CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 1, January/February 2020

12

AFRICA

Statistical analysis

Since the survey did not capture where individuals sought care,

this analysis was limited to the rural population to minimise the

possibility of cross-contamination (study participants residing

near one facility but receiving treatment from another facility).

Because of the sparse distribution of healthcare facilities in

rural areas, the likelihood of individuals seeking care from a

healthcare facility other than their locally assigned facility was

believed to be lower. The analysis was restricted to individuals

residing near seven intervention facilities located in rural areas

and the seven matched control facilities. Due to difficulties in

matching intervention and control facilities supported by the

same implementation partner, select rural intervention facilities

were matched to control facilities located in more urban areas.

At baseline and end point, statistical differences between the

intervention and control groups with regard to demographics

and lifestyle characteristics were evaluated using a

t

-test for

bimodal variables and a chi-squared test for outcomes with more

than two values. The impact of HHA intervention, defined as the

treatment effect (TE) on hypertension awareness and knowledge,

BP screening and patient recall of provider recommendation was

assessed using a difference-in-differences (D-in-D) regression

analysis, which minimises bias due to other factors that change

over the same time frame.

Results

A total of 838 individuals were surveyed at baseline (intervention,

n

=

432; control,

n

=

406) and 698 at the end point (intervention,

n

=

364; control,

n

=

334). Demographics (age, geographic location

and education) were well balanced between the intervention and

control groups sampled at baseline and the end point (Table 2).

Nevertheless, the two treatment groups at both baseline and end

point varied with regard to wealth and lifestyle characteristics.

At both baseline and end point, individuals in the intervention

group were wealthier and tended to consume one or more

servings of fruit per day (

p

<

0.05 for all). In addition, at the end

point, a significantly greater proportion of individuals in the

intervention group consumed alcohol and one or more servings

of vegetables per day (

p

<

0.05 for both).

Hypertension awareness (defined as having heard of

hypertension) among the intervention group was high at baseline

(91.0%) and increased to 94.9% by the end point (Table 3). In

contrast, hypertension awareness was much lower at baseline in

the control group (79.1%) but had increased to 96.7% by the end

point. Of note, the D-in-D method’s underlying assumption of

parallel trends could not hold for this outcome, as an increase of

17 percentage points (pp) from an initial level of 91.0% was not

feasible in the intervention group.

Family and friends were the primary source of information

on hypertension for both the intervention and control groups at

baseline and the control group at the end point. However, by the

end point, a healthcare provider or facility became the primary

source of information for individuals in the intervention group

(TE, 19.4 pp;

p

<

0.05; Table 3).

In general, the intervention group experienced an increase in

knowledge of individual risk factors for hypertension. Significant

improvement was observed in individuals’ knowledge of tobacco

use as a risk factor for hypertension with intervention (TE, 4.0

pp;

p

<

0.05; Table 3). Within 12 months, individuals’ knowledge

of three or more hypertension risk factors also showed a trend

toward improvement in the intervention group [TE, 3.8 pp;

p

=

not significant (NS)].

A positive improvement in individuals’ knowledge of

hypertension management was seen in the intervention group.

Identification of alcohol reduction as a method for managing

hypertension significantly increased four-fold in the intervention

group (TE, 8.4 pp;

p

<

0.01). In addition, positive trends were seen

in the proportion of individuals who identified salt reduction as

a method for hypertension management (TE, 1.0 pp;

p

=

NS)

in the intervention group. Individuals’ knowledge of three or

more or five or more methods for managing hypertension also

improved three-fold (TE, 3.7 pp;

p

=

NS) and 17-fold (TE, 1.7

pp;

p

=

NS), respectively, in the intervention group.

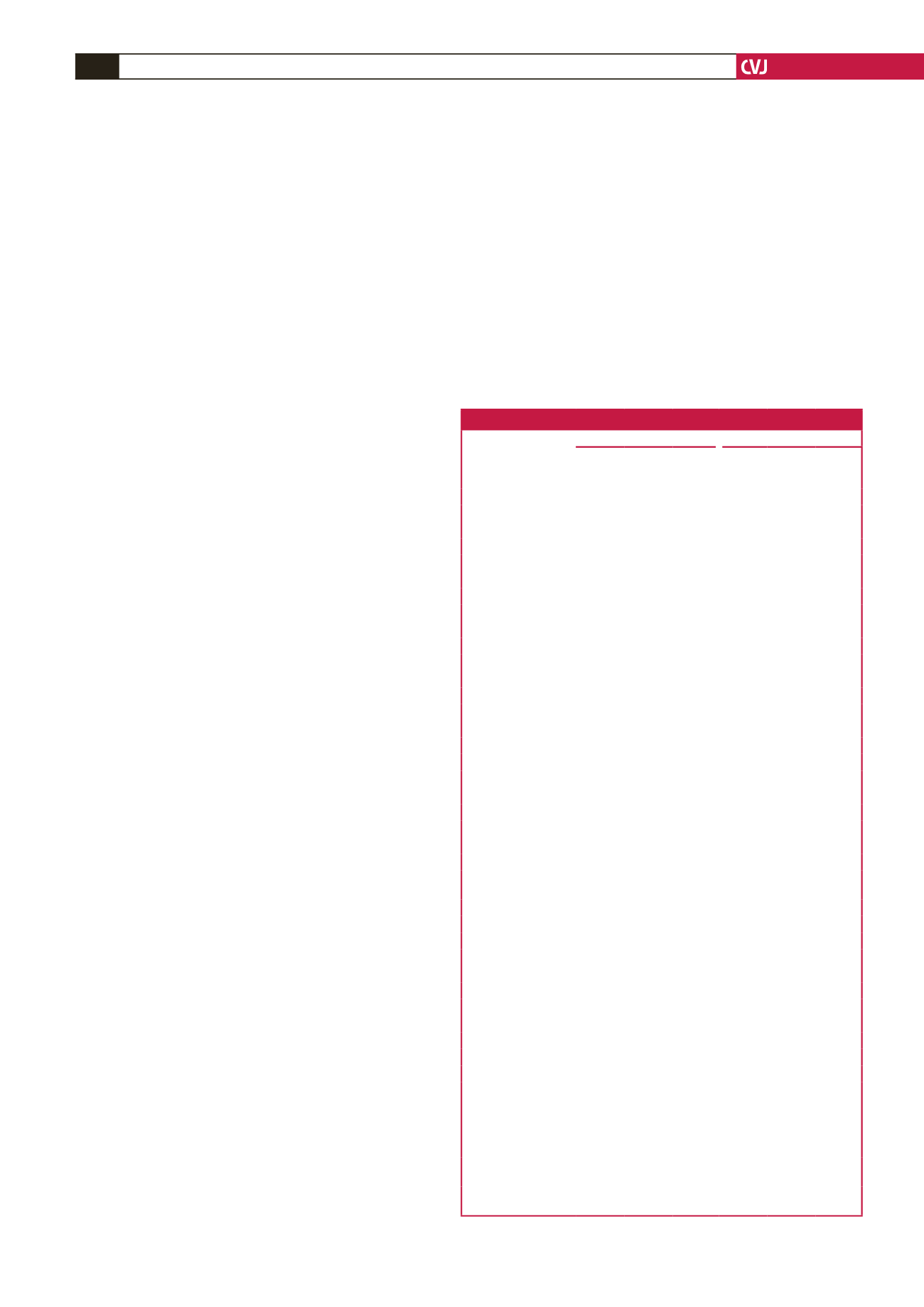

Table 2. Characteristics of survey respondents residing in rural areas

Baseline

End point

Interven-

tion

(

n

=

432)

Control

(

n

=

406)

p

-value

Interven-

tion

(

n

=

364)

Control

(

n

=

334)

p

-value

Geographic region, %

Central or eastern

63.6

63.6

0.345

75.0

72.4

0.175

Nairobi

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

Nyanza

10.1

0.0

9.8

0.0

Rift Valley

0.0

10.3

0.0

11.4

Western

26.4

26.1

15.3

16.2

Residence location, %

Rural

93.6

99.4

0.014*

69.3

99.5

0.000**

Urban

a

6.4

0.6

30.7

0.5

Age, years, %

18–24

18.7

20.0

0.647

22.4

14.3

0.128

25–29

12.7

8.9

14.2

16.0

30–34

10.9

12.3

14.0

10.8

35–39

11.2

13.3

9.3

7.6

40–44

11.2

8.7

11.6

9.7

45–49

6.6

6.9

7.0

8.8

≥

50

28.8

30.0

21.6

32.8

Gender, %

Male

48.7

46.0

0.269

50.6

55.7

0.448

Female

51.3

54.0

49.4

44.3

Education, %

Nursery/kindergarten 1.8

2.0

0.834

3.5

2.7

0.310

Primary

47.4

48.7

37.1

48.2

Post-primary,

vocational

4.1

3.5

4.3

5.3

Secondary, A-level

36.4

32.2

39.3

30.1

College (mid-level)

6.0

6.5

11.8

6.4

University

1.7

1.7

1.4

1.2

No school attended

2.5

4.8

2.5

6.0

Wealth quintile, shillings/month, %

≤ 653

34.3

33.5

0.000**

25.6

37.9

0.000**

654–2 158

17.2

13.6

22.4

20.6

2 159–2 633

25.8

51.6

15.4

38.8

2 634–3 631

21.2

0.5

32.4

1.0

≥

3 632

1.5

0.8

4.2

1.7

Lifestyle characteristics, %

Non-smoker

87.8

91.5 0.392

92.0

86.6 0.104

Does not drink

alcohol

78.0

82.8 0.177

80.2

87.4 0.023*

Consumes

≥

1 fruit

serving/day

52.0

26.3

0.001**

60.8

36.0

0.010*

Consumes

≥

1

vegetable serving/day

68.1

56.5

0.446

84.9

54.1

0.016*

*

p

<

0.05; **

p

<

0.01 vs control.

a

Select intervention facilities were matched to control facilities.