CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 22, No 3, May/June 2011

144

AFRICA

the ascending aorta. Therefore traumatic pseudoaneurysm asso-

ciated with insertion of the tube was excluded (Fig. 2). It was

thought that the pseudoaneurysm was associated with contami-

nation with purulent bacterial effusion. Because of the risk of

spontaneous rupture, emergency surgery was performed via a

sternotomy using cardiopulmonary bypass.

The mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the ascending aorta arose

from the postero-lateral wall of the aorta above the sinotubular

junction. The aortic wall defect left by the neck of the pseu-

doaneurysm was about 3

×

4 cm after excision of the pseodo-

aneurysm. The defect margins were reached between the non-

coronary and left coronary cuspis commissures. The aortic wall

defect was closed with a pericardial patch, with the use of 4/0

polypropylene sutures together with non-coronary commissural

resuspention stitch.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery. MSCT

was repeated postoperatively and showed no pathology relating

to the ascending aorta and no pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 1D).

Conclusion

We reported on a child with a normal cardiac history who had

developed a mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the ascending aorta due

to purulent bacterial pericardial effusion in the absence of aortic

surgery or blunt trauma.

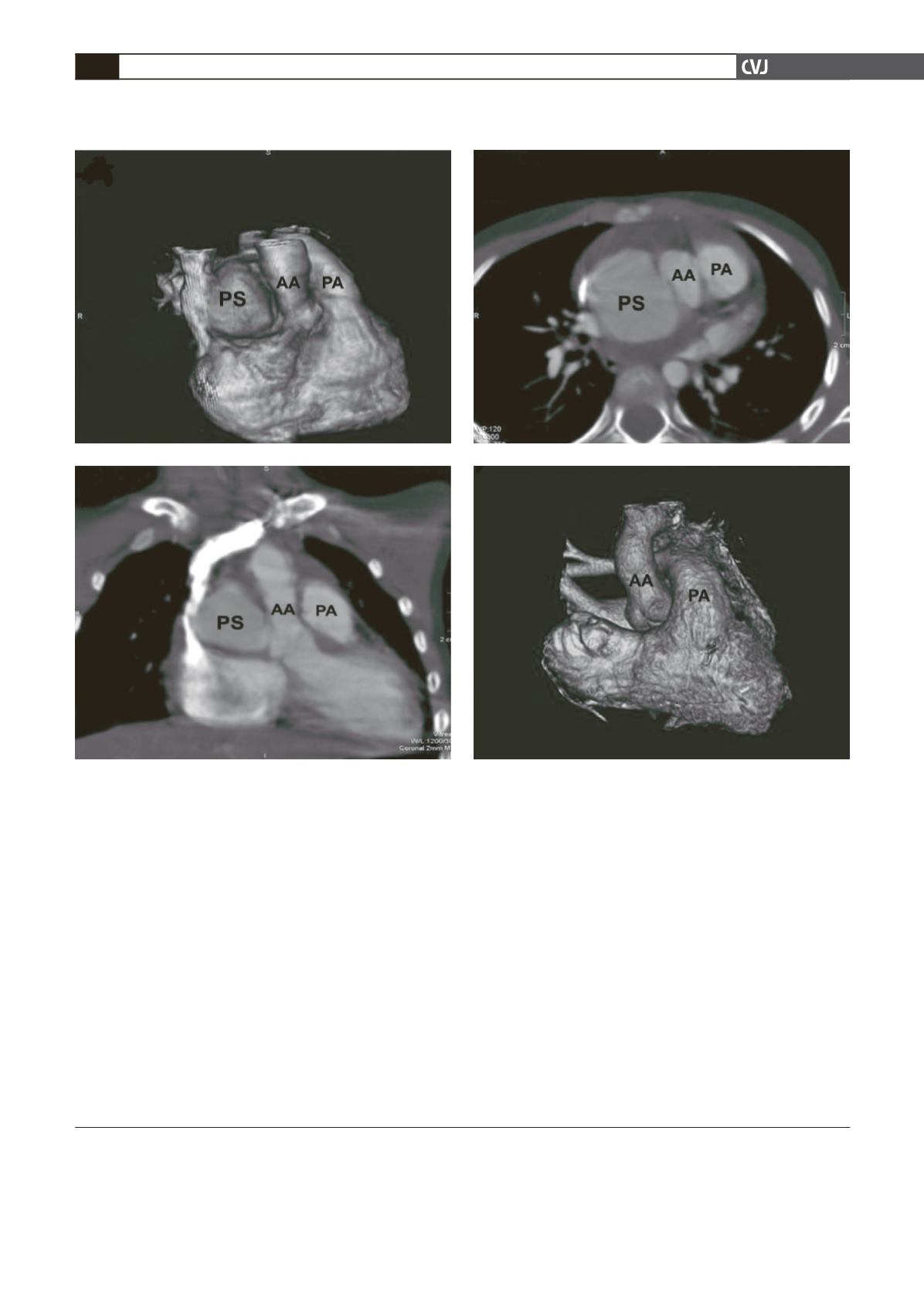

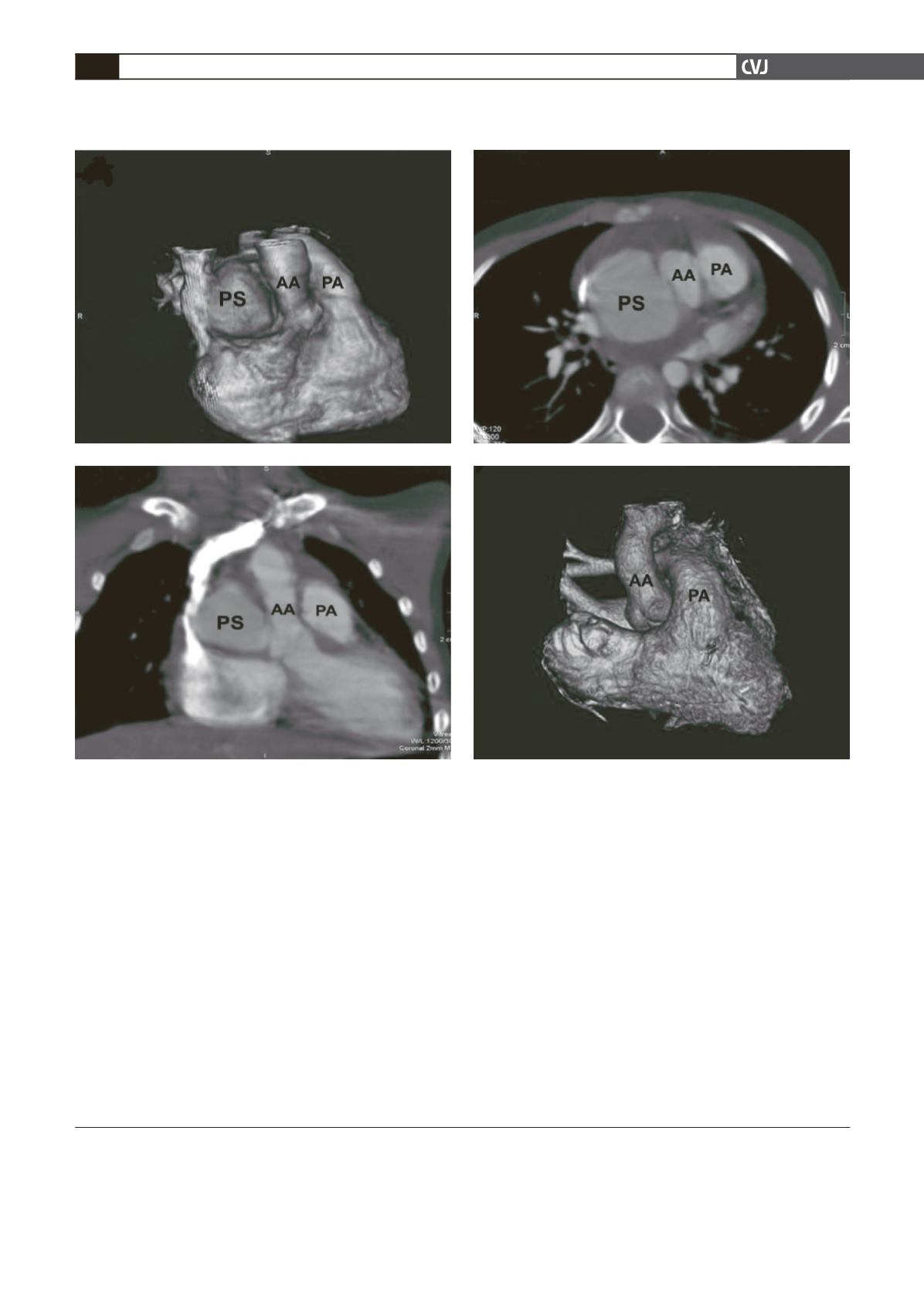

Fig. 1A–C: Multi-slice computed tomography showing a 4 × 5-cm mass between the superior vena cava and ascending

aorta, which was diagnosed as a pseudoaneurysm. D: Postoperatively, multi-slice computed tomography showed no

pathology relating to the ascending aorta and no pseudoaneurysm.

C

D

A

B