CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 29, No 4, July/August 2018

228

AFRICA

antiplatelet, beta-blocker within 24 hours of admission and an

anticoagulant at some point during the hospitalisation was 56%.

Aminority of overall (17 cases, 9%) andSTEMI cases (12 cases,

11%) underwent in-hospital diagnostic cardiac catheterisation

with only 12% undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention

(one NSTEMI, one unstable angina). Using the 2013 American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines

for the management of STEMI,

7

we identified 37 (33%) STEMI

cases eligible for reperfusion, half of whom were transfers. Two

eligible STEMI cases (5%) received thrombolytic therapy and

both were transferred from outside hospitals.

We assessed discharge medical therapy, focusing on guideline-

directed prescription of medications upon discharge and

excluding patients who left against medical advice (

n

=

4).

Discharge aspirin use was 96%, and second antiplatelet agent

discharge use was 82%; combined dual antiplatelet use was

81%. Beta-blocker discharge use was 70%, and statin discharge

use was 86%. The rate of guideline-directed discharge medical

therapy defined as receiving aspirin, a second antiplatelet

and beta-blocker therapy was also 56%. Among individuals

with an ejection fraction less than 40% (

n

=

33), 63% received

an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

Among patients with ejection fraction less than 40%, the rate

of guideline-directed medical therapy with simultaneous dual

antiplatelet, beta-blocker, statin and ACE inhibitor or ARB use

was 48%.

The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 17%, with a

gradient in mortality rate by ACS subtype (STEMI 21%,

NSTEMI 10%, UA 9%, biomarker positive only 30%,

p

=

0.16)

(Table 3). The rate of MACE, defined as death, re-infarction,

stroke, cardiogenic shock, major bleeding or cardiac arrest was

40%, with a similar gradient by ACS subtype (STEMI 54%,

NSTEMI 20%, UA 7%, biomarker positive only 30%,

p

<

0.001)

(Table 3).

Table 4 summarises variables assessed as potential predictors

of in-hospital mortality before and after adjustment using the

GRACE risk score. After multivariable adjustment, higher

serum creatinine level was associated with higher odds of

in-hospital death (OR

=

1.84, 95% CI: 1.21–2.78), and Killip

class

>

1 was associated with in-hospital composite of death,

re-infarction, stroke, major bleeding or cardiac arrest (STEMI:

OR

=

4.71, 95% CI: 2.46–9.02; Killip

>

1: OR

=

10.7, 95% CI:

3.34–34.6).

We also evaluated the association between receiving guideline-

directed in-hospital medical therapy and in-hospital MACE

level using logistic regression and adjusting for covariates in

the GRACE risk score. We did not demonstrate an association

between in-hospital death and combined in-hospital death and

MACE before and after multivariable adjustment (OR

=

0.77,

95% CI: 0.27–2.20; OR

=

1.88, 95% CI: 0.86–4.10, respectively),

but these results were imprecise and were likely driven by the

small sample size and number of events.

Discussion

Through this retrospective chart review we report the

presentation, management and outcomes of ACS patients

managed at Kenyatta National Hospital between 2013 and 2016.

Most patients were men in their late 50s presenting with STEMI.

Approximately one out of every five patients did not receive an

ECG within the first 24 hours, and one out of every 20 patients

did not receive an ECG at all. While more than one out of every

two patients received echocardiography, the gap in ECG care

represents an opportunity for diagnostic improvement. Rates of

in-hospital medical therapy were relatively high but reperfusion

rates among eligible individuals were low. Increasing timely,

appropriate reperfusion therapy for eligible STEMI patients may

be an important area of focus because of the high mortality rate

demonstrated among these patients.

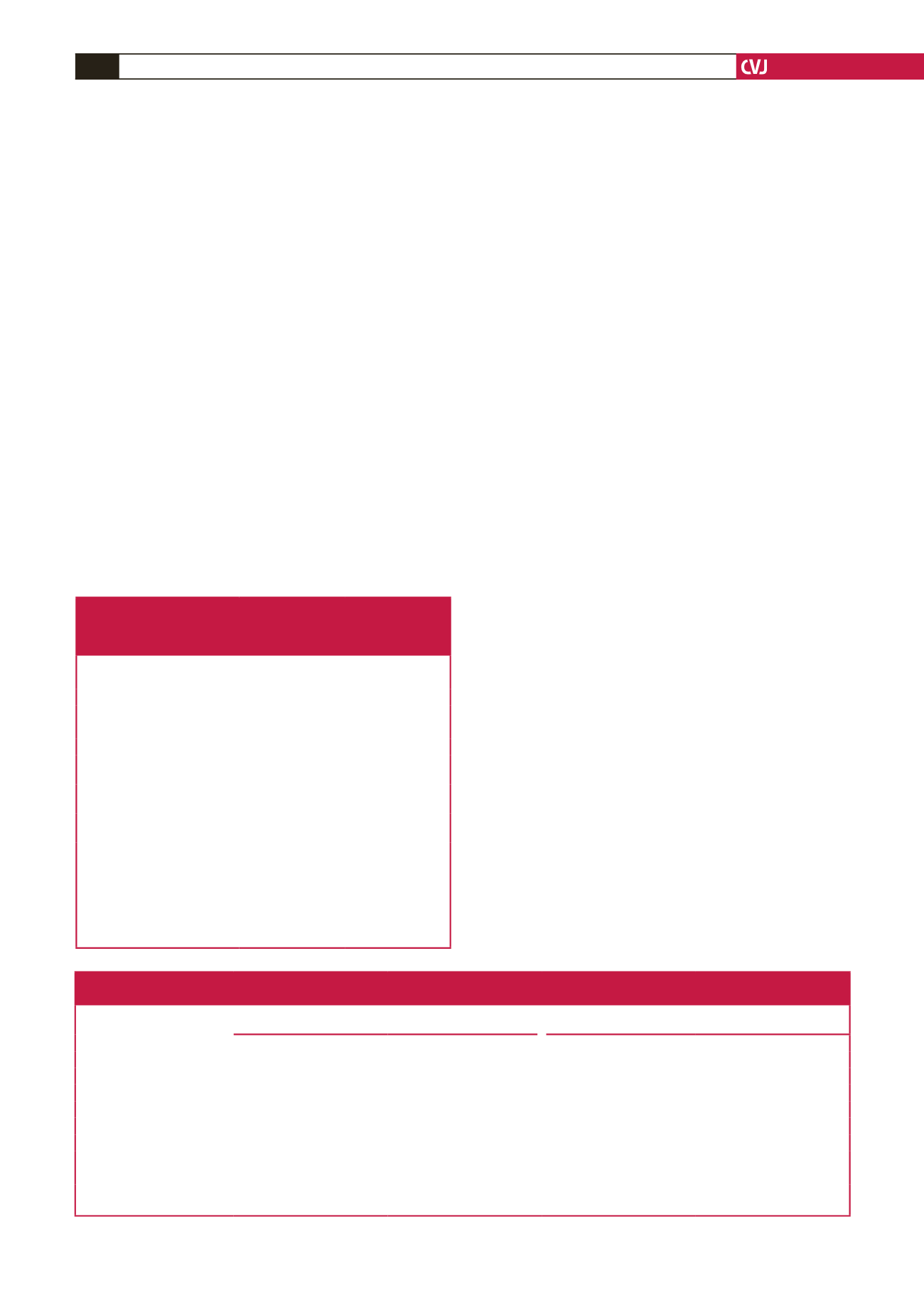

Table 4. Predictors of in-hospital death and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including death, re-infarction, stroke, heart failure,

cardiogenic shock, major bleeding and cardiac arrest of ACS patients admitted to Kenyatta National Hospital between 2013 and 2016

Unadjusted OR (95% CI)

Adjusted (for age, gender and GRACE risk score variables)

OR (95% CI)

Variables

In-hospital death,

n

=

33

In-hospital MACE,

n

=

78

In-hospital death,

n

=

33

In-hospital MACE,

n

=

78

Age (per year)

1.03 (1.0–1.06)*

1.00 (1.01–1.05)*

1.04 (0.98–1.11)

1.01 (0.98–1.06)

Heart rate (per bpm)

0.98 (0.97–1.00)

1.00 (0.99–1.02)

1.02 (0.99–1.11)

1.01 (098–1.04)

SBP (per mmHg)

0.99 (0.98–1.00)

0.99 (0.98–1.00)

0.96 (0.93–0.98)

0.98 (0.96–0.99)

Serum Cr (per mg/dl)

1.35 (1.12–1.66)*

1.13 (0.94–1.34)

1.84 (1.21–2.78)*

1.04 (0.84–1.31)

Killip class 1 vs

>

1

5.80 (2.5–13.7)*

11.45 (0.80–22.4)*

1.8 (0.42–8.14)

10.7 (3.34–34.6)*

Positive cardiac enzyme

2.60 (0.58–11.8)

2.23 (0.89–5.63)

0.91 (0.94–8.80)

1.42 (0.35–5.73)

ST-segment deviation

2.11 (0.85–5.22)

5.35 (2.60–10.99)*

3.12 (0.57–16.87)

1.72 (0.12–24.40)

STEMI vs UA (ref)

2.84 (062–2.98)

8.37 (2.36–29.70)*

0.77(0.02–38.56)

1.71 (0.21–13.80)

*

p

-value

<

0.05; GRACE risk score variables: age, gender, SBP, HR, positive cardiac enzyme, ST-segment change, creatinine, cardiac arrest.

SBP: systolic blood pressure, HR: heart rate, Cr: creatinine, STEMI: ST-segment myocardial infarction.

Table 3. In-hospital mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events

and association between in-hospital guideline-directed therapy and

in-hospital outcomes of ACS patients admitted and managed at

Kenyatta National Hospital between 2013 and 2016

In-hospital mortality In-hospital MACE

All,

n

(%)

33 (17)

78 (40)

STEMI,

n

(%)

23 (21)

61 (54)

NSTEMI,

n

(%)

5 (10)

11 (22)

UA,

n

(%)

2 (8)

3 (13)

BM (+) only

3 (30)

3 (30)

*Guideline-directed in-hospital

medical therapy,

n

(%)

8 (12)

27 (40)

Non-guideline-directed in-hospi-

tal medical therapy,

n

(%)

8 (15)

14 (26)

Guideline-directed vs non-guide-

line-directed, OR (95% CI)

0.76 (0.27–2.20)

1.88 (0.86–4.10)

ACS: acute coronary syndrome, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction,

NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, UA: unstable angina, BM

(+): biomarker positive only: these are cases that presented with symptoms of

ACS and had a positive biomarker test, however did not get an ECG during

their hospitalisation, MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

*Guideline-directed in-hospital medical therapy includes patients who received

aspirin, a second antiplatelet and a beta-blocker within 24 hours of presentation

and an anticoagulant at any point during hospitalisation.