease

133 (27.1)

Cerebrovascular disease

36 (7.3)

Peripheral artery disease

3 (0.6)