CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 32, No 4, July/August 2021

AFRICA

195

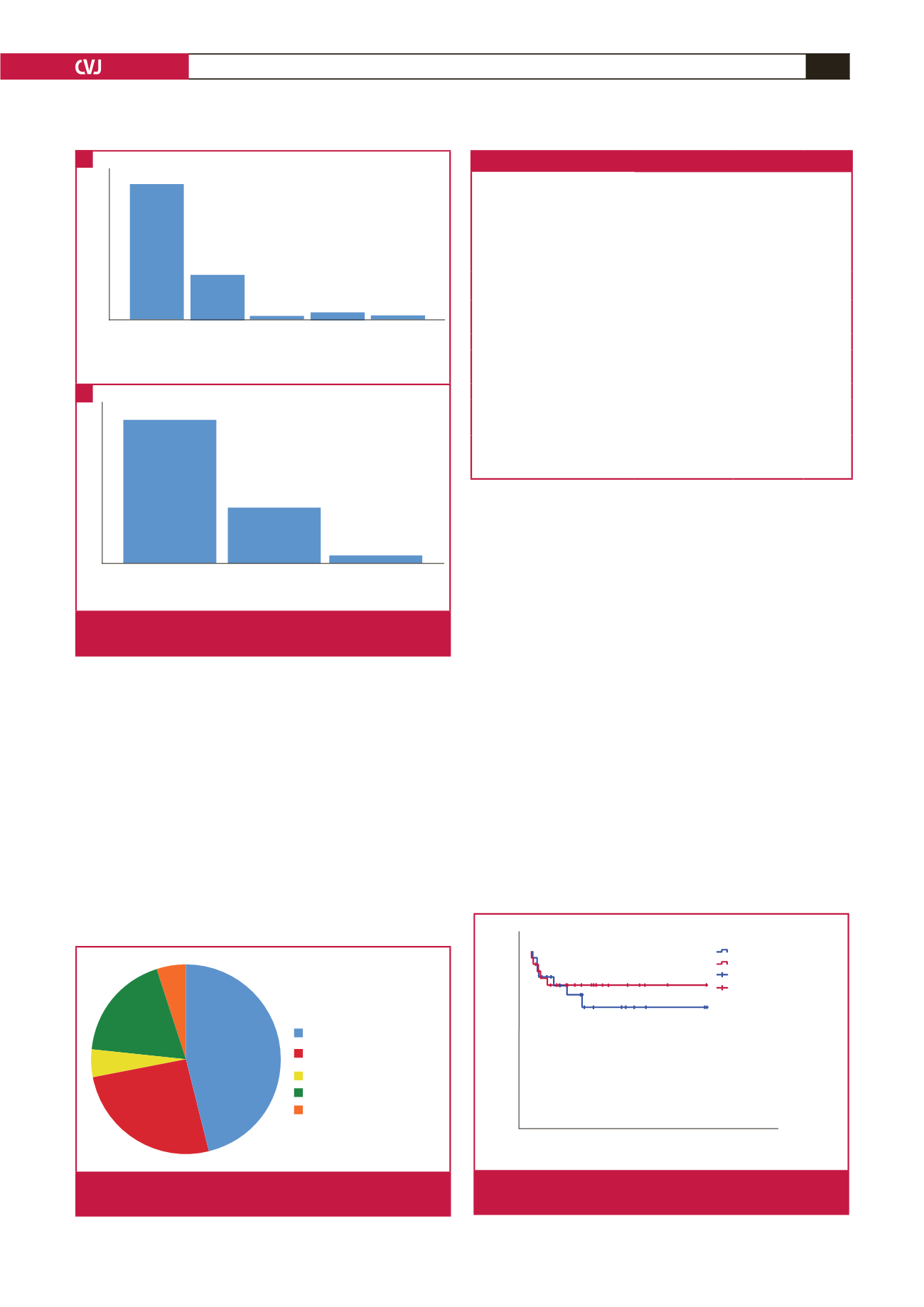

a snare. The overall one-year mortality rate after lead removal

was 19.1% (19.2% in the extraction group vs 14.8% in the

explant group) (

p

= 0.764). There was no difference in survival

rate between patients who had their CIEDs extracted versus

explanted (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The key findings of this study are: (1) CIED-related infection

was the leading indication for CIED removal (extraction or

and explant) at a tertiary referral centre in South Africa; (2)

percutaneous tranvenous lead extraction using a locking stylet

with or without mechanical extraction sheaths had a high

procedural and clinical success rate; (3) percutaneous lead

removal was associated with a low risk of major and minor

complications and low mortality rate, which is comparable with

high-volume centres in Europe and North America; and (4)

the overall one-year mortality rate remained high, similar to

previous reports.

The implantation rates of CIEDs are increasing globally and

in low- to middle-income countries such as South Africa.

9,10,18

The

rates of CIED removal, particularly for CIED infection, have

also been on the rise.

8,12

The findings of this study are consistent

with the current international standard of extraction procedural

success rate of more than 80%, clinical success rate of more than

95% and major complication rate of less than 5%.

11,13

Although patients who underwent lead extraction in this

study had a low in-hospital mortality rate of 3.8%, we found

that the one-year mortality rate was 19.2%. These findings are

consistent with a study by Maytin

et al

., who reported a 30-day

mortality rate of 2.1%, one-year mortality rate of 8.4% and

a 10-year mortality rate of 46.8% in patients who had their

leads extracted.

19

Therefore, although the in-hospital mortality

rate and minor and major complication rates related to lead

Table 2. Lead-removal procedure details and outcomes

Variables

Removal (extraction

and explant)

(

n

= 53)

Extraction

(

n

= 26)

Explant

(

n

= 27)

Days since primary implantation,

median (IQR)

243 (53–831)

831

(359.5–2546)

57

(36–104)

Total number of removed leads,

mean (SD)

75

40

35

Number of removed leads per

patient

1.42 (0.69)

1.54 (0.76) 1.3 (0.61)

Locking stylet,

n

(%)

24 (45.3)

24 (92.3)

0

Extraction sheath,

n

(%)

19 (35.8)

19 (73.1)

0

Straight stylet,

n

(%)

27 (50.9)

26 (100)

25 (92.6)

Procedural success,

n

(%)

49 (92.5)

22 (84.6)

27 (100)

Clinical success,

n

(%)

53 (100)

25 (96.2)

27 (100)

Major complications,

n

(%)*

1 (1.9)

1 (3.8)

0

Minor complications,

n

(%)

#

1 (1.9)

1 (3.8)

0

In-hospital mortality,

n

(%)

1 (1.9)

1 (3.8)

0

*There was one death, which was recorded as a major complication.

#

One minor complication was a lead-fragment embolism to the lung without

complications.

Culture

Culture negative

Methicillin-susceptible

staphylococci

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Staphyhylococcus epidermis

Escherichia coli

2.70%

48.65%

18.92%

27.03%

2.70%

Fig. 2.

Pie chart depicting the frequency of causative micro-

organisms for CIED infection leading to CIED removal.

Infection Lead

malfunction

Lead

dislodgement

Arrythmia RV

perforation

Indication for removal

Percentage

20

40

60

0

Percentage

0

20

40

60

Infection

Lead malfunction Lead dislodgement

Indication for extraction

Fig. 1.

A. Bar chart depicting indications for CIED removal.

B. Bar chart depicting indications for CIED extraction.

A

B

Follow up in days

Log rank = 0.287

Culumative survival

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

Explant

Extration – censored

Explant – censored

Extraction

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves depicting the cumulative survival

difference between the extraction and explant group.