CARDIOVASCULAR JOURNAL OF AFRICA • Vol 21, No 3, May/June 2010

156

AFRICA

tricuspid insufficiency, ejection fraction of 40 to 45% and 36

mmHg pulmonary artery pressure. No thrombus was detected

in any cavity.

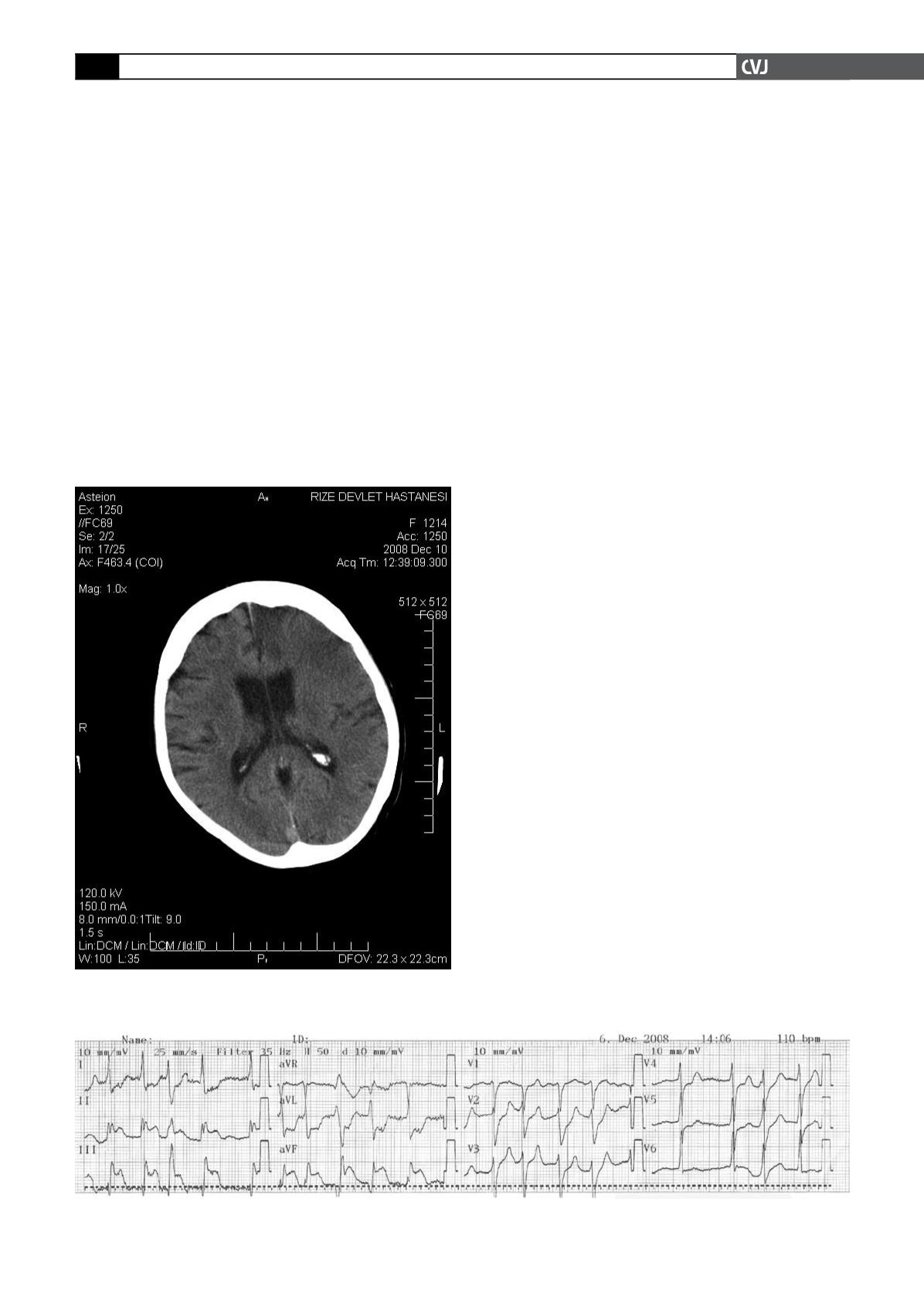

The patient had deteriorated after two hours of intravenous

TT. Motor aphasia and right hemiparesis then developed. The

Babinski sign was positive in the right lower extremity. Immediate

cerebral tomography (CT) was performed and showed no patho-

logical abnormality. The patient then consulted a neurologist. In

the second CT 12 hours later, extensive infarction of the left fron-

tal area was seen (Fig. 2). On the follow up, neurological deficits

had increased, congestive heart failure developed, and finally the

patient died on the ninth day following TT.

Discussion

STEMI is an urgent condition caused by acute thrombotic occlu-

sion of the coronary arteries. Angiographic studies have shown

that coronary arterial thrombosis is present in about 85% of

patients with STEMI.

6

The most important therapeutic method is

immediate recanalisation of the infarct-related coronary artery.

There are two methods to do this, PCI or a pharmacological

approach.

PCI is the more favourable approach, but it presents many

technical and scientific limitations. In our case, because of the

respiratory insufficiency, the patient could not lie down so we

could not do PCI. We decided to carry out intravenous TT with

streptokinase because of its lower incidence of cerebral haemor-

rhage.

TT is an effective and easy therapeutic method that can be

used anywhere and at any time. As in all therapeutic options,

TT has certain limitations and complications. The most impor-

tant and feared complication of a fibrinolytic agent is bleeding,

especially intracranial bleeding. It occurs in 0.9% of patients

treated with tPA.

5

Bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment is due

to the depletion of clotting factors and lysis of recently formed

haemostatic plugs.

7

TT for STEMI has reduced mortality at the expense of

additional intracranial haemorrhage. The proof of efficacy of

thrombolysis for STEMI comes from nine randomised placebo-

controlled trials in a total of 58 511 patients. The meta-analysis

of these trials showed an overall survival advantage of about 2%

(11.5 vs 9.6%) in favour of thrombolysis.

7

A meta-analysis of

randomised trials comparing PCI with thrombolytics for STEMI

at high-volume hospitals suggested that PCI improved 30-day

survival free of reinfarction (11.9 vs 7.2%). Stroke risk was also

reduced with PCI compared with thrombolytic therapy.

8

Two randomised trials compared low-molecular weight

heparin (LMWH), enoxaparin, with unfractionated heparin in

patients with UA or non-STEMI.

9,10

All patients received aspirin.

In both studies, there were reductions in short-term outcomes

of death, myocardial infarction (MI) and recurrent angina in

patients randomised to LMWH. A combined analysis of these

two trials showed significant 20% reductions in the short-term

risk of death and non-fatal MI in patients randomised to LMWH.

Randomised trials in STEMI patients conducted in the pre-fibrin-

olytic era showed that the risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke

and re-infarction was reduced in patients who received intrave-

nous heparin, providing support for the prescription of heparin to

STEMI patients not treated with fibrinolytic therapy.

With the introduction of fibrinolytic therapy and, importantly,

after the publication of the ISIS-2 trial,

3

the situation became

more complicated because of strong evidence of a substan-

tial mortality reduction with aspirin alone, and confusing and

conflicting data regarding the risk–benefit ratio of heparin used

as an adjunct to aspirin or in combination with aspirin and a

fibrinolytic agent. For every 1 000 patients treated with heparin

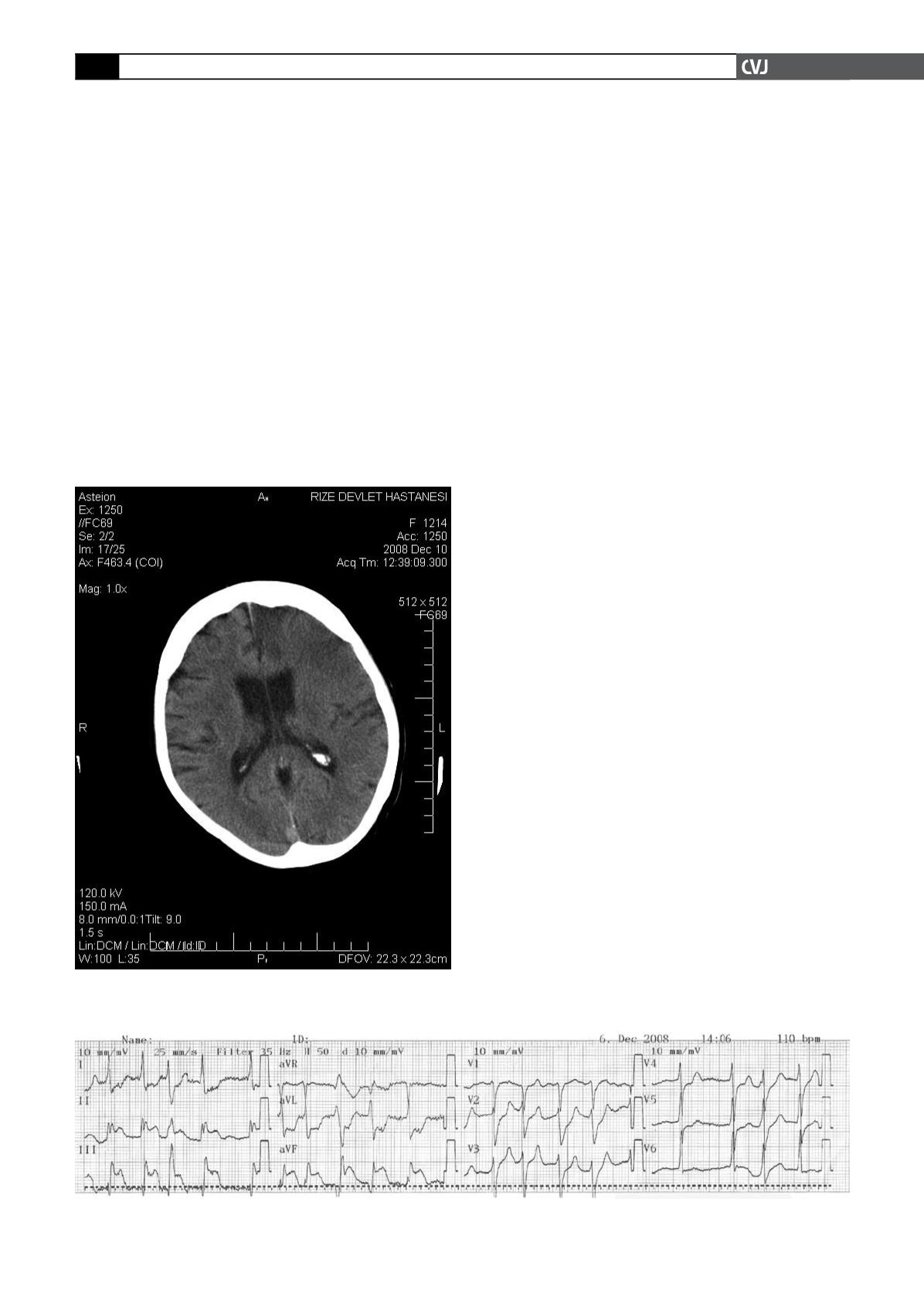

Fig. 1. Electrocardiography showing atrial fibrillation and

ST-segment elevation in leads D2, D3 and AVF.

Fig. 2. The second CT, 12 hours later, showing extensive infarction of the left frontal area.