CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 26, No 3, May/June 2015

AFRICA

e13

three times on the same day because of increased ischaemic

changes. The thrombectomy was not successful.

We suspected type 2 HIT. Heparin therapy was immediately

discontinued on postoperative day three, including all intravenous

fluids and lines. On the basis of the clinical symptoms, we used the

‘4 Ts’ clinical scoring system to test for the possibility of HIT, and

found a high probability of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

A laboratory test was performed on postoperative day six,

and a definitive diagnosis of HIT was made by serological test,

confirming positive antibodies to the heparin–PF4 complexes

with a slow turnaround time. Complete thrombophilic studies

were unremarkable for other hypercoagulable conditions.

Anticoagulation was immediately started with fondaparinux,

which is the only alternative anticoagulant agent in our country,

at the recommended dose for these patients (7.5 mg/day,

subcutaneous) on postoperative day four because of a fall in

platelet count of more than 50%. The patient’s platelet count had

not increased during therapy with fondaparinux after seven days.

The patient developed acute renal insufficiency requiring

haemodialysis on postoperative day nine. Fondaparinux (2.5 mg)

was also instilled directly into the dialysis circuit on dialysis days.

On the 11th day postoperatively, the patient died of multiple

organ failure despite intensive care.

Discussion

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is routinely used worldwide

during CPB procedures and other various conditions for systemic

anticoagulation.

4

However, a small percentage of patients treated

with UFH or low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) suffer

complications caused by side effects of the drug, the most serious

of which is HIT.

1

HIT is an adverse effect of the drug causing

potentially fatal thrombotic or thromboembolic complications.

HIT is a clinicopathological condition initiated with heparin

exposure and characterised by a fall in the platelet count and

paradoxical thrombophilia.

5,6

HIT syndrome may be classified into two distinct subtypes

based on differences in the pathophysiology and clinical features:

type 1 and type 2. Type 1 HIT is non-immune and typically

occurs as a fall in platelet count within the first two days after

starting heparin. Platelet levels generally decrease by 10–20%.

7

This condition usually resolves spontaneously without treatment

or complications within days, even with continued heparin use.

It is a non-immune-mediated disorder and appears to be due to

a direct activation of the platelets by heparin, leading to platelet

aggregation and, as a result, thrombocytopenia.

By contrast, the less common and more severe form, type

2 HIT is an immune-mediated disorder caused by antibody

formation against the circulating H-PF4 complexes. This type can

be associated with thrombotic or thromboembolic complications.

It is also known as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and

thrombosis (HITT) and white clot syndrome due to platelet-rich

arterial thrombosis.

5

In most cases, thrombocytopenia develops

on approximately the fifth day of initiation of heparin.

8

The incidence of type 2 HIT is significantly higher after

exposure to UFH versus LMWH (2.6 vs 0.2%).

9

Surgical patients

(especially cardiac surgery) are also more likely to develop HIT

than medical patients.

5

The incidence of HITT in patients who have undergone

cardiac surgery has been estimated at between 0.12 and 1.3%.

10

Cardiac surgical patients are at a greater risk for postoperative

HITT due to several factors. First, most of these patients have

had previous exposure to heparin for diagnostic, prophylactic

and therapeutic purposes. Second, they are exposed to high-dose

intra-operative heparin during CPB, and platelet activation is

associated with surgery and CPB. Third, this exposure is usually

continued in the postoperative period (either prophylactically or

for flushing the lines).

11

The common clinical presentation of HIT involves

thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. Thrombocytopenia is the

primary manifestation of HIT, but the degree and onset of

the fall in platelet count may be variable. Type 1 HIT is often

characterised by a fall in platelet count within one and four days

after heparin exposure, with a nadir level of 100 000 cells/

μ

l,

spontaneous normalisation despite continued heparin use, and

no other clinical sequelae.

On the other hand, type 2 HIT occurs within five to 10 days

after the administration of heparin. The platelet counts fall

more significantly by

≥

50% or

≥

100 000 cells/

μ

l, with a median

nadir of ~ 60 000 cells/

μ

l.

7

However, even when platelet counts

in type 2 HIT are typically

<

20 000/

μ

l, spontaneous bleeding is

uncommon. Thrombosis is the main contributor to morbidity

and mortality associated with type 2 HIT, and HIT is fatal in

an estimated 5–10% of patients, typically due to thrombotic or

thromboembolic events.

Thrombosis may accompany thrombocytopenia in 30–60%

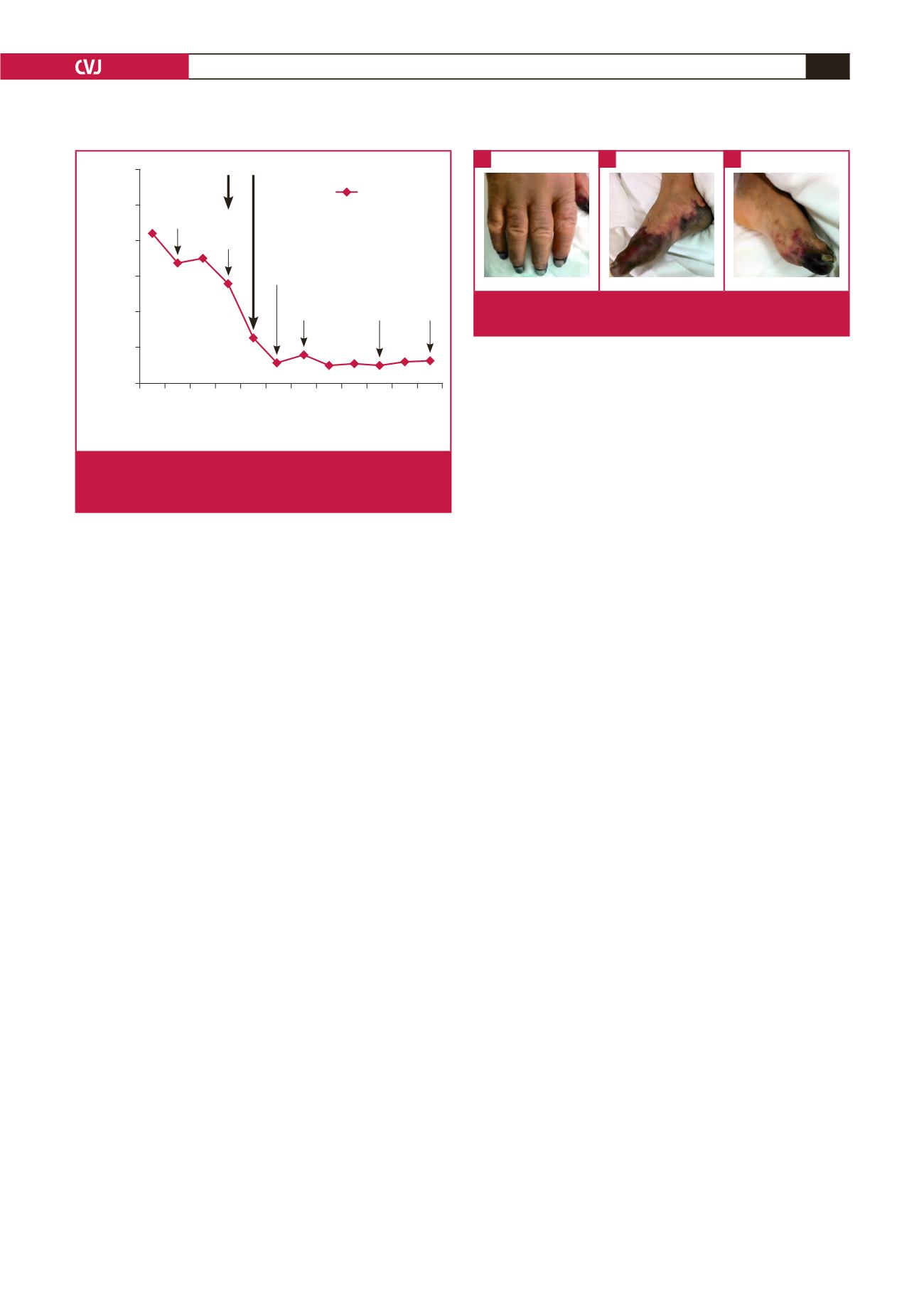

Fig. 3.

The ischaemic changes in the right hand (A), right foot

(B), and left food (C).

A

B

C

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

Pre-

op

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Hospital day

Platelet count (x 1 000)

Platelet count

26 500 U

heparin

in OR

Died

ARF and

haemodialysis

Both food

ischaemia

Fondaparinux was started

Heparin was stopped

Weaning

time from

the IABP

Right-hand ischaemia

and brachial

thrombectomy

Fig. 2.

Platelet counts and key clinical events during hospi-

talisation. ARF: acute renal failure, IABP: intra-aortic balloon

pump, OR: operating room.