CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 27, No 2, March/April 2016

AFRICA

87

Socio-demographic and health systems issues

In LMICs, delays in enrolment for antenatal care and lack of

adequate healthcare hamper the recognition of life-threatening

conditions and the control of preventable factors that lead

to cardiac decompensation during pregnancy. Low capacity

for diagnosis at peripheral levels of the health systems and

lack of awareness of the risks related to pregnancy result in

few pregnant women being identified as having heart disease,

therefore determining inadequate management and considerable

impact on maternal and foetal outcome. On the other hand,

acute and chronic complications and common endemic diseases

may also further contribute to increase the risk of pregnant

women dying during pregnancy, such as the case with cardiac

tuberculosis, schistomosmiasis and syphilis.

33

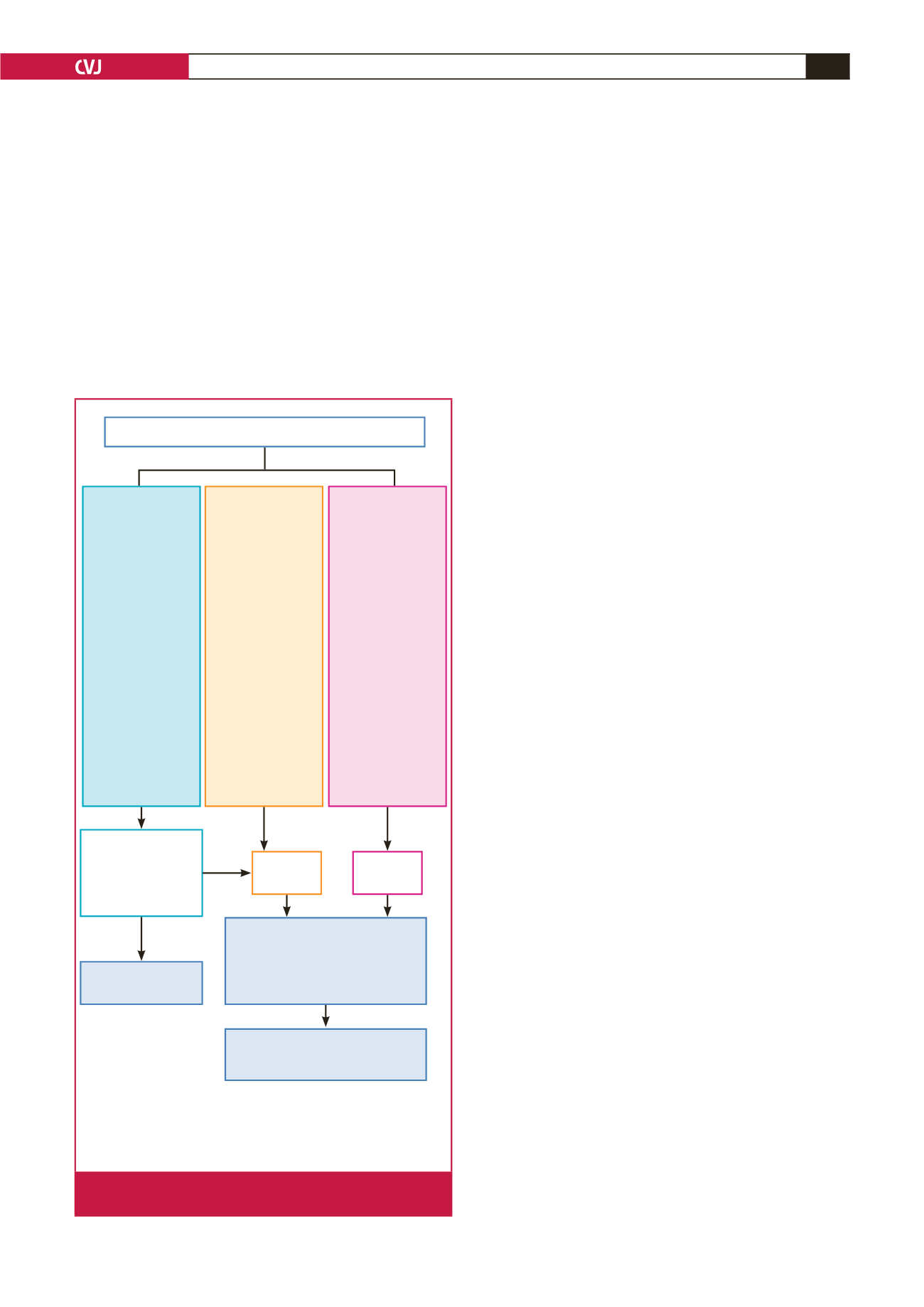

For the identification and management of pregnant patients

with cardiovascular disease, we would therefore recommend

that (1) all pregnant women should be screened at booking

for underlying medical or surgical conditions; (2) women with

known or recently detected cardiovascular disease should

undergo risk assessement based on an algorithm (Fig. 2); (3)

women presenting with difficulty in breathing, systolic blood

pressure of

<

100 mmHg, heart rate

>

120 beats per minute or

appearing cyanotic, need to be transferred by ambulance to a

tertiary centre within 24 hours; those presenting with signs of

fluid overload should receive a bolus of lasix 40 mg IV and

oxygen per face mask prior to transfer; (4) clinicians should have

a low threshold for investigating pregnant or recently delivered

women (up to six months postpartum), especially those with

cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes), suspected

rheumatic heart disease or with symptoms such as shortness of

breath or chest pain; appropriate investigations include ECG,

chest X-ray, echocardiogram and CT pulmonary angiography;

(5) certain patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease may

need careful monitoring for up to one year postpartum due to

the high risk of developing heart failure, serious arrhythmia and

embolic events.

Socio-economic and demographic factors such as persistently

high fertility rates, social pressure to conceive, insufficient access

to contraceptive methods, as well as social or familial ostracism

towards women who use contraception, may further contribute

to increasing the risk of death due to cardiac disease, even in

women who have been diagnosed.

34

Conclusions

Available data on maternal mortality rates reveal the

pre-imminence of cardiovascular disease as the most important

medical cause of non-obstetric maternal death in both developed

and developing countries. Failure to systematically search for

cardiac disease in pregnant women has led to late diagnosis and

high rates of fatal complications. Therefore active screening

for cardiac disease in pregnant women is warranted, if the

millennium development goal of reducing the maternal mortality

ratio is to be achieved.

In LMICs algorithms for cardiac screening of pregnant

women should consider the unique profile of cardiovascular

disease, including rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathies,

HIV/AIDS, haemoglobinopathies and undetected/untreated

congenital heart defects. Such active strategies for suspected

and previously known cardiac disease in pregnancy are expected

to prevent a substantial proportion of maternal morbidity and

mortality.

References

1.

The Millennium Developent Goals Report 2013.United Nations, 2013;

UNDP, UNFPA; UNICEF; UN Women; WHO.

2.

Creanga AA, Berg CJ, KO JY,

et al

. Maternal mortality and morbidity in

the United States: Where are we now?

J Women’s Health

2014;

23

: 3–9.

3.

Nelson-Piercy C. The UK maternal death report.

Obstet Med

2015;

8

: 3.

4.

Nelson-Piercy C. Cardiac disease in Centre for Maternal and Child

Enquiries (CMACE).

Br J Obstet Gynecol

2011;

118

(suppl. 1); 109–115.

Primary and secondary care maternal facility

Modified WHO

classification I

• Previously diag-

nosed hyperten-

sion, diabetes,

morbid obesity

(BMI > 35 kg/m

2

)

• Successfully

repaired simple

lesions

• Uncomplicated,

small or mild mitral

valve prolapse,

pulmonary stenosis

• Palpitations – no

dizziness

Modified WHO

classification

III–IV

• Mechanical valve

and symptoms

• Complex congenital

or cyanotic heart

disease

• Pulmonary hyper-

tension any cause

• Previously diag-

nosed peripartum

cardiomyopathy

• Severe ventricular

impairment (EF <

45%, NYHA FC > II)

• Severe mitral

stenosis and aortic

stenosis

• Aortic dilataion

> 45 mm (bicuspid

AV, Marfan)

Modified WHO

classification II

• Unoperated ASD

and VSD

• Repaired tetralogy

of Fallot and coarc-

tation

• Arrythmias and

dizziness

• Mild left ventricular

impairment (EF >

45%, NYHA FC II)

due to newly diag-

nosed PPCM or HT

heart failure

• Previously diag-

nosed RHD with

murmurs and/or

recently assessed

asymptomatic

mechanical valve

Tertiary care

maternal facility

Tests: BP, ECG,

echocardiogram and

assess for murmurs

Non-urgent

referral

Urgent

referral

Joint cardiac–obstetric–

anaesthetic CDM team

Consulting with paediatric cardiologist,

endocrinologist, radiologist, HIV

specialist and others

Follow up with

maternity service

Postpartum referral to main cardiac

clinic, if indicated, for management

and possible cardiothoracic surgery

Abnormal

Normal

BMI: body mass index; ECG: electrocardiogram; ASD: atrial septal defect;

VSD: ventricular septal defect; EF: ejection fraction; NYHA FC: New York

Heart Association functional class; PPCM: peripartum cardiomyopathy;

HT: hypertension; AV: aortic valve

Fig. 2.

Referral algorithm for suspected and previously known

cardiovascular disease in maternity.