CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

226

AFRICA

National Hospital, a major public referral centre, to evaluate the

presentation, management and outcomes of patients with ACS.

Methods

FromNovember 2016 to April 2017 we conducted a retrospective

chart review of ACS cases managed at Kenyatta National

Hospital from 2013 to 2016. We used the existing electronic

disease code database to identify ACS cases, using primary

discharge codes (I20-I24) from the World Health Organisation

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) system.

5

The diagnosis of ACS subtype was made by the primary

treating physician at the time of the index hospitalisation, based

on the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.

6

We excluded cases that had a primary diagnosis of ACS, but

upon further review of the medical admission, most likely had

myocardial infarction secondary to a non-ACS aetiology (i.e. a

non-type 1 myocardial infarction). In cases that the ACS subtype

was not directly specified in the medical record, the primary data

extractor (EB) reviewed each clinical presentation, biomarkers

and ECG findings and determined the ACS subtype based on

the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.

6

We included adults over 18 years with a diagnosis of ACS

admitted and managed between 2013 and 2016. We abstracted

demographics, presentation, self-reported medical history,

diagnostics, treatment data and in-hospital clinical events. We

used combined paper and electronic data-capture systems to

abstract data from the medical record, which was performed by

one author (EB).

We defined guideline-directed in-hospital medical therapy as

receiving a combination of aspirin, a second antiplatelet (e.g.

clopidogrel, ticagrelor or prasugrel), beta-blocker within 24

hours of presentation and anticoagulation at any point during

the hospitalisation. We defined guideline-directed discharge

medical therapy as receiving a combination of aspirin, second

antiplatelet drug, beta-blocker and statin. We assessed in-hospital

outcomes, including in-hospital death and in-hospital major

adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the composite

of in-hospital death, re-infarction, stroke, heart failure, major

bleeding or cardiac arrest.

We acquired ethics approval to conduct this research from

the Kenyatta National Hospital and University of Nairobi

ethics research committee (KNH-UON ERC), Northwestern

University institutional review board, and University of

Washington institutional review board. Informed consent was

waived based on the retrospective nature of the study for the

collection of anonymised data.

Statistical analysis

We present continuous data as means (standard deviation)

or median (range or interquartile range) when skewed, and

categorical data as proportions. Comparisons by ACS subtype

were made via analysis of variance for continuous variables

and chi-squared testing for categorical variables. We created

multivariable logistic regression models using the Global Registry

of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score to evaluate

the association between clinical variables, including guideline-

directed medical therapy and in-hospital death or major adverse

cardiovascular events.

4

We defined statistical significance using a

two-sided

p

-value

<

0.05. We used Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp,

LLC. College Station, TX).

5

Results

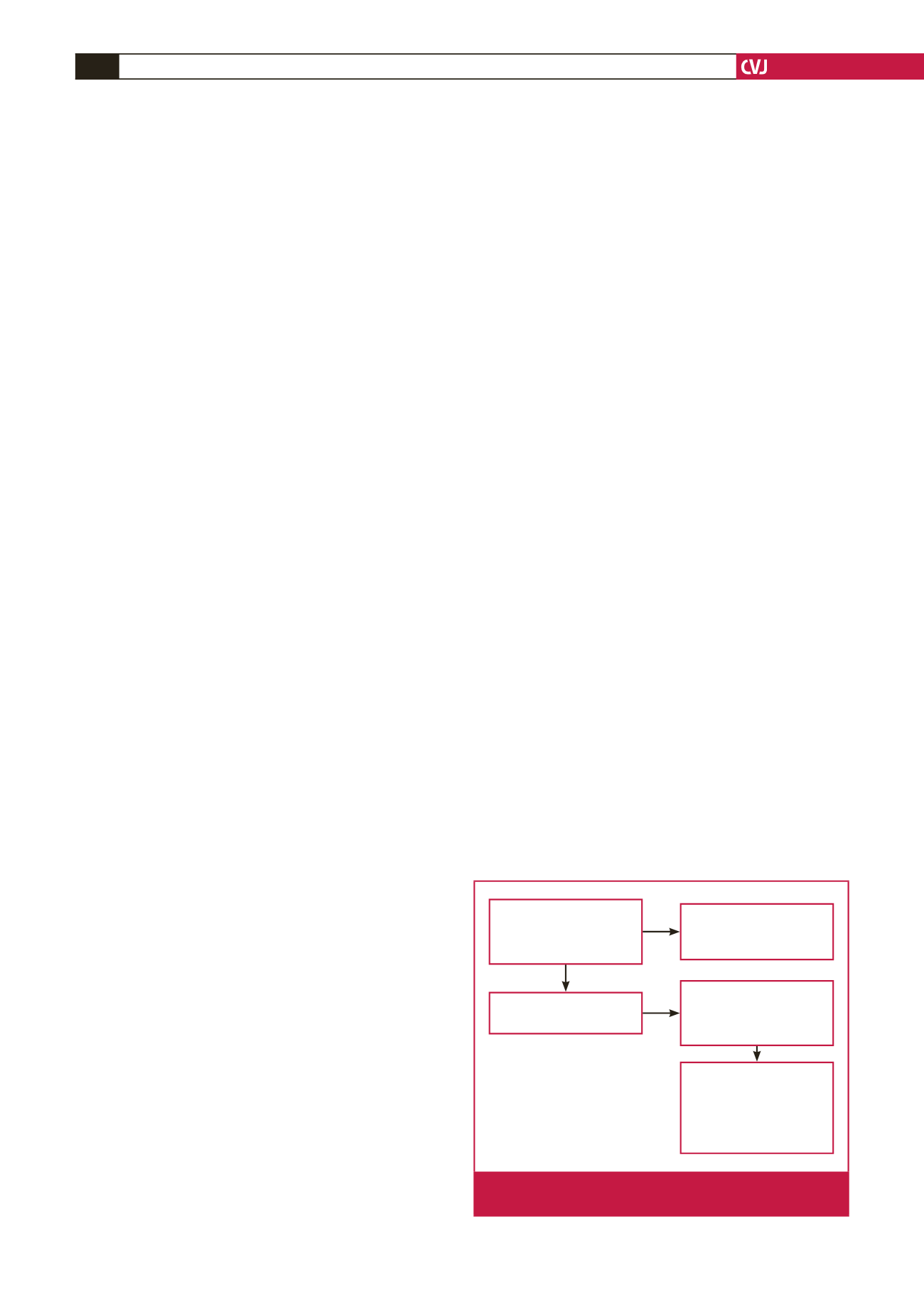

Fig. 1 demonstrates the flow of participants in this study. We

identified a total of 330 admissions that met our study criteria.

We could only retrieve partial admission data from 2013 due to

a hospital-wide electronic database loss that occurred between

2011 and 2013, which led to the exclusion of 51 cases. A further

81 cases were excluded because of incorrect diagnosis (20)

or ACS not being the primary discharge diagnosis (61). We

therefore included 196 cases in our final analysis.

Table 1 summarises patients’ baseline characteristics by ACS

subtype. The majority (57%) of the cases were ST-elevation

myocardial infarction (STEMI) followed by non-ST-elevation

myocardial infarction (NSTEMI, 26%) and unstable angina

(UA, 12%). Cases without an ECG but with positive biomarkers

and clinical presentation consistent with ACS represented 5% of

cases. Most participants (64%) were men, and the median age

(IQR) was 58 (48–68) years. More than one-third (38%) of all

admissions were transferred from an outside hospital.

Hypertension (63%) was the most common co-morbidity,

followed by diabetes (41%). Smoking rates were low across all

groups (9%); however, 27% had undocumented smoking status,

which likely led to underestimation of the overall smoking

prevalence. The proportion of patients who presented in heart

failure with Killip class

>

1 was highest among STEMI cases

(44%).

Table 2 shows a summary of the in-hospital management

of ACS patients. We stratified the data into four groups: key

investigations, in-hospital acute medical therapy focusing on

administration of guideline-directed medications within the

first 24 hours of admission, in-hospital reperfusion therapy, and

discharge medical therapy.

Overall, 82% of all cases received an ECG within 24 hours

of presentation, with higher rates among patients who were

transferred versus non-transfer patients (88 vs 71%,

p

<

0.001).

The proportion of patients that received an ECG within 24

hours of admission each year between 2013 and 2016 was 82,

51 charts not available

due to hospital-wide

electronic database loss

330 cases identified

through electronic data-

base search with WHO

ICD-10 code I20-I24

81 cases excluded:

20 wrong diagnoses

61 ACS not the primary

diagnosis

Retrieved charts

for 277 cases

196 cases included in

final analysis

2016: 68 cases

2015: 50 cases

2014: 50 cases

2013: 28 cases

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart of ACS cases admitted to Kenyatta

National Hospital between 2013 and 2016.