CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 2, March/April 2015

AFRICA

99

tachyarrhythmias or conduction abnormalities accounts for

25–65% of cardiac sarcoidosis-related deaths.

8

Complicated

sarcoidosis has been associated with postpartum maternal

death.

9

Our two patients delivered by caesarean section and had

no further complications.

Diagnostic tools

There are no currently accepted international guidelines for

the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. The diagnosis of cardiac

sarcoidosis can be difficult, as it can be asymptomatic or

non-specific. Cardiac sarcoidosis is manifested clinically

as a cardiomyopathy with loss of ventricular function, or

tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias (palpitations, syncope

and sudden death).

Both our patients presented with atrial arrhythmias. The first

patient (case 1) had atrial fibrillation (more frequent and faster

heart rate than before pregnancy) and the second patient (case

2) had supraventricular tachycardia. The most common location

for granulomas and scars is the left ventricular free wall, followed

by the interventricular septum, often with involvement of the

conducting system.

Endomyocardial biopsy sample for pathological research

that is positive is hard to obtain and has a low diagnostic yield

(

<

20%) because cardiac involvement tends to be patchy, and

granulomas are more likely to be located in the left ventricle and

basal part of the ventricular septum.

10

A pathological diagnosis

of cardiac sarcoidosis was not performed in our two patients

for these reasons. Instead, we chose to perform a less-invasive

cardiac MRI. Cardiac MRI with gadolinium enhancement and

a

18

F-FDG PET scan are valuable aids in the diagnosis of cardiac

sarcoidosis.

3

Since sudden death may be the first sign of cardiac

sarcoidosis, electrophysiological studies to detect any conduction

delays or increased risk of sustained arrhythmias should be

strongly considered in all patients with suspected cardiac

sarcoidosis. Most authorities recommend placement of an

electronic pacemaker for complete heart block, and an automatic

implantable cardioverter–defibrillator for ventricular fibrillation

or tachycardia and markedly reduced left ventricular ejection

fraction.

11

Sarcoidal granulomas produce angiotensin converting

enzyme (ACE), and ACE levels are elevated in 60% of patients

with sarcoidosis. However, a serum ACE level is an insensitive

and non-specific diagnostic test and a poor therapeutic guide.

3

A recently published expert consensus statement provides

guidance for clinicians on the diagnosis and management of

arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis.

12

Unfortunately

they do not have

recommendations for pregnant patients as there

is limited evidence for this specific patient population.

Treatment

The initial treatment of sarcoidosis is often prednisone 20–40

mg daily for six to 12 weeks, with dose reduction thereafter. As

cardiac sarcoidosis is a potentially life-threatening situation, the

initial dose is 1 mg/kg daily. Although a minimum of 12 months

of maintenance therapy is often advised to prevent relapse,

several investigators believe that treatment should be stopped as

early as six months after initiation.

13

Oral steroid therapy is usually performed to treat

atrioventricular block due to cardiac sarcoidosis. However, its

efficacy against cardiac sarcoidosis in general is only about

50%.

14,15

Although cardiac sarcoidosis is a known inflammatory

disease anddespitemore than50 years of the use of corticosteroids

for treatment, there is no proof of survival benefit from this

treatment.

16

As specific guidelines on cardiac sarcoidosis in pregnant

women do not exist, in case of occurring relevant bradycardia

or tachycardia, pacemakers and ICDs may be considered

.

Since

there is no evidence of giving immunosuppressive therapy for

pregnant women, we suggest that efforts should be made to

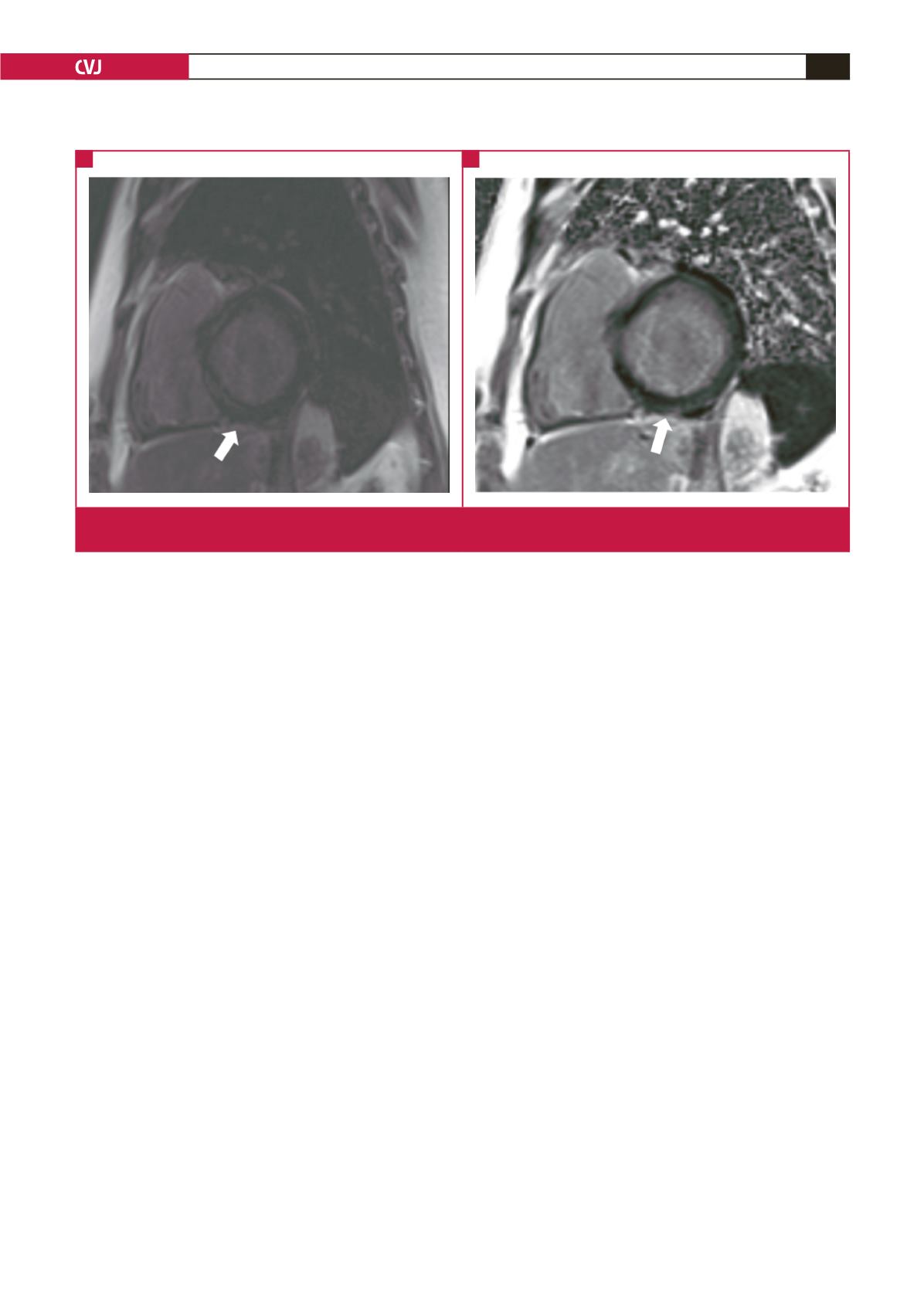

Fig. 3.

Cardiac MRI images of case 2. Basal short-axis left ventricular magnitude (A), and PSIR (B) delayed enhancement images,

demonstrating mesocardial (white arrow in A) and epicardial enhancement (white arrow in B).

A

B