CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Volume 31, No 1, January/February 2020

52

AFRICA

distribution at the higher level (district), with a VPC of 3.8

and 2.1% for the null and the risk-factor-adjusted models,

respectively. After adjusting for the effect of risk factors, the

level-specific change in variance (Ds

2

) was equally important at

both the individual and district level.

This implies that the risk factors were unequally distributed

between individuals and between districts. This could possibly

be the reason for the difference in race-wise results between the

unadjusted and adjusted estimates. The unadjusted prevalence

showed that prevalence was highest inAsian/Caucasians, followed

by the mixed race, and lowest in Africans, while the adjusted

estimates showed lower chances of hypertension in Asians/

Caucasians. This most likely was due to the reduced confounding

effect of age, whose average was highest in Asians/Caucasians,

followed by the mixed race and lowest for Africans. A previous

study found age-standardised self-reported hypertension to be

highest in mixed-race women followed by African women.

39

There were important geographic variations in hypertension

prevalence between districts in South Africa, even after

controlling for socio-demographic and behavioural background

factors. Districts with a lower-than-average prevalence were

mostly in the north-eastern part of the country (Limpopo,

Mpumalanga and Gauteng provinces) while those with a higher-

than-average prevalence were mostly found in the Western,

Eastern and Northern Cape provinces. Most of these districts

are coastal districts in close vicinity to the Atlantic Ocean. A

previous study that limited geographic variation of hypertension

to the provincial level found similar clustering of hypertension

prevalence.

22

Identifying districts (sub-units) with high and low

hypertension prevalence could be useful in programming

public health interventions. Districts with a high hypertension

burden could be considered for targeted prevention and control

programmes, rather than one national intervention programme.

As governments, especially in LMICs, are faced with multiple

needs and limited resources, their role of ensuring that all people

have equitable access to preventative, curative and rehabilitative

health services involves preventing them from developing

hypertension and its complications.

40-42

Our study has shown

that, although the majority of South African districts had

approximately the same burden of hypertension, some had

a heavier burden than others, even after accounting for risk

factors documented to have a strong influence on hypertension

prevalence.

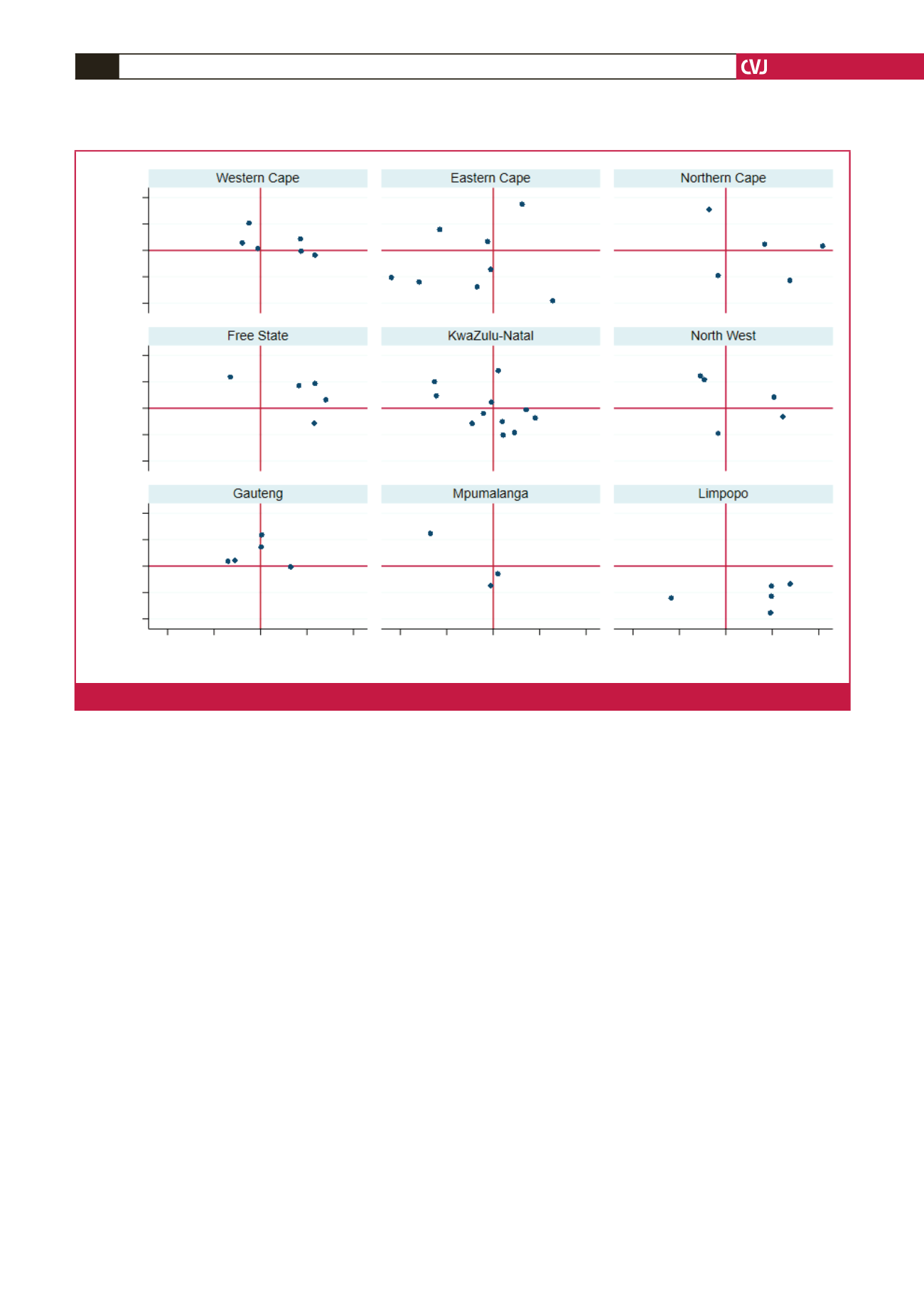

The effects of age and BMI on hypertension prevalence were

found to vary from district to district, showing their slopes were

higher in some districts relative to others. Health services that

address the risks of hypertension, for example body mass, should

target such areas.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge this is the only study to have

estimated the prevalence of hypertension at the district level,

Random slopes: BMI (district)

0.02

0.01

0

–0.01

–0.02

0.02

0.01

0

–0.01

–0.02

0.02

0.01

0

–0.01

–0.02

Random slope: age (district)

0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08

0.1 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08

0.1 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08

0.1

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot for districts’ random slopes for age and BMI.