CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 1, January/February 2020

14

AFRICA

Individuals’ knowledge of hypertension-related consequences

remained relatively unchanged. This was expected to a

certain extent, as the programme intervention did not educate

healthcare providers or the general public on the consequences

of hypertension.

7

In addition, HHA intervention areas did not

have a significant change in the number of individuals screened

for BP or diagnosed with hypertension, emphasising the need

for more innovative outreach activities/approaches to identify

individuals at high risk for hypertension, including those who

may not necessarily visit healthcare facilities.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to

characterise and intervene to improve individuals’ awareness

and knowledge of hypertension among the rural population in

Kenya. Previous studies have reported a low degree of awareness

among Kenyans, but clinically meaningful comparisons were

not possible due to a lack of a standardised definition for

hypertension awareness.

2,5,6,11

However, a recent qualitative study based on a series of focus

group discussions with 53 individuals with HIV-1 conducted

at the Kenyatta National Referral and Teaching Hospital

Comprehensive Care Centre reported a gap between hypertension

awareness and knowledge, similar to what was seen in this study.

11

Respondents commonly referred to hypertension as ‘pressure’

and, although all of the participants had heard of the term,

most were unable to adequately describe it. Stress followed by

fatty foods, excessive salt intake, and physical inactivity were the

most frequently cited causes of hypertension. All respondents

demonstrated some knowledge regarding treatment modalities

for hypertension; however, most believed that hypertension could

not be prevented.

This gap between awareness and knowledge/understanding is

not strictly limited to hypertension and extends to individuals’

awareness and understanding of CVDs. A systematic review

evaluating awareness and knowledge of CVDs in sub-Saharan

Africa found that awareness, when reported, was high; however,

knowledge and understanding of CVDs and CVD risk factors

were poor.

12

Although limited, the data suggest that individuals

may benefit from intervention efforts designed to not only

raise awareness but also improve general understanding and

knowledge of hypertension. The HHA programme’s positive

impact on knowledge of hypertension may help to address

this critical gap in communication, and, when coupled with

the previously reported facility-level improvements in provider

education and ability to diagnose and treat hypertension,

7

may

lead to greater utilisation of hypertension services and, in turn,

timely diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.

There are some inherent limitations associated with this

analysis. The generalisability of the data is limited, in part, by

study design. This study was not designed to collect nationally

representative findings and therefore data interpretation is

limited to individuals residing near the study sites. In addition,

this study did not capture where respondents received care.

Potential ramifications of receiving care at distant sites were

mitigated by focusing on the rural population, which, due to

limited access to healthcare facilities, is more likely to receive

care at the local facility. The study design did not the capture

frequency and type of study- and non-study-related hypertension

awareness/education events conducted within the study area,

which may affect programme evaluation.

Furthermore, the short duration of this study may not be

sufficient for evaluating the impact of the HHA programme,

as significant changes in individuals’ behaviours and attitudes

towards hypertension care may require a longer period of

time in this setting. The impact of the HHA programme may

be underestimated as HHA-trained healthcare providers from

intervention facilities may have been moved and replaced with

untrained healthcare providers, a by-product of routine transfer

and the devolution of the Kenyan government,

8

which occurred

during the 12-month study period.

Conclusion

Little is known about how to rapidly improve control of

hypertension in low- to moderate-income countries. The results

from this study may help to develop more realistic expectations

on the anticipated rate of improvement in individuals’ awareness

and knowledge of hypertension and health-seeking behaviour

towards hypertension care. In this study, individuals residing

in rural Kenya demonstrated a high degree of hypertension

awareness; however, their medical knowledge of hypertension

was quite poor.

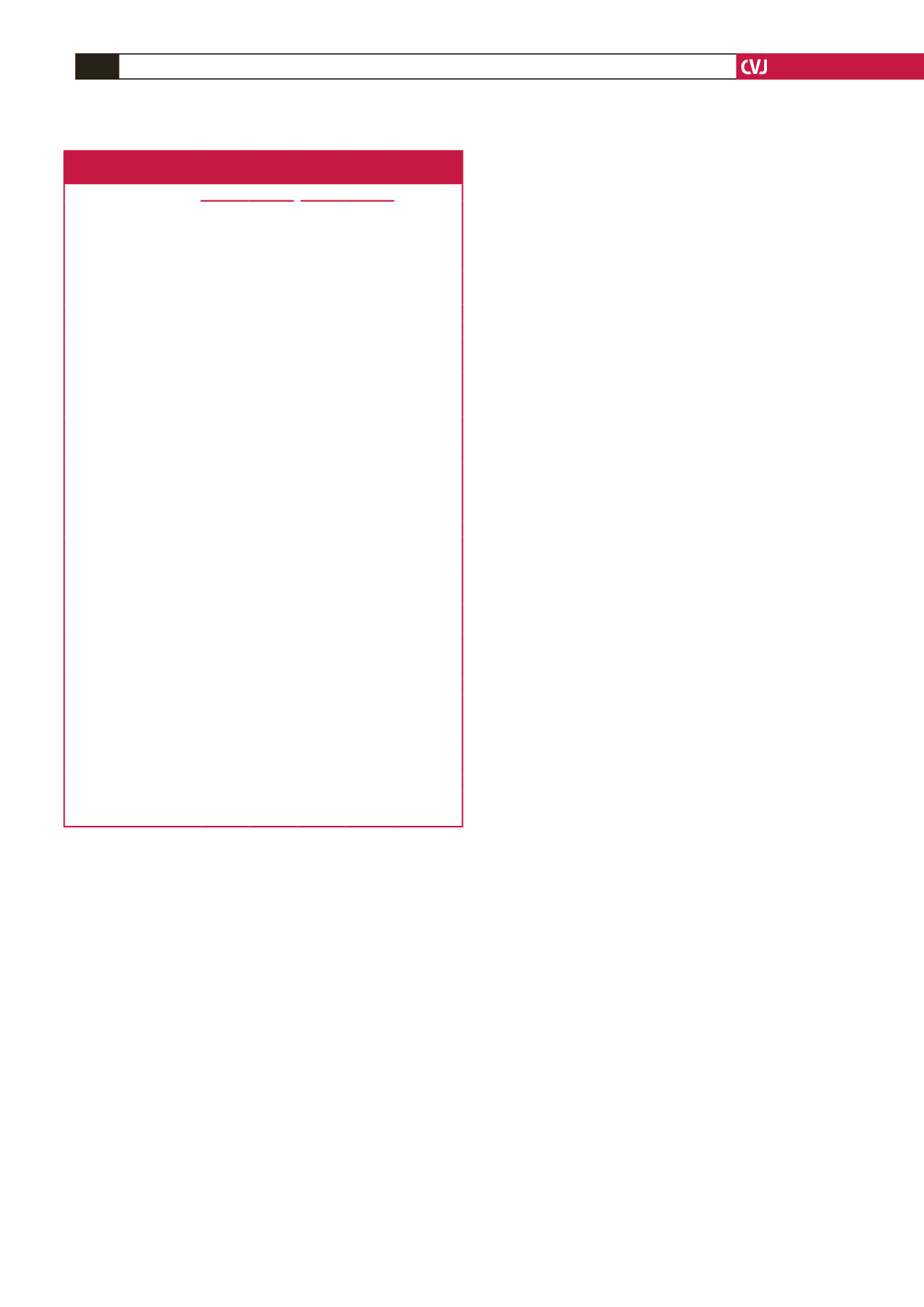

Table 4. Impact of Healthy Heart Africa on hypertension diagnosis and

provider’s recommendation

Baseline

End point

Treatment

effect (SE),

percentage

point

Interven-

tion

(

n

=

432)

Control

(

n

=

406)

Interven-

tion

(

n

=

364)

Control

(

n

=

334)

Individuals who reported

being screened for BP, % 74.3

62.6

72.9

77.6 –19.9 (7.8)*

Last time BP screening was performed, %

≤ 6 months

38.7

24.4

37.8

39.4 –15.2 (4.6)**

7–12 months

10.2

8.8

12.1

16.3

7.2 (4.8)

≥

12 months

24.8

27.8

22.2

21.9

0.7 (4.1)

BP screening location, %

Public hospital

29.3

29.0

27.1

19.9

8.3 (7.8)

Public health centre or

dispensary

40.9

24.1

35.9

44.6 –16.2 (9.0)

Private hospital

5.6

8.9

13.3

18.2 –2.7 (3.4)

Private health centre or

dispensary

11.3

6.1

15.5

13.7 –4.6 (6.4)

At screening event

1.2

0.8

2.5

8.1 –7.4 (2.9)

Other

7.7

10.4

15.0

21.1 –2.0 (1.6)

Individuals who reported

being diagnosed with

hypertension, %

14.9

8.8

12.9

10.3 –0.03 (3.3)

Timing of hypertension diagnosis, %

≤ 6 months

3.8

2.9

2.7

2.9 –1.2 (3.0)

7–12 months

2.1

1.0

3.8

1.3

2.5 (1.1)

>

12 months

8.8

4.9

5.5

5.1 –1.3 (2.7)

Individuals’ recall of healthcare providers’ recommendation, %

≥

1 healthcare providers’

recommendation

13.4

8.8

9.8

9.3 –2.3 (3.5)

≥

3 healthcare providers’

recommendations

0.1

2.1

0.5

1.4

1.2 (0.9)

Medication

13.1

7.1

7.2

8.2 –5.0 (2.5)

Reduction in salt

2.2

3.8

4.0

4.0

2.0 (1.6)

Lose weight

0.1

2.0

0.6

1.3

1.9 (1.7)

Reduce alcohol consump-

tion

0.2

0.7

0.6

0.0

1.3 (0.5)*

Exercise

1.4

2.3

1.3

1.3

1.3 (1.5)

Reduce stress

3.5

2.1

3.8

3.6

0.4 (1.3)

Home remedies

0.3

0.9

0.1

0.7

0.3 (0.7)

Unable to recall

0.9

0.1

1.6

0.6

0.8 (1.5)

*

p

<

0.05; **

p

<

0.01 vs control. BP: blood pressure; SE: standard error.