CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 1, January/February 2020

50

AFRICA

inactive. The African race had a lower prevalence compared with

the other races. Urban dwellers, and those who had a medical

aid, or engaged in no physical exercise, or had ever smoked, or

had ever used alcohol, or whose BP measurements were taken in

winter had hypertension prevalences higher than their respective

counterparts. Those who were higher in the income band had

prevalences significantly higher than those in the lower income

level.

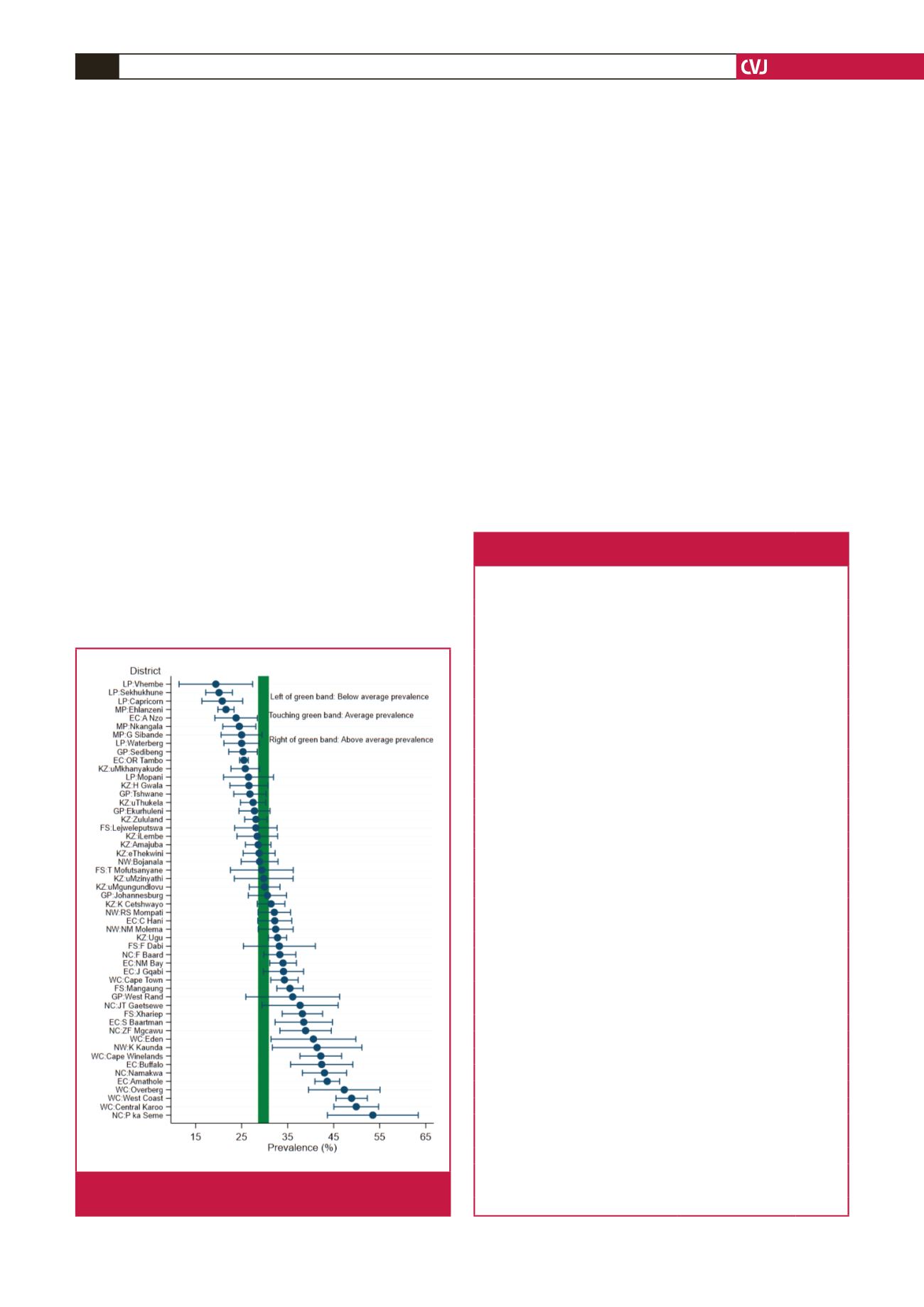

Fig. 1 shows the unadjusted weighted hypertension prevalence

and 95% CI for South African districts. The average national

prevalence was 29.8% (95% CI: 28.7–30.9%: green band).

Approximately eight districts showed a prevalence that was lower

than that of the national level, while about 16 districts showed a

prevalence that was significantly higher than that of the national

level. However these estimates are imprecise as characterised by

the large confidence intervals.

Except for A Nzo and OR Tambo (both in the Eastern Cape

Province), the districts with a lower-than-average prevalence

were found in the north-eastern provinces of Limpopo and

Mpumalanga. By contrast, the districts with a higher prevalence

than average were from the Western and Northern Cape

provinces. In between these two extremes lay the majority of

the districts whose prevalence was approximately equal to the

average. These districts were mostly found in KwaZulu-Natal,

Gauteng, parts of the Free State and Eastern Cape, and North

West provinces.

Factors associated with hypertension

: after accounting for other

factors, the greatest effect on hypertension was shown to

be basically from the demographic factors of age and race,

where the OR was approximately 5.5 times more for every five

years increase in age, while the Coloured and black African

populations, respectively, were about 2.5 and 1.5 times more

likely to be hypertensive compared with the combined races of

whites and Asians.

Other factors associated with hypertension prevalence were

BMI (OR

=

2.29,

p

=

0.001 for those with BMI at least 25.0

kg/m

2

), alcohol use (OR

=

1.25,

p

<

0.001), season (OR

=

1.33,

p

<

0.001 for winter vs autumn/spring) and residence (urban vs

traditional/farm, OR

=

1.12,

p

≤

0.011). Adjusted prevalence

was more likely to be lower for females compared with males

and decreased with level of education. Medical aid and smoking

status were not found to be significant predictors of hypertension

prevalence for these samples.

Hypertension variance

: Table 3 presents the distribution of

hypertension variance at the individual and district levels. Most

Fig. 1.

Design-based hypertension prevalence rates by

districts in South Africa.

Table 3. Fixed and random effects associated with

hypertension prevalence in South Africa

Factor

Odds ratio (95% CI) p-value

Period/year (vs 2008)

2010/11

0.72 (0.66–0.78)

0.000

2012

0.81 (0.75–0.88)

0.000

2014/15

0.75 (0.70–0.81)

0.000

2017

0.64 (0.59–0.70)

0.000

Gender (vs male)

Female

0.86 (0.80–0.92)

0.000

Age

1.11 (1.10–1.11)

0.000

Race (vs Asian/Caucasian)

African

1.52 (1.30–1.78)

0.000

Mixed race

2.56 (2.13–3.07)

0.000

Residency (vs traditional/farms)

Urban

1.12 (1.03–1.22)

0.011

Education level (vs pry and below)

High school

0.86 (0.80–0.93)

0.000

Certificate/diploma/Bachelors’+

0.76 (0.68–0.84)

0.000

Income tertile (vs low)

Medium

0.90 (0.85–0.96)

0.001

High

0.96 (0.89–1.03)

0.231

Employment status (vs employed)

Unemployed

0.97 (0.90–1.04)

0.375

Economically inactive

0.93 (0.87–0.99)

0.014

Has medical aid

1.01 (0.91–1.11)

0.861

BMI (vs

≤

normal weight)

Overweight/obesity (≥ 25 kg/m

2

)

2.29 (2.16–2.42)

0.000

Physical exercise (vs no exercise)

Some exercise

0.98 (0.92–1.03)

0.438

Alcohol use (vs never used)

Yes

1.25 (1.17–1.33)

0.000

Unknown

1.06 (0.93–1.20)

0.384

Smoking status (vs never smoked)

Ever smoked

1.00 (0.93–1.08)

0.920

Season (vs autumn/spring)

Summer

0.80 (0.76–0.85)

0.000

Winter

1.33 (1.26–1.40)

0.000

Random effects

District

0.11 (0.07–0.18)

Repeated observations

3.32 (3.13–3.51)