CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 22, No 3, May/June 2011

142

AFRICA

physical examination was unremarkable.

The basic laboratory parameters were within normal limits.

MRI of his head and his EEG revealed no abnormalities. The

only significant finding was his ECG, which showed a Wolff–

Parkinson–White (WPW) pattern (Fig. 1). He had no record of

previous ECG. With this negative work up and normal neuro-

logical examination, the seizure episode was attributed to WPW

syndrome, leading to tachyarrhythmia and a transient haemo-

dynamic instability, which in turn would have caused cerebral

hypoxia leading to seizure.

Further work up included a stress test and two-dimensional

echocardiogram, both of which turned out to be normal. He

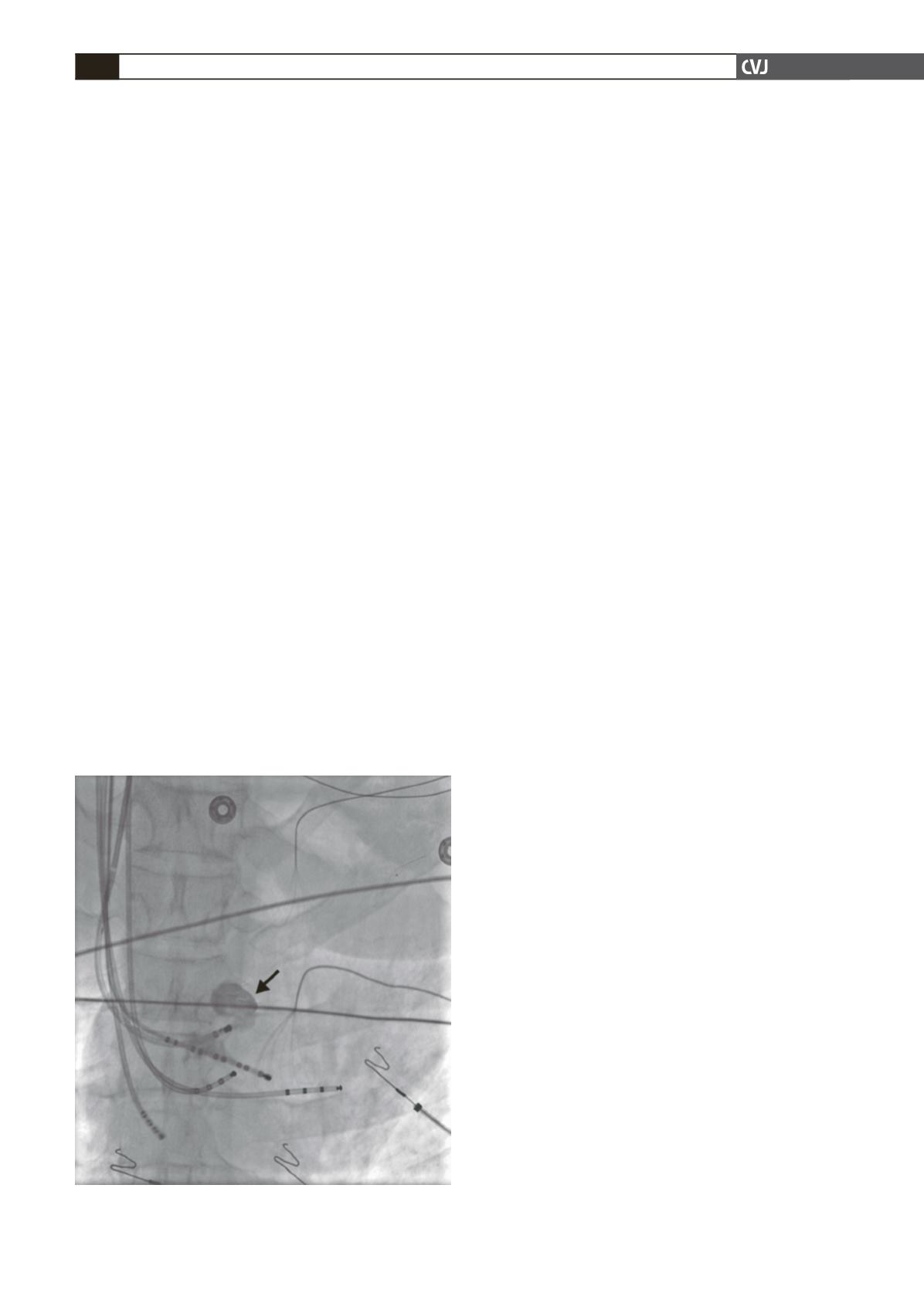

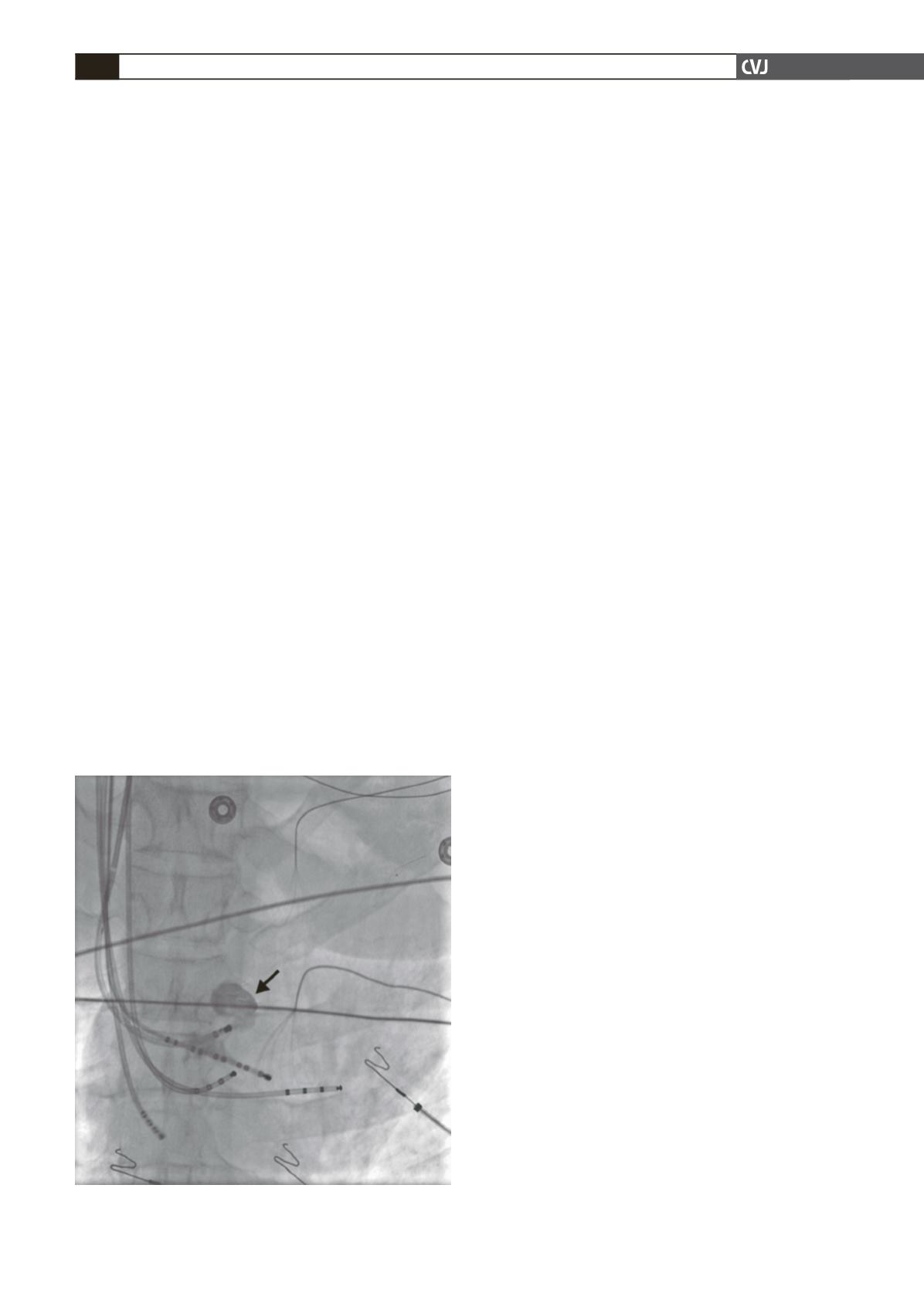

was taken for cardiac catheterisation and electrophysiological

study (EPS), which revealed coronary sinus aneurysm (Fig. 2)

and an accessory pathway within the coronary sinus aneurysm.

Arrhythmogenicity was confirmed by inducible ventricular

fibrillation during EPS. Coronary sinus aneurysm was further

confirmed by CT angiogram.

Ablation of the aneurysm was warranted but the inaccessible

location within the coronary sinus proved to be a challenge.

Later, a probe was custom made for this purpose and the acces-

sory pathway was successfully ablated.

Discussion

Abnormalities in the coronary sinus are unusual and they may

coexist with accessory pathways. Their real incidence is not

known. In a recent report by Morgan

et al

.,

4

4% of 300 patients

with cardiac rhythm anomalies had a coexistent anomalous

coronary sinus.

In 1988, Robinson

et al

.

5

reported a patient with WPW and

a coronary sinus anomaly, which was detected in necropsy. In

another report, in a series of 53 WPW patients, the incidence of

coronary sinus anomaly was found to be 13%.

6

Tebbenjohanns

et al

.

7

have conducted direct coronary sinus angiography in 43

patients with posteroseptal accessory pathways. They showed

that venous branch or coronary sinus anomalies were associ-

ated with the majority of patients with a posteroseptal accessory

pathway.

In our case, the patient had WPW syndrome. We attempted

ablation of the accessory pathway but were unsuccessful. He

later underwent electrode catheter ablation through a coronary

sinus branch.

The majority of free-wall accessory pathways are located in

the epicardial fat pad. Catheter ablation requires precise locali-

sation of the accessory pathway and delivers energy to that area

only. Occasionally but unusually, inferoseptal or left posterolat-

eral accessory pathways cannot be successfully ablated with the

use of an endocardial catheter, and energy needs to be delivered

within the coronary sinus or one of its branches. For left postero-

lateral accessory pathways that cannot be ablated from the endo-

cardium, a mid to distal coronary sinus location may be used.

8

The surface ECG may also provide some clues regarding

the location of the accessory pathway. The presence of a nega-

tive delta wave in lead II may correspond to the presence of an

inferoseptal accessory pathway located within the middle cardiac

venous system. Additionally, the presence of an initial R wave in

lead V1 may suggest the presence of a left inferoseptal accessory

pathway.

Attempts at accessory pathway ablation through the coronary

sinus using radio-frequency energy are associated with a success

rate in excess of 70%.

9,10

A major deterrent to accessory pathway

ablation within the coronary sinus or its branches may be the

greater potential for complications, compared with endocardial

ablation. Until recently, the most serious complications encoun-

tered were coronary sinus perforation with cardiac tamponade,

pericarditis and asymptomatic coronary sinus thrombosis.

10,11

Unfortunately, as this procedure has been performed quite

frequently, cases have been reported in which both clinically

significant and non-significant occlusions of the coronary arter-

ies (predominantly branches of the right coronary artery) adja-

cent to coronary venous branches have occurred.

11

It is therefore

very important that this procedure be performed with proper

surgical backup.

These anomalies alone are usually asymptomatic, although

they may complicate the mapping of the coronary sinus and

catheter ablation when associated with accessory pathways. As a

result, anomalies of the coronary sinus, as in this case, may be asso-

ciated with abnormalities of the conduction system of the heart.

Whether the combination of these types of anatomical anomalies

is a coincidence or whether there is an embryological link between

the accessory pathway and the coronary vein is not known.

Conclusion

Radio-frequency catheter ablation of an accessory pathway in the

coronary sinus can be effectively performed through the proxi-

mal portion of the middle cardiac vein. In view of more recent

reports of adverse sequelae, however, zealous performance of

such procedures should await the development and documenta-

tion of safer methodologies. In certain situations, referral for

surgical interruption of the accessory pathway may not be neces-

sary if the accessory pathway cannot be ablated from a more

conventional tricuspid or mitral annular location. In fact, in

the case described here, catheter ablation was successful where

previous ablations had failed.

Fig. 2. Coronary sinus aneurysm (arrow) on coronary

angiogram.