CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 2, March/April 2015

94

AFRICA

counselling, as this case report has shown. An experienced

physician would have avoided the long in-hospital stay that this

patient had without any specific management. Refusing to be

discharged without medical indications is a manifestation of the

patient’s altered cognitive function, which had significant cost

implications. Indeed, ‘paying for care’ in low-resource settings

has great financial implications.

The life-threatening conditions of the patients in three reported

cases would have impacted negatively on their QoL. This would

have been a source of significant stress to the family.

9,10

Lessons from the guidelines

The most common electrical mechanism of cardiac arrest

is ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia,

but substantial numbers of cases of cardiac arrest begin as

severe bradyarrhythmias, asystole or ventricular tachycardia.

The guidelines

6,11

state the following:

•

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be implemented after

contacting a response team (class I, level of evidence A).

•

For victims of ventricular tachyarrhythmic mechanisms of

cardiac arrest who have recurrences after maximal defibril-

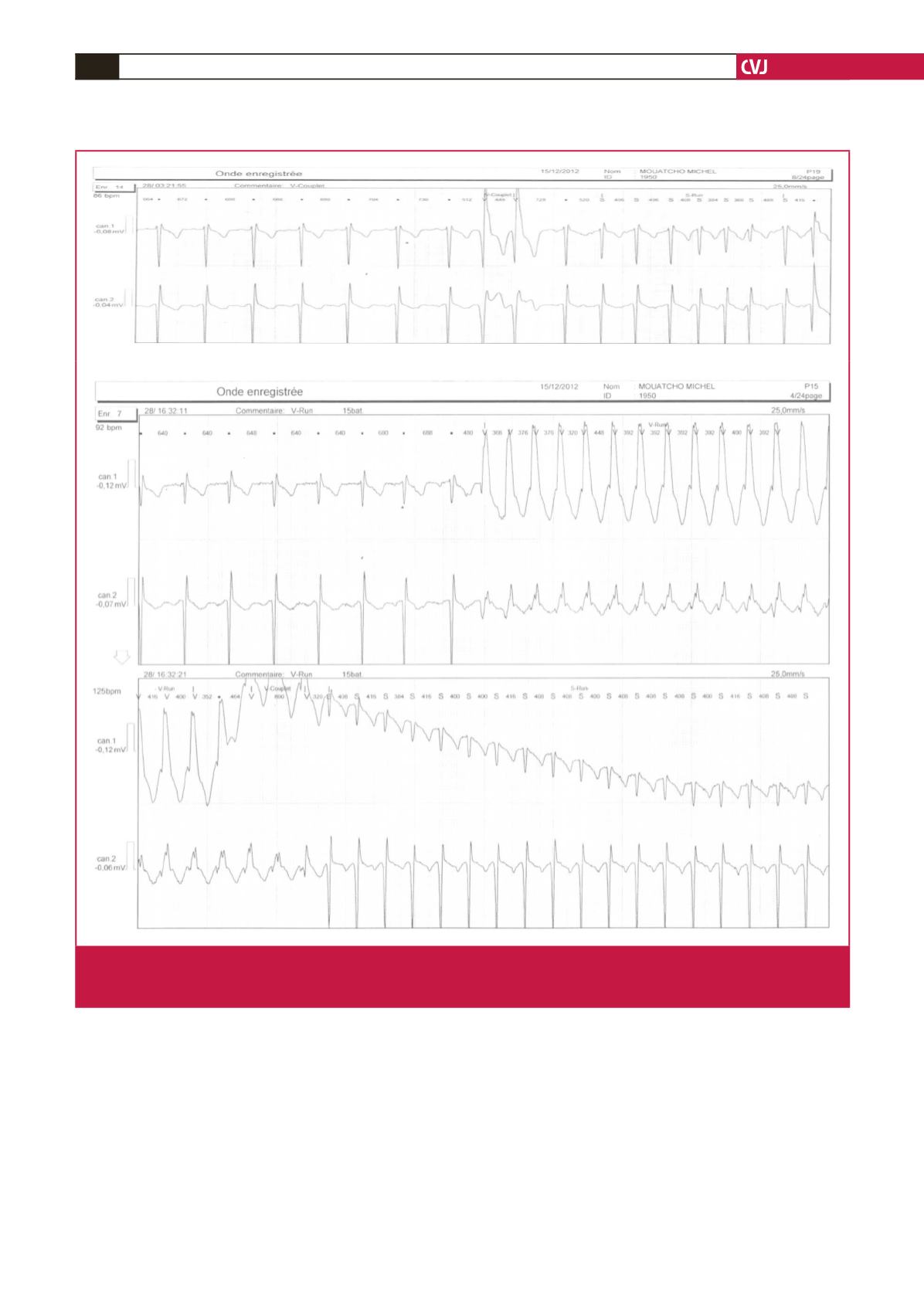

Fig. 3.

ECG recordings showing premature ventricular contractions a few days after the patient had experienced SCA. Top: two-lead

recording showing paired premature ventricular contractions. Bottom: one-lead recording registered sustained ventricular

tachycardia, which was amended by external electrical cardioversion.